When Nicky Harman and I received Jia Pingwa’s invitation to visit him in Xi’an last spring ("Jia Pingwa's Hometown"), apart from being mobbed by fans at an opera performance and shepherded through a tour of Xi Zhongxun’s old cave home by enthusiastic local bureaucrats and Party functionaries (many not even born when Jia’s literary stardom reached its first peak in the early 1990s), the most surreal experience was poking around his writing desk. The desk itself is obscured completely by towers of books. To get to the chair he sits at to write, which is draped with fur, you need to be slim enough to slide between two walls of stacked up novels, reference manuals, works on local customs history books, and volumes of poetry. The available work area on the desktop is also limited—there are too many books piled up, and there has to be room for a carton of cigarettes and an ashtray, too. When we visited in the spring, the small amount of available work area was covered in pages from a novel that he was writing—black felt-tip pen on white pages, longhand—a biscuit tin (for completed pages), and left open beside it, a book of Eileen Chang short stories.

He told us that it would be an urban novel.

That would make it his first extended return to the city since Happy Dreams 高兴 in 2007 (it’s a book he doesn’t consider an urban novel, since it concerns migrant workers from the countryside).

Of course, his novels are invariably never about just the city or just country, but about the tension between them, characters trapped perpetually in between. The idea of an extended return to the city, though, years on from urban novels like White Nights 白夜, was intriguing.

When I returned late last summer for the 29th China National Book Expo ("迪兰先生, world famous Sinologist / 第29届书博会"), Jia was talking publicly about a city book, for which he was still working on final drafts.

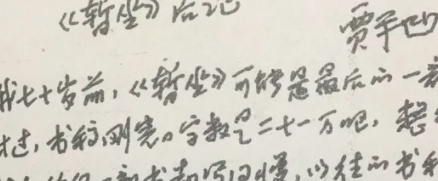

The novel (or perhaps novels) will be published by the Writers Publishing House 作家出版社 in July, and some lucky people have already gotten their hands on it, but the Jia Pingwa Research Institute 贾平凹文化艺术研究院 earlier today posted the afterword of the announced novel:

The Jia Pingwa afterword is almost a genre in itself. It's the reason why Jia's novels are best started from the rear—you need the afterword to explain what you're about to read.

In the afterword to Sit Awhile 暂坐, Jia explains that the germ of the novel was a tea shop in his building, where he drank tea twice a day, and his observations of the peculiar world of the owner and the women that drifted through. He writes in this novel about women, mostly, he says, because he lacked confidence. “I found myself no longer writing the women, but the women writing me.”

It makes sense now why he might have been referring back to Eileen Chang’s short stories. I quite like the idea of Jia Pingwa attempting a Chu T'ien-wen-style novel about the interconnected lives of urban women.

Earlier this year, I wrote about the Nicky Harman's masterful translation of Jia's Broken Wings 极花 for ACA ("‘Broken Wings’: Jia Pingwa’s Controversial Novel Explores Human Trafficking And Rural China"), and noted the sharp criticism that followed its original publication, with the author branded a male chauvinist. On the contrary, I've always found Jia's women characters mostly sympathetic and—in recent books, at least— usually rendered with more care than his male characters. But it will be interesting to see if the critics that appeared for Broken Wings will pop up again.

Comments

There are no comments yet.