Our News, Your News

By Jack Hargreaves, July 12, '20

This week's Sunday Sentence is something entirely different: Yeng Pway Ngon 英培安 inserts himself into the narrative on page 25 of 《骚动》(2002), translated by Jeremy Tiang as Unrest. Thank you to Jeremy for setting this week's challenge.

Please input your translation in the comments box at the bottom of the page.

The sentence to translate is:

我启动电脑的时候,小说的女主人翁和男主人翁正在床上。我的手指在键盘上犹疑了好一阵子,不能决定应该由我还是由他们其中一人来叙述这场性爱。无论如何,窥视小说主人翁的私生活是读者的权利,所以作为读者的你是可以看到的,床上的性活动正在进行中,男主人翁的状态似乎并不理想。

Remember, you can post your translation anytime between now and next Sunday, so you have plenty of time to ponder and refine it.

More…

By Jack Hargreaves, July 4, '20

This week's Sunday Sentence can be found on the first page of 《北妹》 by Sheng Keyi 盛可以 (2004), translated by Shelly Bryant as Northern Girls (2012).

Please input your translation in the comments box at the bottom of the page.

The sentence to translate is:

一米五五的样子,短发、带卷、蛋脸偏圆,基本上是良家民女的模样,嫁个男人安分守己生儿育女的胚子。遗憾的是,钱小红的胸部太大,即便不是钱小红的本意,也被毫无余地地划出良民圈子,与寡妇的门前一样多了事。

Remember, you can post your translation anytime between now and next Sunday, so you have plenty of time to ponder and refine it.

More…

I spent the early parts of the book alert for allusion or deeper meaning, either about human nature or about contemporary China, but I think the book can be taken at face value as a character-driven story about the suddenness and the burden of violence. Some other themes are ever-present: madness, for instance, ghosts, and the vicissitudes of the modern world (e.g., “There’s no shame in losing your soul; the way the world is going now, it’s happening to lots of people”, and the Taiwanese businessman referring to Miss Bai’s foetus as a ‘futures deal’). I happened to have read Crime and Punishment shortly before reading this and there are a lot of parallels for all three characters about the burden of crime and violence. It is like an existentialist Mexican stand-off, and the overall impact is deeply affecting.

By Chen Dongmei, July 3, '20

We’re very happy to announce that David Perry is our first resident translator for the Paper Republic / Librairie Avant-Garde Chenjiapu Translator Residency (陈家铺平民书局汉学家驻留计划) !

The residency, organized in collaboration by Librairie Avant-Garde (先锋书店) and Paper Republic, offers translators a chance to join the Paper Republic & Librairie Avant-Garde literary family, and work on literary projects in the midst of a traditional Chinese rural environment.

In 2018, Librairie Avant-Garde launched the Chenjiapu Populace Bookstore, the third of LAG’s village bookstores. Along with the bookstore, LAG remodeled a house into a residency venue for authors, poets and other literary creatives. The residency has hosted A Yi, Li Juan, Yu Xiuhua, and Ou Ning, among others. The bookstore also holds an annual poetry festival called “Third Day of Third Month” (三月三).

David Perry is a poet and translator. He holds a MFA in Literary Translation from University of Iowa and currently teaches core curriculum writing and creative writing at NYU Shanghai as a senior lecturer. He’s staying at Chenjiapu for two weeks in July, and working on the translation of the Nanjing-based poet Sun Dong’s work.

This project came together thanks to Qian Xiaohua, Li Xinxin and Li Xia from Librairie Avant-Garde, as well as author A Yi.

Cover photo by David Perry

More…

By Jack Hargreaves, June 26, '20

Sunday Sentence #5 comes from an unreleased book, 《鹰头猫与音乐箱女孩》 by Dorothy Tse 謝曉虹, due out with Aquarius in July 2020 (next month!) and currently being translated by Natascha Bruce with the working title, Owlish & the Music-Box Ballerina.

Please input your translation in the comments box at the bottom of the page.

The sentence to translate is:

因此,在那空气黏稠、沉甸甸令人脑袋发胀的冬日下午,当教授Q习惯性地从家里那扇狭小的镶了不锈钢窗花的窗口看出去时,竟然没有看到海,没有看到从天而降,锋利如刀片的阳光把它任意割切成许多玻璃似的碎片,没有看到一直停泊在海湾里几条颜色明艳,充满了战意的船,以及它们那些不断深入海床里的机械吊臂。

And for anyone who fancies it, here is the sentence that finishes the paragraph:

教授Q看到的是一个居住了多年的城市,从内部渐渐膨胀起来,形成一个饱满的头颅,并慢慢回转过来,向他展示了另一张脸。

Remember, you can post your translation anytime between now and next Sunday, so you have plenty of time to ponder and refine it.

More…

“Stupid dog!” “Go F--- yourself, shame on u.” “How does the steamed bun soaked in human blood taste? You white-skinned pig!” Those were among the first messages I received on April 8 on the Chinese social media platform Weibo. Over the next few hours, more than 600 similar messages would be posted. I was accused of being a CIA agent. There were death threats. For the next several weeks, the insults and threats multiplied, and the message board that housed them would be viewed more than 3 million times.

What terrible offense had I committed to elicit this deluge of hate? I had translated “Wuhan Diary,” an account by Chinese author Fang Fang of covid-19’s spread in her hometown.

The entire process of translation, proofreading and sales of the foreign language edition of this book was completed within just over 10 days. Behind this “rapid publication” are the obvious efforts of anti-China forces attempting to stigmatize the anti-epidemic efforts of the Chinese people.

By Jack Hargreaves, June 20, '20

Week 4 of Sunday Sentence! Halfway through!

A lesser-known writer this week, but one of my favourites, Yang Dian 杨典 and the two opening sentences of his short story, 《朱厌》, which I've tentatively translated for the purposes of this exercise as 'Ape of War'. The story is taken from his as-yet untranslated 2019 collection, Stories from the Goose Cage 《鹅笼记》.

Please input your translation in the comments box at the bottom of the page.

The sentences to translate are:

前朝灭亡的最后一个夏日,我那位集病夫、书生、杀手与某秘密社团激进分子于一身的兄弟,我窝藏多年的故知,我不可同日而语的镜子,终于在十字路口法场走到了魂断他乡的绝境。他的死是在我意料中的。

Remember, you can post your translation today or any day next week, so you have plenty of time to think about it and there's no need to rush.

More…

Submission deadline 17th July 2020. For suggested poems, click on Mandarin Poems tab. Poems sourced by Paper Republic.

By Jack Hargreaves, June 14, '20

For week 3 of Sunday Sentence, we're turning to one of the best-known Chinese writers of the 20th Century, Zhang Ailing, and the opening line of her book, 《色戒》(1979), translated by Julia Lovell and released in 2007 as, of course, Lust, Caution. Thanks to Dylan Levi King for suggesting this "deceptively simple" peach of a sentence.

Please input your translation in the comments box at the bottom of the page.

The sentences to translate are:

麻将桌上白天也开着强光灯,洗牌的时候一只只钻戒光芒四射。白桌布四角缚在桌腿上,绷紧了越发一片雪白,白得耀眼。

Remember, you can post your translation today or any day next week, so you have plenty of time to think about it and there's no need to rush.

More…

Wang, who is sixty-five, couldn’t focus on the novel she was working on, and, on the third night of lockdown, she typed up a four-paragraph blog entry and posted it on Weibo, a Twitter-like platform, where she has about 4.8 million followers. “I really should start writing about what is happening. It would be a way for people to understand what is really going on here on the ground,” she wrote. Her posts became a daily ritual; they grew longer, her tone more forceful. Almost immediately, the essays drew a large following—some readers professed that they would stay up until a post was published, unable to sleep until they’d read that day’s entry—and also attracted censorship and vicious criticism. In May, HarperCollins published “Wuhan Diary,” an English translation of her collection of lockdown essays.

By Jack Hargreaves, June 6, '20

For this week of Sunday Sentence, we have something entirely different:

a big announcement taken from page 118 of Yan Ge's 颜歌《我们家》(2013), released in 2018 as The Chilli Bean Paste Clan,

translated by Nicky Harman.

Please input your translation in the comments box at the bottom of the page.

The sentences to translate are:

他遂自己端起杯子来把里头的酒喝了,要把勇气豪气和阳气都鸡巴喝出来。“给你们说,”他宣布,“老子又把婆娘的肚皮搞大了。”

Remember, you can post your translation today or any day next week, so you have plenty of time to think about it and there's no need to rush.

More…

By Jack Hargreaves, May 30, '20

And we're off!

This is the first week of Sunday Sentence, so if you missed the post explaining the activity, click here for more details.

Otherwise...

To start we have three sentences for you to translate, taken from page 13 of Jin Yong's 金庸 《射雕英雄传》(first released in 1959), entitled A Hero Born (Legends of the Condor Heroes 1) in Anna Holmwood's translation.

Please input your translation in the comments box at the bottom of the page.

The sentences to translate are:

他脚步甚快,顷刻间奔出数丈。曲叁右手往怀中一掏,跟着扬手,月光下只见一块圆盘似的黑物飞将出去,托的一下轻响,嵌入了那武官后脑。那武官惨声长叫,单刀脱手飞出,双手乱舞,仰天缓缓倒下,扭转了几下,就此不动,眼见是不活了。

Remember, you can post your translation today or any day next week, so you have plenty of time to think about it and there's no need to rush.

More…

By Jack Hargreaves, May 28, '20

Eyes peeled and pens sharpened everyone!

This Sunday 31st May begins a two-month activity of online translation workshopping which anyone and everyone who knows Chinese and writes English can get involved with. A famously lonely endeavor, translation, when done with others, becomes a rambunctious language game in which all the best nitpicking and head scratching go on. So since face-to-face workshops are called off for the foreseeable future, Paper Republic is launching Sunday Sentence, or in Chinese, 一周一句!

Every Sunday a sentence will be posted here on the website as well as on Twitter and Facebook, and you are invited to have a go translating it! The sentences have been picked by PR team members and other CH-EN translators for being particularly challenging to render in English for some reason or another, challenging enough we hope to produce endless different possible translations and start some discussion around the strategies people employ when translating literary Chinese and the reasons behind their decisions. All translations and discussion should be posted in the comment sections of the Sunday Sentence page when it goes online.

First up is a sentence picked by Anna Holmwood, translator of Jin Yong! So to whet your wuxia appetite, from this Saturday onward, you can listen to Angus Stewart’s conversation with another translator of Jin Yong, Gigi Chang, on the Translated Chinese Fiction podcast

See you this Sunday!

Our Read Paper Republic: Epidemic series is going global! Here's A Yi's A Message Held to the Flame in Spanish!

As the lockdown continued, Fang Fang's popularity grew. Publishers then announced that they would collate her entries and publish them in several languages.

But Fang Fang's growing international recognition has come with a shift in the way she is viewed in China - with many angered by her reporting, even branding her a traitor.

Ms. Yu’s later attempts to publish stories in English, however, were rejected by American publishers. “They were only interested in stories that fit the pattern of Oriental exoticism — the feet-binding of women and the addiction of opium-smoking men,” she once recalled in an interview. “I didn’t want to write that stuff, I wanted to write about the struggle of Chinese immigrants in American society.”

Writers in lockdown are, like everyone else, feeling pale and postoperative. The pandemic has thrown a spanner into best-laid plans. A diary, as soldiers, prisoners and invalids have long understood, can be a good way to write oneself out of a bad spot.

The Chinese novelist Fang Fang lives in downtown Wuhan, the epicenter of the coronavirus outbreak. After that city went into quarantine in January, she began keeping an online diary about her experience. Wuhan remained shut down for 76 days, and is still struggling to return to anything resembling normalcy.

By Dylan Levi King, May 17, '20

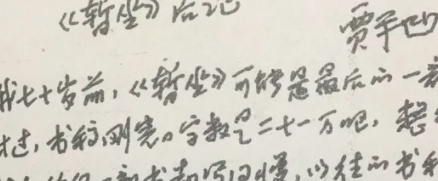

When Nicky Harman and I received Jia Pingwa’s invitation to visit him in Xi’an last spring ("Jia Pingwa's Hometown"), apart from being mobbed by fans at an opera performance and shepherded through a tour of Xi Zhongxun’s old cave home by enthusiastic local bureaucrats and Party functionaries (many not even born when Jia’s literary stardom reached its first peak in the early 1990s), the most surreal experience was poking around his writing desk. The desk itself is obscured completely by towers of books. To get to the chair he sits at to write, which is draped with fur, you need to be slim enough to slide between two walls of stacked up novels, reference manuals, works on local customs history books, and volumes of poetry. The available work area on the desktop is also limited—there are too many books piled up, and there has to be room for a carton of cigarettes and an ashtray, too. When we visited in the spring, the small amount of available work area was covered in pages from a novel that he was writing—black felt-tip pen on white pages, longhand—a biscuit tin (for completed pages), and left open beside it, a book of Eileen Chang short stories.

He told us that it would be an urban novel.

That would make it his first extended return to the city since Happy Dreams 高兴 in 2007 (it’s a book he doesn’t consider an urban novel, since it concerns migrant workers from the countryside).

Of course, his novels are invariably never about just the city or just country, but about the tension between them, characters trapped perpetually in between. The idea of an extended return to the city, though, years on from urban novels like White Nights 白夜, was intriguing.

When I returned late last summer for the 29th China National Book Expo ("迪兰先生, world famous Sinologist / 第29届书博会"), Jia was talking publicly about a city book, for which he was still working on final drafts.

The novel (or perhaps novels) will be published by the Writers Publishing House 作家出版社 in July, and some lucky people have already gotten their hands on it, but the Jia Pingwa Research Institute 贾平凹文化艺术研究院 earlier today posted the afterword of the announced novel:

贾平凹:长篇小说《暂坐》后记

The Jia Pingwa afterword is almost a genre in itself. It's the reason why Jia's novels are best started from the rear—you need the afterword to explain what you're about to read.

In the afterword to Sit Awhile 暂坐, Jia explains that the germ of the novel was a tea shop in his building, where he drank tea twice a day, and his observations of the peculiar world of the owner and the women that drifted through. He writes in this novel about women, mostly, he says, because he lacked confidence. “I found myself no longer writing the women, but the women writing me.”

It makes sense now why he might have been referring back to Eileen Chang’s short stories. I quite like the idea of Jia Pingwa attempting a Chu T'ien-wen-style novel about the interconnected lives of urban women.

Earlier this year, I wrote about the Nicky Harman's masterful translation of Jia's Broken Wings 极花 for ACA ("‘Broken Wings’: Jia Pingwa’s Controversial Novel Explores Human Trafficking And Rural China"), and noted the sharp criticism that followed its original publication, with the author branded a male chauvinist. On the contrary, I've always found Jia's women characters mostly sympathetic and—in recent books, at least— usually rendered with more care than his male characters. But it will be interesting to see if the critics that appeared for Broken Wings will pop up again.