Our News, Your News

By Eric Abrahamsen, December 17, '20

Paper Republic became a Charitable Incorporated Organization in the UK in February of 2019, and our first annual report is now due. We got sort of excited, and made a nice-looking report detailing all the fun we've had in the past year, and some of the fun we've got planned for the next year.

It seemed like a nice idea to post this at the same time as our traditional annual roll call of new translation publications, so here you are! Our annual report is here, and the 2020 roll call is here. Enjoy!

By Nicky Harman, December 17, '20

2020: torrid times. Not all of the ones on our 2020 Forthcoming Translations (posted in December 2019) made it into publication this year, but a number of translations from Chinese have still come out.

Kudos to writers, translators and publishers alike!

More…

By Bruce Humes, December 13, '20

In this interview, Pema Tseden --- who writes in both Tibetan and Chinese, and is the first director to shoot a major film entirely in Tibetan --- calls for wider distribution of films that focus on China's ethnic minorites.

"Art film enriches film culture and creativity. If we don’t support it, we’ll only see movies of the same type. A vicious circle will form, wherein audiences think this is what movies are like and cinemas think audiences only accept a certain kind of movie. Ultimately, that will harm the whole industry — creators won’t persist if the market is always like this."

How can we understand China if we don’t know what its most prominent intellectuals are saying? A translation project by David Ownby aims to make up for the absence of Chinese voices in Western discussions about the country that nobody can afford to ignore.

By Helen Wang, December 10, '20

Nicky Harman has just won a major award in China - The Special Book Award of China. It’s the 14th year of the awards and they are a big thing. As she was unable to attend the ceremony in China, on Monday, one of her publishers (Sinoist Books) and Guanghwa Bookshop organised a surprise zoom party for her, inviting the Chinese Cultural Attaché, her authors and friends in the Chinese literature community around the world either to attend in person or to send a short video recording. It was wonderful to see everyone! Even the Cultural Attaché, whose role was to be the official, was bowled over by the genuine friendship and informal atmosphere of the occasion - and that it was a meeting of friends! The organisers have just put the highlights on Youtube - https://m.youtube.com/watch?feature=youtu.be&v=jsW1aUsPvds.

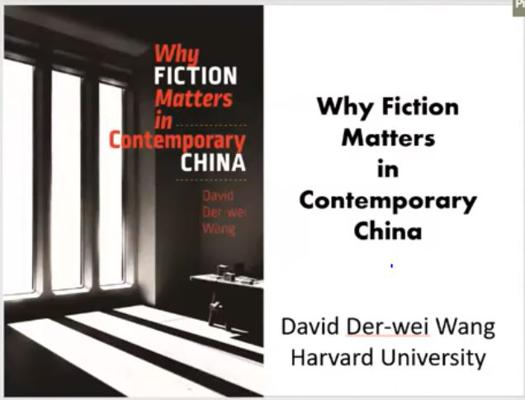

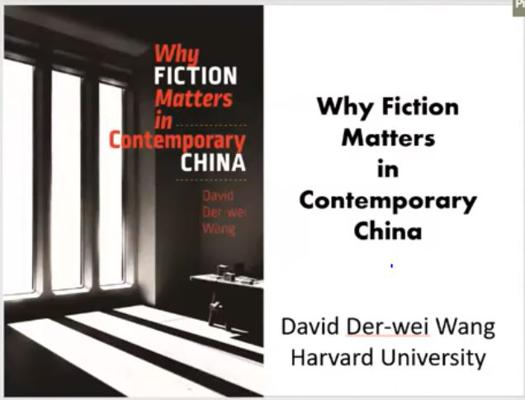

Talk by Prof David De-Wei Wang to the Institute of Chinese Studies, Delhi

(Wang's new book "Why Fiction Matters in Contemporary China" - UP of New England, Brandeis Imprint, Dec 2020, ISBN 9781684580262)

Call for Applications: Two series co-editors, one with expertise in Asian literatures and one with expertise in Middle Eastern and/or African literatures, for Best Translations: An Annual Anthology, a new publishing project

By Jack Hargreaves, December 3, '20

The final sentence of series one went up in mid-July. By the end of the week, the total number of translations contributed since the game's beginning by lots of lovely translators, one of whom doesn't read Chinese and two of which were computer programmes, had reached 139 -- if I've counted right that is, which I don't think I did, so let's just go with 'enough to consider a second series'. So here it is!

Well actually, first, we'd like your help. That's right, not only are we asking you to translate this time around, we're inviting you to suggest the sentences too!

Please send any sentence (or two) from Chinese-language fiction that excites, dazzles, bamboozles or floors you to jack@paper-republic.org (sentences from short stories particularly welcome —— you'll find out why later!).

With every submission, please include: the sentence, book/story it is taken from, page number (if you know it), author, and a little context.

We'll start the new series in 2021.

If you missed series one and you're wondering what this is all about, have a look at the series intro here, with links to the sentences we translated over the eight weeks.

Looking forward to seeing what you come up with!

For the very first time, Sanmao – a name that is so widely known to generations of Chinese readers – has been translated into English by Chinese-American writer and editor Mike Fu.

Join a discussion between Mike and Nicky Harman, who have both translated Chinese women authors with transnational writing experience.

By Bruce Humes, November 25, '20

They are Fang Fang, author of Wuhan Diary, and Uyghur writer Muyesser Abdul'ehed (pen name Hendan Hiyal), now living overseas in Istanbul.

All 100 listed here.

By Bruce Humes, November 20, '20

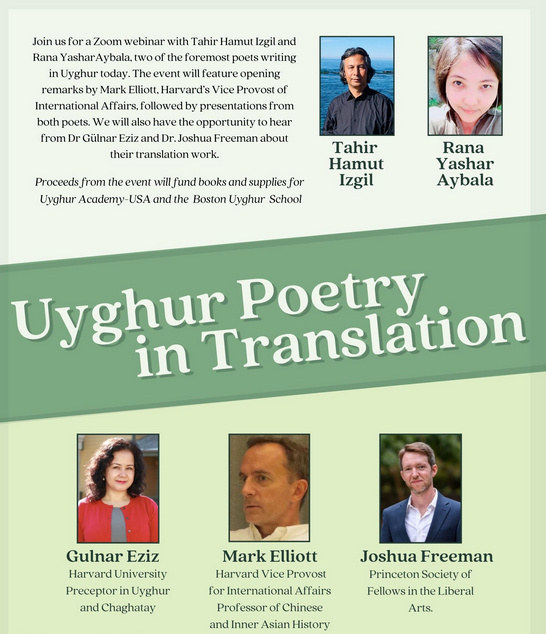

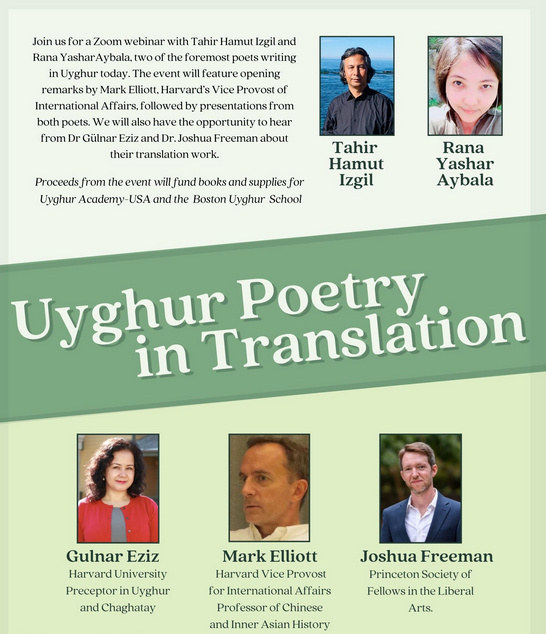

"Uyghur Poetry in Translation" live online

November 24, 2020 (12:00-13:15, Eastern Time, US)

Opening remarks: Mark Elliott, Harvard’s Vice Provost of International Affairs

Poets performing: Tahir Hamut and Rena Yashar Aybal

Translators to speak: Dr Gülnar Eziz (Harvard Preceptor in Uyghur and Chaghatay), and Dr. Joshua Freeman (Princeton’s Department of East Asian Studies)

Register here

Watch a literary exploration of the city of Shanghai as part of a very special event, showcasing Comma's city anthology The Book of Shanghai, which features ten contemporary Chinese authors. The two contributing authors Chen Danyan and Wang Zhanhai will share with you what it is like to be a young, female writer in China today, writing about the lives of urban Chinese residents.

A joint event between the Confucius Institute at the University of Manchester and Comma Press.

Short stories are under-represented in translation but they have much to offer. Eric Abrahamsen and Dylan Levi King discuss why readers, and publishers, should dive in.

The awards were announced on 12 November 2020 at the China Shanghai International Children's Bookfair. (For winners in previous years, see Wikipedia)

By Bruce Humes, November 9, '20

Angus Stewart recently interviewed me about translating Chi Zijian's novel that chronicles the tragic twilight of the reindeer-herding, Tungusic-speaking Evenki of northeastern China. The tale has since been translated into several languages, including French, Japanese and Swedish (see comments section for URLs).

More…

By Bruce Humes, November 7, '20

This workshop aims to explore the shifting definitions of the borderland as a territorial gateway, a geopolitical space, a contact zone, a liminal terrain, and an imaginary portal. To this end, participants will explore the intersection of ethnic, linguistic, cultural, and ecological dynamics that inform the cartography of the Chinese borderland, from the Northeast to the Southwest, from Inner Mongolia to Tibet, and from Nanyang to Nanmei.

For workshop speakers/themes, click here.

To register and receive a Zoom link, please click here.

Highlights:

Yanshuo Zhang (University of Michigan): Shen Congwen’s Idealized Ethnic: Borderland, Ethnicity, and the Spiritual Enchantments of a Modern Master

Christopher Peacock (Columbia University): “Unsavory Characters: Forced Bilingualism in the Tibetan Fiction of Tsering Döndrup”

Mark Bender (Ohio State University): “Treading Poetic Borders in Southwest China and Northeast India”

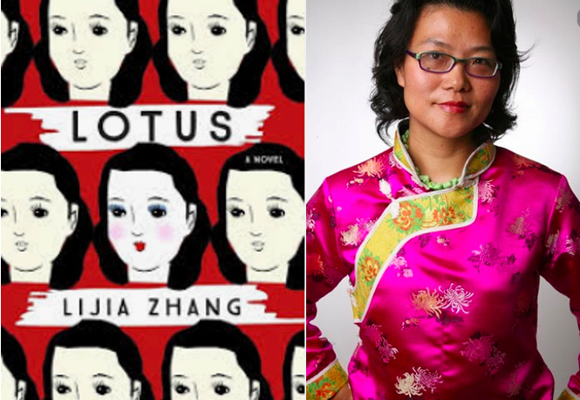

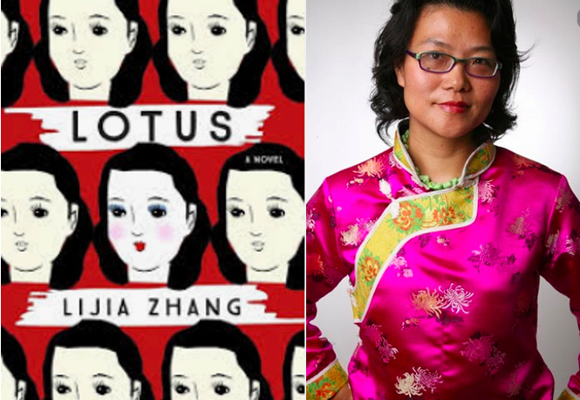

A real-time, online Q & A with Zhang Lijia, author of 'Lotus,' a novel set in Shenzhen in the year 2000.

Tue, Nov 10 · 8:00 PM GMT

"Lotus is a rollicking, sexy novel, but it's not just another fun read. The novel provides so much insight into the underside of China's roaring economy and the immense pressure on young migrants to get rich quick. In Lijia Zhang's tour of the sex industry, you'll find not only sleaze, but soul."

--Barbara Demick, former China bureau chief for the Los Angeles Times.

Reports NPR: "... if you want to write fan fiction anywhere in China, you have to do it under an account that's linked to your real name."

By Eric Abrahamsen, October 30, '20

From the press release:

The Newman Prize honors Harold J. and Ruth Newman, whose generous endowment of a chair at the University of Oklahoma enabled the creation of the OU Institute for US-China Issues in 2006. OU is also home to the Chinese Literature Translation Archive, Chinese Literature Today, World Literature Today and the Neustadt International Prize for Literature.

Juror Eric Abrahamsen said of the winner, “Yan’s writing does for the Chinese heartland what John Steinbeck did for the American West, or Thomas Hardy for Southwest England…he remains vitally invested in the ethical responsibility of the author. Though it has been demonstrated to him again and again that his explorations of China’s historical trauma are not welcome, he seems not to take the hint, and persists in laying bare what he sees as the original sins of modern Chinese society…His stubbornness, and the perpetual freshness of his sorrow over historical tragedy, are worthy of respect.”

See below for the full text of the press release.

More…