Our News, Your News

By Dylan Levi King, October 19, '20

In China in Ten Words, Yu Hua describes stubbing his toe on stacks of Lu Xun books gathering dust in the office of a provincial cultural center and saying to himself, "'That guy's days are over, thank goodness!'" (this is from the translation by Allan H. Barr).

As Yu Hua puts it, Lu Xun went "from being an author to being a catchphrase and then back again." Lu Xun’s legacy was flattened in the long half-century after his death. When state control over literature loosened on both sides of the Straits in the ‘80s, attempts were made to reinflate the flattened Lu Xun, but perhaps the damage was already done.

What changed Yu Hua’s mind was picking up the collected short fiction after a director pitched him on writing a script based on some of Lu Xun’s stories.

It made me think back to those books of his under the table in the cultural center, and it seemed to me now that they had been trying to tell me something. When they tripped me up as I went in and out of my office, they were actually dropping a hint, quietly but insistently signaling the presence of a powerful voice within the dusty tomes.

I always found the veneration of Lu Xun understandable, and I appreciate his contributions to contemporary Chinese literature, but I found it hard to see much vital and pressing in his work. Matt Turner’s translation of Lu Xun’s Weeds was a minor revelation last year.

More…

Toward the end of every year, when China’s magazines, newspapers, and online portals publish their lists of the best books of the year, we are reminded of the vast gulf between the books that are being read in China and the books being translated from Chinese for readers around the world.....

Thu, 22 October 2020, 19:00 – 20:15 British Summer Time

We'll discuss our (wildly!) different translations of an excerpt from a short story by Shen Dacheng (沈大成) from her 2020 collection entitled Asteroids in the Afternoon (小行星掉在下午), published by Imaginist Press. The excerpt and the translations will be made available prior to the event. It doesn't matter if you don't know a word of Chinese....You can still expect some great online entertainment.

By Nicky Harman, October 13, '20

Most readers nowadays, asked to name a contemporary Chinese writer, could manage at least one. But the odds are that it will be a man. In these interviews, we explore how Chinese women authors from mainland China see themselves and their status.

In recent decades in mainland China, there have been vast improvements in standards of living and personal freedoms (to choose one's higher education and career, and to travel, for instance) and a small number of women writers have flourished. For instance, the current head of the China Writers Association, Tie Ning, is a woman. However, women writers still appear to lag far behind their male counterparts in other respects. Only nine of forty-three winners of the Mao Dun Literary Prize were women between 1982 and 2015; as were only twenty-seven of 228 Lu Xun Prize awards (various categories) between 1995 and 2017. And far fewer women are translated into English: of 117 novels translated from Chinese between 2012 and 2018, only thirty-five were by women. Our aim in translating and publishing these interviews is to bring the opinions of Chinese women writers on this topic, in all their variety and complexity, to English-language readers.

Notes: With the exception of Wang Bang, all writers answered in Chinese. The initials of the translator can be found at the end of each interview. Some writers chose to remain anonymous. We have published the response of another writer, Tang Fei, separately. It can be read in Words Without Borders.

Nicky Harman and Natascha Bruce

More…

Every year the International Youth Library, in Munich, selects outstanding new children's books from around the world for its annual White Ravens catalogue, published in time for the Frankfurt Book Fair (Nov). This year, 200 titles were selected in 36 languages from 56 countries, including EIGHT written in Chinese. The blog also includes a link to a newly created list of the 139 Chinese White Ravens since 1984.

By Bruce Humes, October 1, '20

At the same time that it lays bare the ground that shaped this particular family, “Bestiary” also paints a portrait of Taiwanese identity, poking at the various histories and horrors that built the island and its citizens. A place where “Ma doesn’t measure her life in years but in languages: Tayal and Yilan Creole in the indigo fields where she was born … Japanese during the war, Mandarin in the Nationalist-eaten city. Each language worn outside her body, clasped around her throat like a collar.” From pirates to soldiers and those who came before, the men who claimed Taiwan and the women who sustained it, the country’s evolution is as much a part of the book’s collection of beasts as is the tiger spirit.

2020 has been a whirlwind year, and it would have been a special year to celebrate the Shanghai-born Chinese American writer Eileen Chang, as her name rhymes with “two-zero” in Mandarin. English readers may have heard of her through Ang Lee’s 2007 film adaption of her novella, Lust, Caution, but her life, her body of work, her influence, and her status in Chinese twentieth-century literature, surpass the scandalous nature of the NC17-rated spy thriller set in 1940s Shanghai.

To celebrate her revered literary genius and her acute observation of all walks of life, Asia Society Museum presents a monthlong celebration with a list of recommendations for you to “choose your own adventure.” This literary and cinematic journey will culminate at the end of September, the eve of Chang’s 100th birthday, with a conversation featuring scholars of twentieth-century Chinese literature, history, and culture.

"Paper Republic has grown and changed almost beyond recognition... But one thing has not changed: our enthusiasm for promoting Chinese literature in translation."

By Bruce Humes, September 17, '20

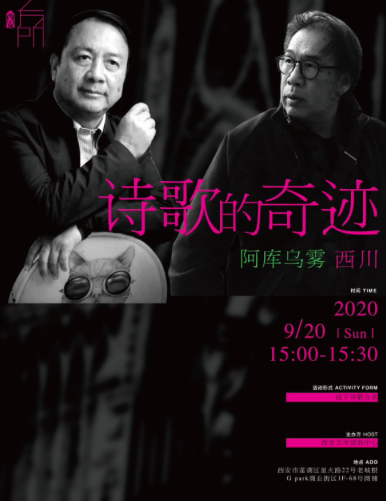

To celebrate its opening in Xi’an, Fangsuo Xi’an Creative Union (西安方所创联中心) will host a month or so of cultural forums/salons during mid-September to mid-October.

Poets Aku Wuwu (阿库乌雾) and Xichuan (西川) will appear together Sunday Sep 19 at 15:00-15:30, and Aku Wuwu will recite his long poem 《火颂》in the Yi language. Renowned Shaanxi novelist Jia Pingwa (贾平凹) is scheduled for some time during 16:00-18:00, if I interpret the poster correctly . . .

Venue: 西安市 莲湖区 星火路 22 号 老城根

G-Park 商业街区 1-F 68 商铺

For more on all the events during Sep-Oct info in Chinese visit here.

If that link downloads too slowly, you can try this one, but both are slow due to heavy load of graphics.

10 translated novels have been long-listed for the 2020 French-language Prix de littérature Émile Guimet. They include 3 by China-based authors :

Tempête rouge by Tsering Dondrup (from the Tibetan, translated by Françoise Robin)

Funérailles molles by Fang Fang (from the Chinese, translated by Brigitte Duzan)

Un parfum de corruption by Liu Zhenyun (from the Chinese, translated by Geneviève Imbot-Bichet)

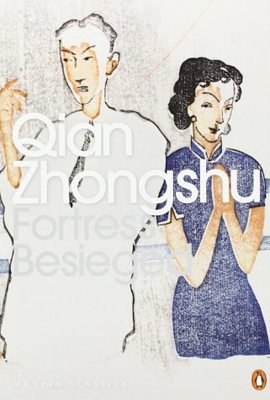

The metaphor (from the French “Le mariage est comme une forteresse assiégée; ceux qui sont dehors veulent y entrer, et ceux qui sont dedans veulent en sortir“) functions on many levels. In Qian’s satire, Fang finds disillusionment and disappointment in wartime Shanghai (full of frauds, phonies, and toadies), the relatively safe interior (where an innkeeper attempts to convince him and his traveling companions that maggots on their dinner are merely “meat sprouts”), the security of an academic career (Sanlü University proves to be a hotbed of petty intrigues), and the prestige of an international education. The image of a fortress under siege also applies to China itself: Fang and his compatriots return to Shanghai just in time to catch the Japanese invasion, and although Qian was much too subtle a writer to foreground the war and occupation – Fang leaves Shanghai to escape a broken heart, not the Japanese – they are a constant presence throughout the novel.

By Helen Wang, September 14, '20

A Century of Chinese Literature in Translation (1919–2019) English Publication and Reception

by Leah Gerber and Qi Lintao, published by Routledge, Sept 2020. ISBN 9780367321291

"Contributors from all around the world approach this theme from various angles, providing an overview of translation phenomena at key historical moments, identifying the trends of translation and publication, uncovering the translation history of important works, elucidating the relationship between translators and other agents, articulating the interaction between texts and readers and disclosing the nature of literary migration from Chinese into English."

More…

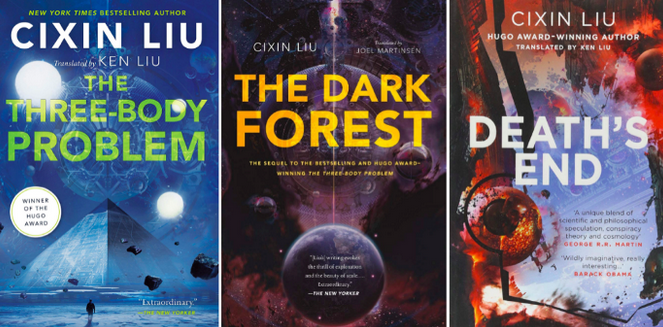

When I brought up the mass internment of Muslim Uighurs — around a million are now in reëducation camps in the northwestern province of Xinjiang — he trotted out the familiar arguments of government-controlled media: “Would you rather that they be hacking away at bodies at train stations and schools in terrorist attacks? If anything, the government is helping their economy and trying to lift them out of poverty.”

The answer duplicated government propaganda so exactly that I couldn’t help asking Liu if he ever thought he might have been brainwashed. “I know what you are thinking,” he told me with weary clarity. “What about individual liberty and freedom of governance?” He sighed, as if exhausted by a debate going on in his head. “But that’s not what Chinese people care about. For ordinary folks, it’s the cost of health care, real-estate prices, their children’s education. Not democracy.”

In a time of pandemic, what is the role of literature, particularly the form of online diary—the daily-based documentary genre that first appears on social media and is then translated into foreign languages and published in print abroad? Must the translator bear the burden of xenophobia from the nation of the source language?

By Dylan Levi King, August 2, '20

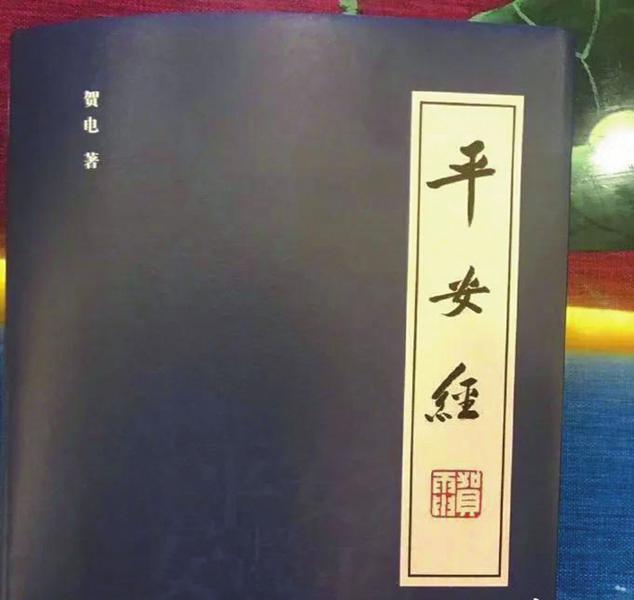

The biggest story in Chinese literature this week is a book called Peace Mantra (or Peace Sutra, Classic of Peace—however you want to translate Ping’an Jing 平安经), written by He Dian 贺电, an officer with the Public Security Bureau in Jilin.

The South China Morning Post's Liu Zhen describes Peace Mantra like this: “The 336 pages of the book are covered only with variations of the sentence: ‘Let … be safe.’”

Let the train stations of China be safe

Let Beijing Station be safe, let Xi'an Station be safe, let Zhengzhou East Station be safe, let Shanghai Hongqiao Station be safe, let Hangzhou East Station be safe, let Guangzhou South Station be safe, let Nanjing South Station be safe, let Chengdu East Station be safe, let Beijing South Station be safe, let Tianjin West Station be safe, let Wuhan Station be safe, let West Kowloon Station be safe, let Hsinchu Station be safe.

An introduction explains: “The world needs peace. The nation needs stability. All industries require safety. The people yearn for tranquility.”

When news of the book and He Dian’s extensive promotion spread to social media, it was mocked and condemned. State media joined in with editorials.

It seems clear that there was some funny business. The book was priced at 299 RMB ($42 USD), which doesn’t sound that bad, but puts it at a price point about six or seven times what most books sell for. There were symposiums held to discuss it, and there were public readings.

More…

By Bruce Humes, August 1, '20

A few years back I posted a piece entitled A Resounding “Yes” to Mother-tongue Literature — but for Whom and about What?

(Caption: Tempête rouge --- an example of a novel translated direct from the Tibetan)

In this context, “mother-tongue” referred to indigenous languages other than Mandarin. This topic may be of interest to Paper Republicans who perceive “Chinese literature” as encompassing writing in Tibetan, Uyghur, Mongolian, as well as oral literature (口述文学) for peoples who do not have a script widely used in the PRC, such as the Evenki, Zhuang and many others.

In my essay, I posed this question: Who is going to write in their native language — or read what is written for that matter — if they cannot receive a decent education in it?

For full text --- including update on China's "bilingual" education policy in Inner Mongolia, Tibetan regions and Xinjiang -- visit here.

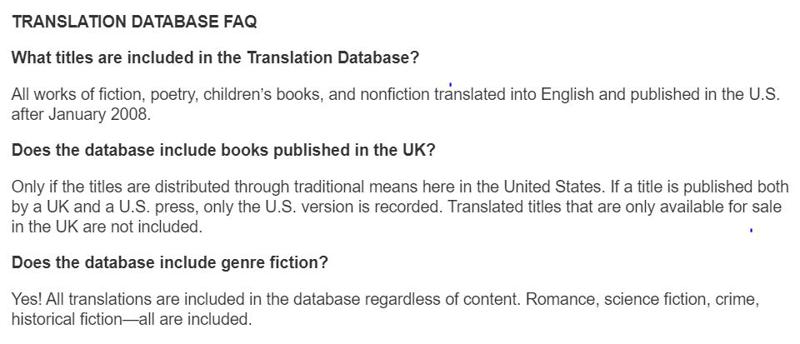

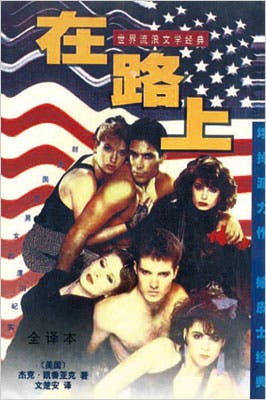

The only resource of its kind, the Translation Database was founded in 2008 by Three Percent and Open Letter Books at the University of Rochester to track all original publications of fiction and poetry published in the U.S. in English translation. With more than ten years of data, it is a robust tool for identifying what books are available, from which countries and languages, published by which publishers, and more. With the goal of determining what new voices were being made available to English readers, the database excludes all retranslations of previously published books, giving readers and researchers a clearer sense of what contemporary voices are making their way into English.

If there are titles missing from the database that are eligible for inclusion (never appeared in English in any form, distributed through conventional means in the U.S., published on or after January 1, 2008), please enter them using the form below. Also feel free to contact us with any corrections at Chad.Post@rochester.edu.

Search the Translation Database

Enter a New or Missing Title

Translation Database FAQs

By Jack Hargreaves, July 19, '20

For the final week of Sunday Sentence round one, we have the opening sentence of the as-yet untranslated 《六人晚餐》 (Dinner for Six) by Lu Min 鲁敏 (2012). Thanks to Emily Jones for the suggestion!

Please input your translation in the comments box at the bottom of the page.

The sentence to translate is:

所有的一切,不如就从厂区的空气说起。这空气,是酿造情感起源的酵母,也是腌制往事的色素与防腐剂。

Remember, you can post your translation anytime between now and next Sunday, so you have plenty of time to ponder and refine it.

More…

‘I’m a Chinese writer, I write about this place and I don’t wish to go elsewhere,’ says Murong Xuecun [慕容雪村].

Picture: Harvey Thomlinson, his translator

Free access.

Contains Scholar List of academics who conduct related research and translation, and links that often include their e-mail addresses.

By Dylan Levi King, July 13, '20

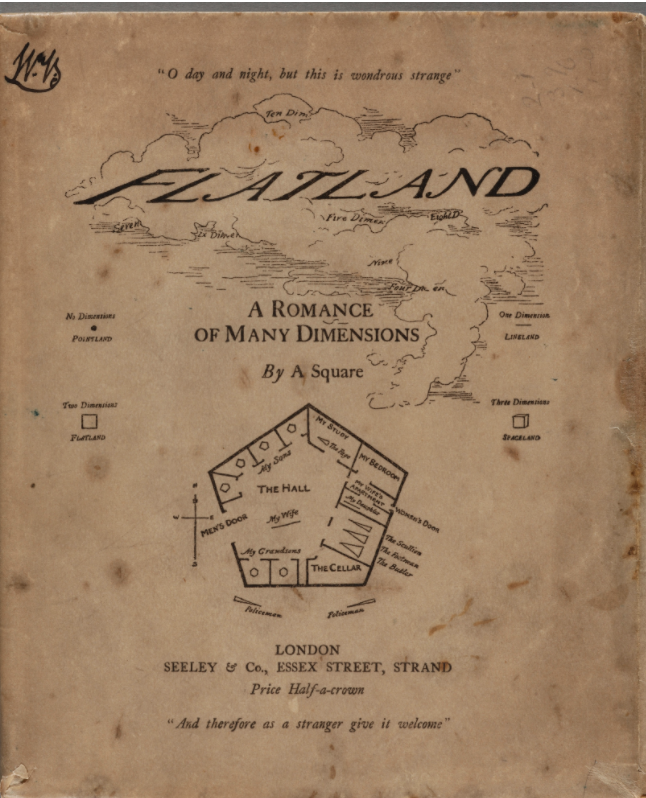

"Sinophiles between Flatland, Fetish, and Feuilleton":

Despite (or because of) the increasingly fraught relationship between the Chinese- and English-speaking parts of the world, to my eyes anglophone Chinese studies today finds itself blessed with a wealth of voices, both within academia and without. Projects like the ever-excellent Chinese Storytellers newsletter, for example, highlight the all too often overlooked contributions of Chinese and Chinese American journalists to the political and social discourse; Reading the China Dream fills out the picture with an angle on the intellectuals; Neil Clarke and his merry band of pranksters over at Clarkesworld continue to bring much needed attention to Chinese science fiction (in addition to that of other languages); or Paper Republic (as of last year, a registered charity in the UK!) and the Leeds Centre for New Chinese Writing, which do the same for Chinese language fiction more broadly.

By Dylan Levi King, July 12, '20

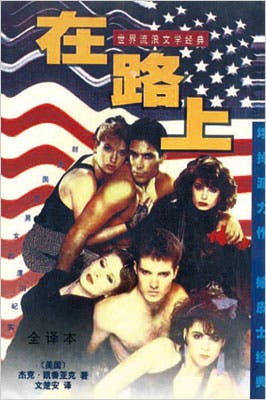

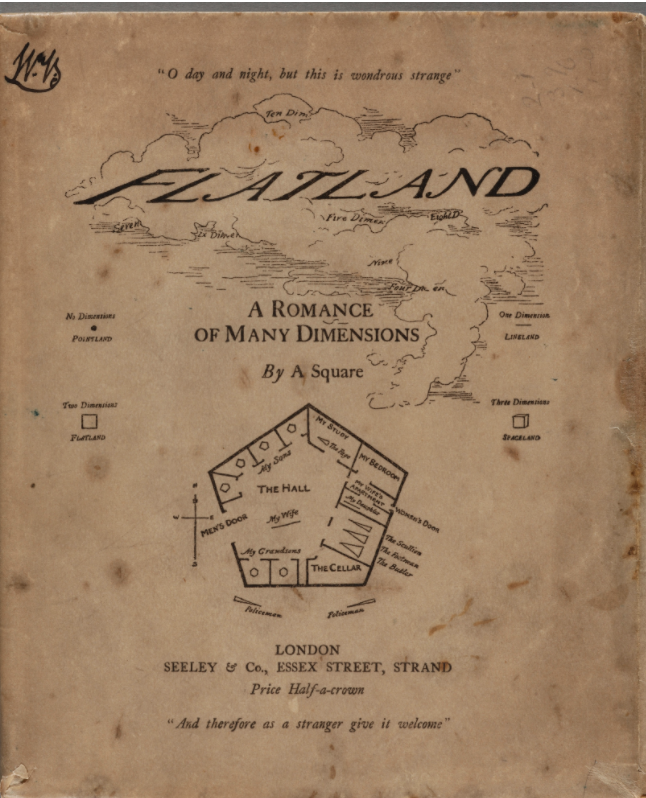

A short time ago, the Paper 澎湃 ran an interview with Tao Yueqing 陶跃庆 about his work on On the Road, in which he explains what it teaches us about America, the afterlives of the book, and how gave up on translation for a day job. (《在路上》译者陶跃庆:凯鲁亚克及其燃烧的时代.)

I’ll admit, I am jealous sometimes of our Chinese comrades. I understand it’s not glamorous work (it’s my job!), but a book like On the Road is not waiting out there for me—a book the publisher has to hustle to get it into a second, third, fourth printing, a book appearing in the rucksacks of disaffected urbanites for the next two decades, a book that I will be interviewed about thirty years later...

Tao Yueqing had no idea that he had just helped launch an American classic in Chinese translation. He took his half of the manuscript fee and went on with the rest of his life.

More…