Our News, Your News

By Bruce Humes, February 28, '20

GoogleTranslate offers translation to/from several of China's indigenous languages, the latest being Uyghur.

Others are Kazakh, Korean, Kyrgyz and Mongolian.

Turkmen and Tatar have also just joined the club -- and Turkish had long been available -- so Google Translate is doing a decent job of adding Turkic languages.

But in terms of written scripts used by a large number of PRC citizens, one stands out as missing on this list: Tibetan. It appears that its inclusion is underway, but I don't have any details.

編者按:本文是閻連科2月21日在香港科技大學網絡授課的第一講,端傳媒獲閻連科授權,轉載全文

同學們:今天是我們科大研究生班網絡授課的第一講。開講前請允許我說些課外話。

小時候,當我連續把同樣的錯誤犯到第二、第三次,父母會把我叫到他們面前去,用手指着我的額頭問:

「你有記性嗎?!」

當我把語文課讀了多遍還不能背誦時,老師會讓我在課堂上站起來,當眾質問到:

「你有記性嗎?!」

By David Haysom, February 25, '20

The One-Way bookstores have been a home for literature for the last fifteen years, providing space on their shelves for the kind of books that are hard to find anywhere else, as well as hosting literary talks and events with local and international authors. Now, with the impact of COVID-19 bringing their business to a standstill, they are in need of donations just to be able to keep paying rent.

In this Wechat post they explain that they have only been able to keep one of their four stores open. That one store, in a Beijing shopping mall that now has a tenth of its usual customers, has been selling no more than a handful of books a day. Restrictions on delivery services have also taken a huge chunk out of their online sales.

OWSpace are the publishers of One-Way Street Magazine (单读): an outstanding literary journal, a rare independent voice in contemporary Chinese media, and our collaborators for the "Read Paper Republic: Dispatches" series of creative non-fiction pieces. Last year, a profile in Neocha described the publication as "a journal that thinks books and ideas are worth arguing about [...] a platform for opinions, articles of faith, and moments of doubt—in short, a public conversation about cultural life."

To support OWSpace and One-Way Street Magazine – and everything they do for the literary scene in China – you can make a donation here.

Did you know that, like many of China's major seaports, Hankou (Wuhan) hosted concessions granted to the British in 1858, and eventually the Belgians, French, Germans, Japanese and Russians?

Anna Gustafsson Chen has interviewed Jennifer Feeley, and reviewed her translation of Chen Jiatong's children's novel White Fox. Two consecutive posts - read them both!

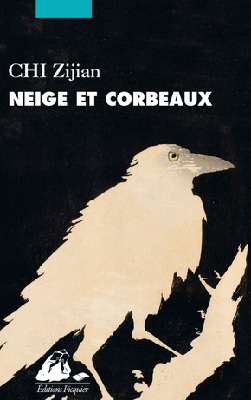

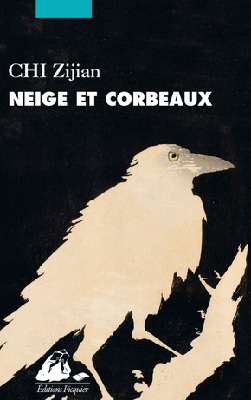

For those of you who would like to learn a bit about China’s pre-21st century experience in dealing with epidemics, I’ve woven together three topical items, all of which center around an epidemic that took place in early 1900s China. They include news about the upcoming launch of a French translation of a “plague” novel — 《白雪乌鸦》by a Chinese author — and an English excerpt (in case your French isn’t quite up to par) . . .

Bertrand Mialaret's latest essay discusses various French and English translations of Yan Lianke's novels

By Bruce Humes, February 5, '20

Just got the following email from a publisher of translated contemporary Arabic literature:

Email content

Pretty impressive: One-click access to video of author speaking (in Arabic with English sub-titles) about the novel; lengthy English-language extract; background info about the author; link to publisher's blog where one can find some authors personally reading their work, etc.

Has any publisher of Chinese literature in translation done something along these lines?

In Beijing’s night, neon lights flash on and off and the shadows of Beijing’s inhabitants flicker indistinctly. Packs of cars on the main roads form a river of light. In the midst of that river—constantly flowing like the kleshas of desire, hatred, and ignorance and glittering like the variegated colors of the objects of earthly desire—the lights spewed forth from the depths of the night.

(translated by Kati Fitzgerald)

From the book’s earliest essays, it becomes clear how Sanmao’s whimsical solo traveler persona came to symbolize an alternative way of life among her earliest generation of readers, whose own lives were shaped by the oppressive political environments of mainland China and Taiwan during the 1970s.

By Bruce Humes, January 27, '20

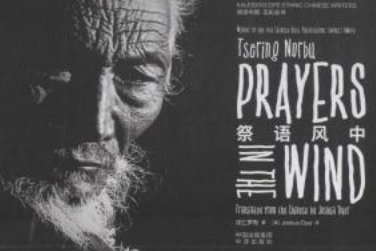

Two potentially controversial novels — one by a Uyghur author, and the other by a Tibetan — have recently been published in English. They are part of the Kaleidoscope Series of China’s Ethnic Authors sponsored by China Translation & Publishing House, a dozen or so novels by authors that highlight tales in which non-Han culture, motifs and characters play a key role (民族题材文学).

Patigül’s Bloodline (百年血脉) relates the semi-autobiographical tale of a Xinjiang native, daughter of a Uyghur father and Hui mother, who marries a Han, and struggles to bring up a family in mainstream Chinese society. Told in the first person, it unflinchingly describes her mother’s mental illness, her brother’s agonizing death from an STD and tribulations of a “mixed” marriage. For an English excerpt, visit here.

Tsering Norbu’s Prayers in the Wind (祭语风中) narrates the subsequent life of a Buddhist monk who attempts — unsuccessfully — to exit China in the wake of the 1959 Tibetan uprising and the Dalai Lama’s flight to India. For an excerpt, visit here.

By Nicky Harman, January 23, '20

Registration for the Warwick Translates Summer School has now opened! Details here. It takes place 8-12 July 2020 inclusive, and there will be a Chinese-to-English option, led by Nicky Harman.

Perhaps the most welcome development of all was an English-language translation of Louis "Jin Yong” Cha Leung-yung’s wuxia Condor trilogy, overseen by Anna Holmwood and published by the MacLehose Press. All the concerns of English-speaking editors, who wondered whether readers outside China could cope with Cha’s epic, almost metaphysical fights, melted away in the course of two wonderful novels. A Snake Lies Waiting, part three of a projected 12 books, is due in early 2020. Sadly, Cha died only a few months after part one was released, in 2018.

The success of all these books owes much to an impressive generation of translators, arguably the most famous of whom is Ken Liu. An admired novelist in his own right, he is even more celebrated for his role in this golden age of Chinese science-fiction.

His first act was to translate the Three-Body Problem trilogy, by Liu Cixin, which has become a global phenomenon since part one appeared in 2014 (six years after the Chinese version).

On Saturday June 29, 2019, Britain’s third plaque to a Chinese person – the writer and artist Chiang Yee (蒋彝) – was unveiled in the university town of Oxford.

Du Fu, the eighth-century Chinese poet now lauded as one of the greatest wordsmiths who ever lived, resided in a humble thatched hut in Chengdu at the peak of his literary life. He wrote lyrically about cooking cold noodles garnished with the leaves of the scholartree, but he never had a fried chicken sandwich or a Pepsi. Yet at a KFC in the heart of Chengdu, a holographic pyramid beams 3-D images of his hut in spring, summer, winter, and fall.

In a new essay on author Xiao Hong (萧红), Mialaret points out that neither film director Ann Hui nor literary translator Howard Goldblatt seem to have done justice to her work.

Mialaret also notes a 2019 French translation of her 《呼蘭河傳》, Souvenirs de Hulan He by Simone Cross-Morea.

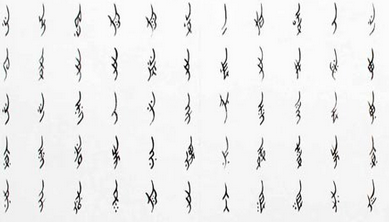

On an auspicious day, two families from Ne’u na Village, a small village along the Yellow River in Western China’s Qinghai Province, gather to celebrate a wedding. The day has been chosen specifically for this purpose. Midway through the wedding banquet, a man stands before the crowd already so drunk that his words are almost unintelligible, and he speaks. He begins with an invocation to several deities, and then a statement about how auspicious this day is and how it has been chosen specifically for this purpose. After describing the beautiful dress of the bride down to the smallest hair ornament, he begins to describe Tibet and its geographic and historical relations with Nepal and China. Next, with exquisite imagery, he tells of the unique physical environment of the Tibetan plateau, and finally he discusses the beauty and auspiciousness of the very village in which the wedding is being held. At every turn this area and its people are described with detailed references to the religious and natural worlds in which Tibetans live. The speech is the highlight of the wedding in Ne’u na. Following the speech, guests offer gifts to the new couple—first from the groom’s side, then from the bride’s—and people from both sides begin antiphonal singing until late into the night.

Most of China’s major entertainment publications thoroughly cover the Oscars each year, so when the Academy announced its 15 shortlisted films for the 2020 Best Documentary Feature award, many Chinese publications covered it. But each paper had a peculiarity in common: they each listed only 14 films.

One Child Nation, the documentary about China’s one-child policy that I co-directed with my friend Jialing Zhang, is included in this year’s shortlist, but no Chinese publication has made any mention of it. Any person living in China who might be following the Oscars would have no way of knowing that a Chinese film is a contender in this year’s documentary category. Even for people who have heard of the film, searching for the Chinese translation of the film’s title (独生子女国度 or 独生之国) within China generates no results, except for this message: “the result of this search cannot be displayed because it violates related laws and regulations.”

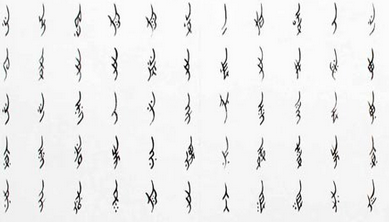

When I was a university student in Beijing in the early ’90s, I stumbled upon an academic article by Zhao Liming, a professor at Tsinghua University’s Chinese language department, about a little-known script used only by women in a corner of the southern province of Hunan. Days after, I bought the small book she had written on the subject, Nüshu—A Surprising Discovery, and read it as fast as my eyes, and my Chinese reading skills, allowed. I was hooked: The word nüshu refers to a script used by women in Jiangyong—a small county in the province’s southernmost tip—to transcribe the local lingo. As soon as I could, I made the first of many trips there.

By David Haysom, December 28, '19

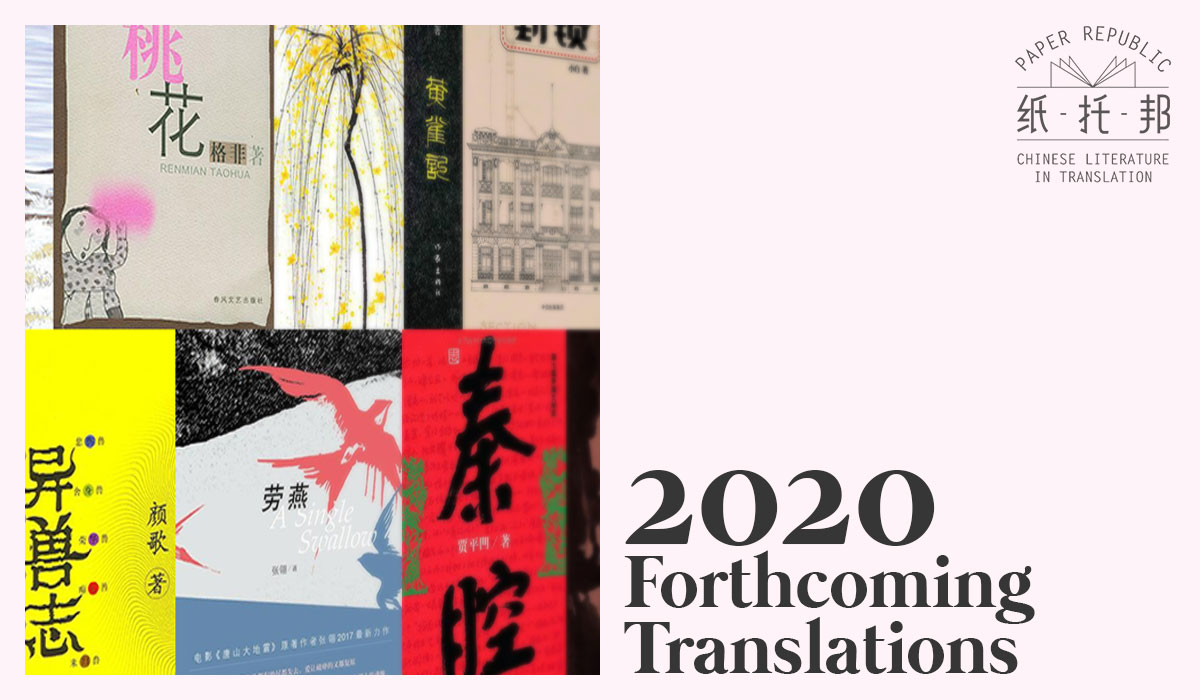

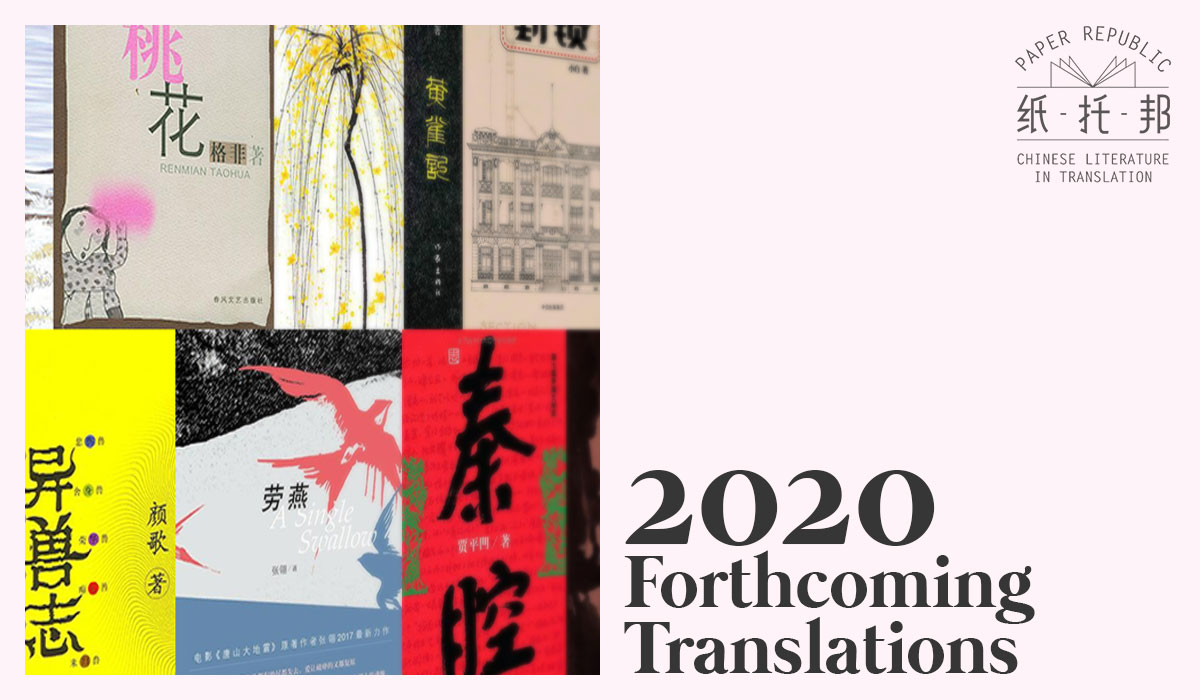

Now you've read our 2019 lists of English translations and books published in Chinese, here's a preview of some of the translations that will be hitting your shelves in 2020!

More…

The Communist Party’s publicity department told publishers this year that the total number of books getting approvals would shrink, that domestic authors would be favored and that titles that promoted the party and China’s capitalism-infused version of socialism would be most encouraged.

If the enemy commander is avid for advantage, use

it to lure him in;

If he is volatile, seize upon that;

If he is solid, prepare well for battle;

If he is strong, evade him.

If he is angry, rile him.

If he is unpresuming, feed his arrogance.

By David Haysom, December 21, '19

As the year comes to a close, we’ve asked authors, translators, editors, and other friends of Paper Republic to recommend notable books published in Chinese in 2019 – translations into Chinese as well as original works. The resultant list gives an insight into the titles that have made an impression this year – and perhaps offers a preview of some of the books we can hope to see available in English soon!

More…

I originally read the novel in Chinese, for a college class in Shanghai: ‘Introduction to World Literature’. The professor chose ten literary works from different languages for us to read and discuss. I remember falling in love with Rynosuke Akutagawa’s short story collection, Marguerite Duras’s The Lover and Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita. When it came to the final book, my professor handed out To Live with a broad smile, and suggested that Yu may be China’s greatest contemporary novelist. I share that view.

By Nicky Harman, December 13, '19

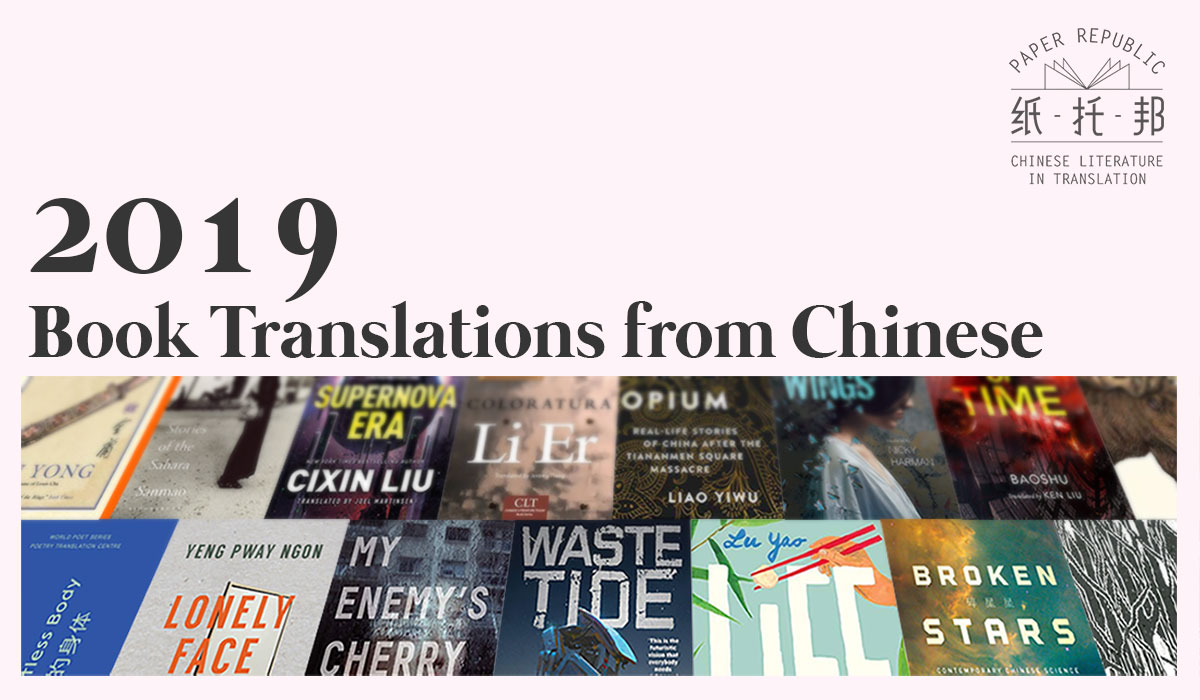

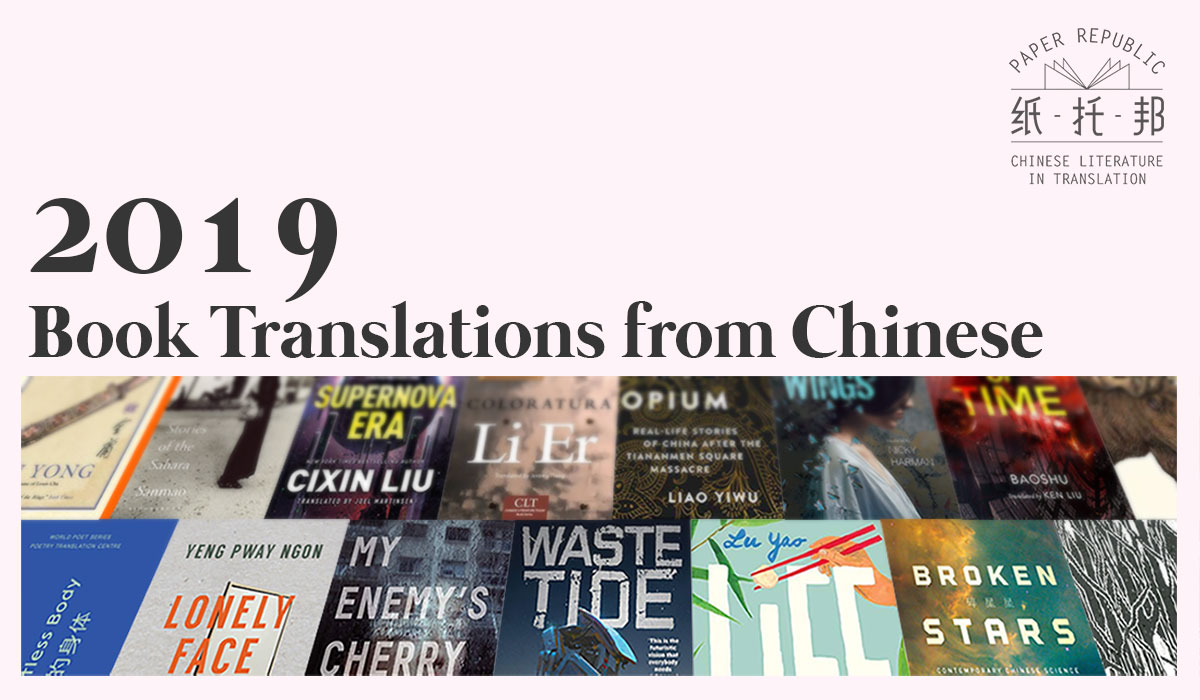

Here’s our roll-call of books translated from Chinese in 2019

There’s (almost) something for everyone this year – scifi and Singapore fiction have a strong showing, as do pre-modern classics, and even one self-help book. But still, fewer translated works were published in 2019 than in 2018 (31, as against 40-odd in 2018 ) Worst of all, only four of the list below are women writers. Every year, novels that are funny, sharp, moving and entertaining are published in the Chinese-speaking world – there is plenty for publishers and literary agents to seek out. We at Paper Republic continue to work hard to bring our favourite novels to their attention. (Watch out for our list of 2019 publications in Chinese, to be posted next week.) Read on

More…

By Bruce Humes, December 9, '19

First, it was Howard Goldblatt and his renditions of Mo Yan's novels that helped the Shandong storyteller win the (once coveted) Nobel Prize in Literature. Goldblatt has made it no secret that he edited the text in order to heighten readability.

Now, via an interview with Ken Liu in the New York Times, Why Is Chinese Sci-Fi Everywhere Now? Ken Liu Knows, we learn that translator Liu played a similar role in making Liu Cixin's The Three-body Problem popular in the West:

More…

By Nicky Harman, December 4, '19

On 29th November 2019, Paper Republic launched as a UK-registered charity promoting Chinese literature in translation. We are, as you may know, a virtual organization, with a team of volunteers spread from America to the UK and China. But to celebrate our new non-profit status, we decided to have a fund-raising party in the literary heart of London. The raffle prizes (tea, maotai, books, books and more books, signed by any of their translators who happened to be present) went like hot cakes, and the pub room was jam-packed and raucous. Inevitably, because our supporters are spread all over the world, there were some familiar faces who couldn’t be there and were sadly missed, though Eric Abrahamsen, our founder and Chair of Trustees, made a special trip over from Seattle. But now we’ve got the party bug, we hope to host more literary parties in the US and China in the near future.