Recent Projects

Our News, Your News

Human Translation in the Age of AI

By Nicky Harman, February 23, '26

Jack Hargreaves and I were part of this panel, held at Lancaster University and online, on this key topic.

2025 in books, according to China's official media coldwindow.substack.com

The most frequently recurring titles from over 20 book lists from cultural departments, (state-affiliated) magazines, and publishing industry blogs.

Thanks to Andrew, Cold Winter Newsletter, 22 Feb 2026

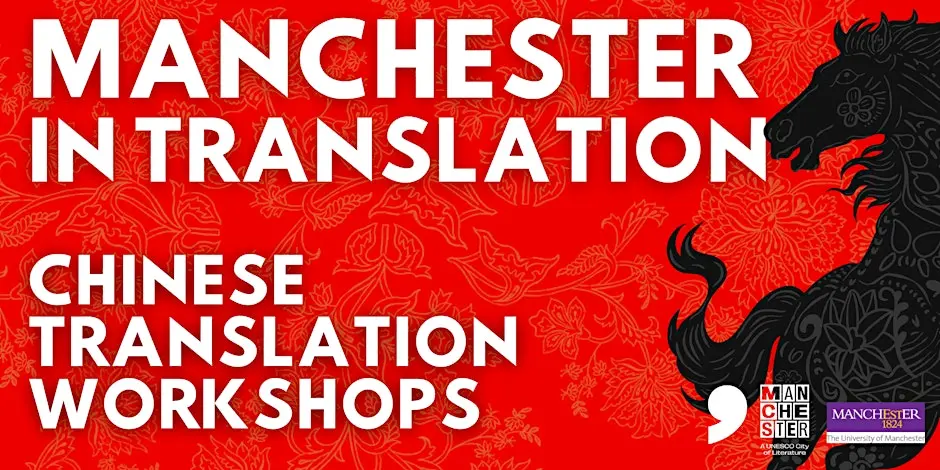

Manchester in Translation 2026 www.eventbrite.co.uk

Two translation workshops are taking place on Monday 23rd February in Manchester, UK @ Manchester Academy. Chinese-to-English led by Jack Hargreaves and English-to-Chinese led by Yu Kit Cheung.

For more details, see the link.

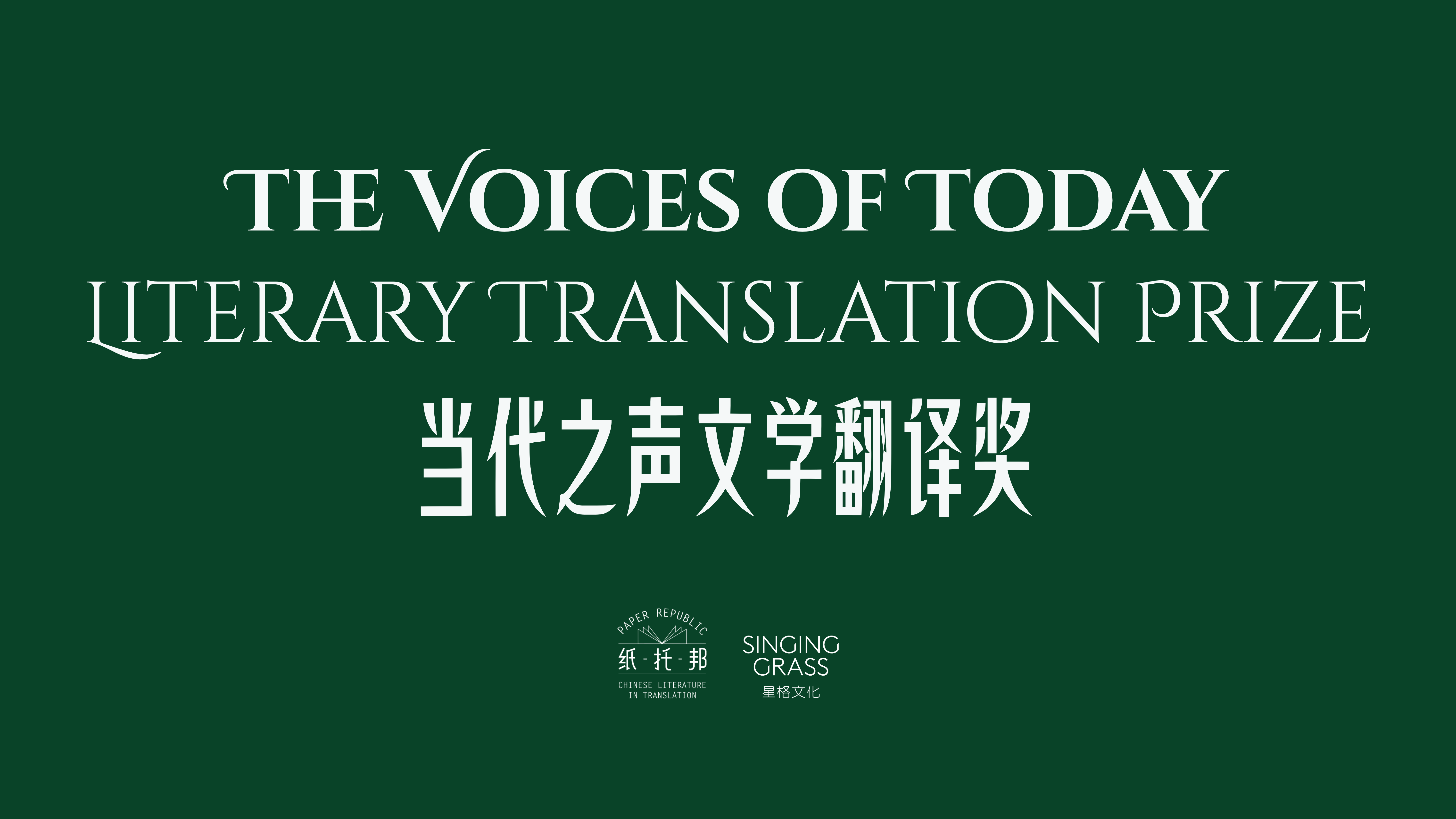

Launch of: THE VOICES OF TODAY LITERARY TRANSLATION PRIZE: CHINESE-ENGLISH LITERARY TRANSLATION WITH PAPER REPUBLIC

By Yao Lirong, February 14, '26

Singing Grass and Paper Republic are delighted to announce a new prize for translated fiction from Chinese to English designed to showcase literary translators of contemporary voices. This exciting initiative will invite participants to translate a short extract from the acclaimed Mao Dun prize-winning author, Liu Zhenyun whose new novel: Salty Jokes has just taken China by storm. The winning translator will receive £1500 and 2 runners-up £500 each. The submissions will be judged by an international Jury of translation experts.

Paper Republic Newsletter 25: Thawing Into Spring

By Yao Lirong, February 9, '26

We’ve been busy! In the last two months, we released two new Read Paper Republic collections. Highlights include 'Four Nanjing Poets' (a collaboration with Manchester City of Literature) and a special showcase of Taiwanese poets curated by Nero Huang. Explore the full series here.

As the Chinese New Year draws to a close, it’s a perfect time to look back at our 2025 Roll Calls for Chinese literature in English translation. A special thanks to Andrew Rule—thanks to his hard work, this year’s lists are more vibrant and visually engaging than ever.

In the meantime, we are making a final push for our community survey! We’ll be wrapping things up in mid-February, so please take a moment to share your thoughts. Your input is essential as we work to enhance Paper Republic in 2026.

Yang Hao in Conversation: Writing, Translation, and the Changing World. Video and transcript

By Nicky Harman, February 1, '26

On 15 October 2025, Trinity Centre for Literary and Cultural Translation hosted a dialogue with Yang Hao, described by The Irish Times as a new voice of Chinese literature. Joined by Irish writer Mark O’Connell, translators Nicky Harman and Michael Day—co-translators of Yang’s Diablo’s Boys. The talk explored how Diablo’s Boys《男孩们》 and The Long Slumber……《大眠》 (several stories from which have just been translated into English) blend virtual and real worlds to break realist boundaries with their "lyrical age" core. The translators shared efforts to preserve Yang’s poetic, labyrinthine prose and narrative ambiguity, while the writers debated stereotypes of Asian literature, advocating for literature to transcend identity and political labels and return to its literary essence.

For the video of the evening's event, click here

To read the transcript of the conversation, click

Dissecting the Douban Best Books of 2025 lists coldwindow.substack.com

"While Douban is by no means representative of all of China, it’s pretty representative of China’s young intellectual class. And in a country with almost no major independent literary prizes or dedicated book review venues, that makes Douban’s annual Best Books of the Year lists a pretty big deal."

- Top books: good year for literary memoir, dismal year for fiction

- Fiction: strong feminist representation in a weak year

- Rapid fire: the rest of the lists

Thanks to Andrew, Cold Winter Newsletter, 18 Dec 2025

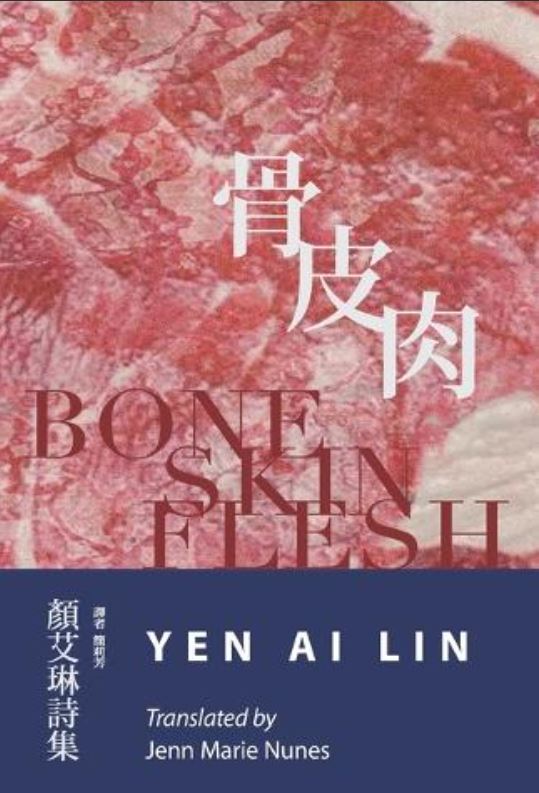

Yen Ai-Lin on Bone Skin Flesh www.soas.ac.uk

Event at SOAS, London, on 2 February 2026 - Bone Skin Flesh is the landmark work of Taiwanese poet Yen Ai-Lin. First published in 1997, it drew wide attention for its candid exploration of femininity and its groundbreaking series of erotic poems, making Yen the first female poet in Taiwan to publish such a body of work. Her poetry delves into gender and desire, leaving a lasting impact on readers and contemporary literary discourse. -- Translation by Jenn Marie Nunes (Balestier Press, 2025)

Twenty translators and a typhoon www.newwriting.net

About the ‘Symphony of Island and Literature’ translation workshop at the National Museum of Taiwan Literature (NMTL) in November 2025 - report by Anna Goode

Cold Window Newsletter #11: The best Chinese short fiction of 2025

By Andrew Rule, January 9, '26

Welcome back to the Cold Window Newsletter. I’ve always wished that someone would write an English guide to the best Chinese writing of the year. Now, I get to be the one to do it. Since the beginning of last year, I’ve been on a quest to read every new short fiction collection published in China in 2025. I’m finished, and I’m ready to share.

2025 Roll Calls of Chinese Literature in English Translation

By Andrew Rule, January 5, '26

2025 Roll Call of Chinese Children's Literature in English Translation

By Andrew Rule, January 4, '26

To wrap up our year-end translation roll calls, here's a list of Chinese children's literature translated into English in 2025. As always, if you notice a publication missing, please do let us know so we can add it. And if you are one of the authors or translators listed below but don't yet have a Paper Republic profile page, send us an email. We're always looking to add new profiles so that our translation database stays as complete and up-to-date as possible.

2025 Roll Call of Chinese Prose in English Translation

By Andrew Rule, December 23, '25

The year-end roll calls continue with lists of all the fiction and nonfiction for adults translated from Chinese into English in 2025. Make sure to open the hidden menus to see a list of shorter pieces published online and in journals this year (many of which can be read for free!), as well as the licensed internet fiction that received new volumes in print.

2025 Roll-Call of Chinese Poetry in English Translation

By Andrew Rule, December 22, '25

Another year, another roll call! As has long been tradition at Paper Republic, we're rounding out the year with a list of all the Chinese literature that came out in English translation over the last twelve months. This year's list also includes shorter pieces published online and in magazines and anthologies, making it a more comprehensive snapshot of the state of the field than ever before. Today, we unveil the poetry list, followed by the adult fiction and nonfiction lists tomorrow, and the children's literature list on Wednesday.

Paper Republic Newsletter 24: Counting Down to Christmas

By Yao Lirong, December 10, '25

While we’re counting down to Christmas, we’re also celebrating a number of wonderful updates from our community over the past two months!

We’re delighted to share that Shuang Xuetao's The Hunter, translated by Jeremy Tiang, and Jia Pingwa's Old Kiln, translated by James Trapp, Olivia Milburn, and Christopher Payne, have been included in The Irish Times' “Books of the Year” list. Congratulations to all involved!

We also extend our congratulations to Amadan Ruiqing Flynn for winning the 2025 Golden Point Award for her translation of Liew Kwee Lan’s (艾禺) The Boy Who Cried Bear (《有熊出没》).

And, the good news don't just stop here! Read on below.