Our News, Your News

By Bruce Humes, November 17, '19

The Spanish-language database here is searchable in several ways:

Title in Spanish

Original title in Chinese

Author

Translator

Genre

Entries for each of the above are also listed alphabetically, so you can scroll for a look at what is in the database even if you don't have a particular book/author/translator in mind.

It is not anywhere as complete as MCLC's one in English, but still useful.

For the English version -- supported by several pages of the Chinese original -- visit:

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/11/16/world/asia/china-xinjiang-documents.html?action=click&module=Top%20Stories&pgtype=Homepage

For the Chinese translation of the English reportage -- which appears less complete, since PDFs of the Chinese originals are not included -- visit:

https://www.nytimes.com/zh/2019/11/16/world/asia/xinjiang-documents-chinese.html

Read up, translators. This is a treasure house of translated terms that are likely to be popping up more often in Chinese writing to come . . .

We are planning to launch the first issue of Ancient eXchanges (title yet to be finalized), which will be an online journal devoted to literary translations of ancient texts. We envision the journal to be like the current eXchanges: Journal of Literary Translation, but devoted to literary translations of ancient Greek and Latin texts to begin with, and expanding to include Sanskrit, Sumerian, Classical Chinese, and other ancient languages.

By Michelle Deeter, November 9, '19

Hybrid Pub Scout, the podcast that is mapping the frontier between traditional and indie publishing, interviewed Michelle Deeter about how a book gets translated. The episode is fun and informative, and includes a book giveaway!

[Episode 32 Hybrid Pub Scout] https://hybridpubscout.com/episode-32-book-translator-michelle-deeter/

A woman impulsively decides to visit her grandmother in a scene reminiscent of “Little Red Riding Hood,” only to find herself in a town of women obsessed with a mysterious fermented beverage. An aging and well-respected female newscaster at a provincial TV station finds herself caught up in an illicit affair with her boss, who insists that she recite the news while they have sex. An anonymous city prone to vanishing storefronts begins to plant giant mushrooms for its citizens to live in, with disastrous consequences.

That We May Live includes work from:

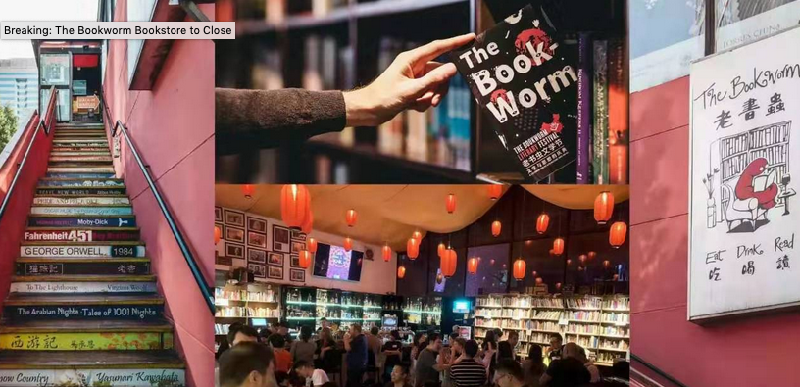

After almost two decades in the business of providing the city's book enthusiasts with food for thought, beloved Sanlitun institution The Bookworm will close its doors on Monday, Nov 11.

“Translation strategy has played a part in Murakami’s international acclaim,” says Associate Professor Kōno Shion of Sophia University. “His first English translator, Alfred Birnbaum, grabbed the attention of readers by bringing the pop image to the fore. Then, the translations of Jay Rubin, as a Japanese literary researcher, faithfully conveyed the meaning of the original text, helping to foster wider appreciation for Murakami’s writing style. Like Kawabata and Ōe, Murakami has been blessed with excellent translators. And he has always had translation in mind while writing and in his forming of a tight network with his agent and editors in the English-speaking world.”

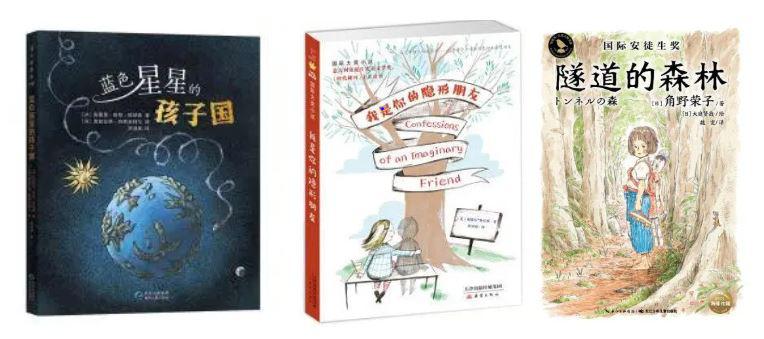

“My Favourite Children’s Books” was initiated by Shenzhen Children’s Library 深圳少年儿童图书馆 in 2014, and this year’s list was the sixth. The 2019 awards were co-organised by 39 provincial and city libraries. From January 2019, 5455 books were recommended by 129 institutions and 207 individuals. A panel of 9 experts was involved. 100,000 books were purchased and distributed to 312 schools in 39 provinces and cities across China. A total of 1,309,111 votes were cast.

A total of 30 books (2019年我最喜爱的童书30强) have been selected, 10 in each category: literature, picture books, information books.

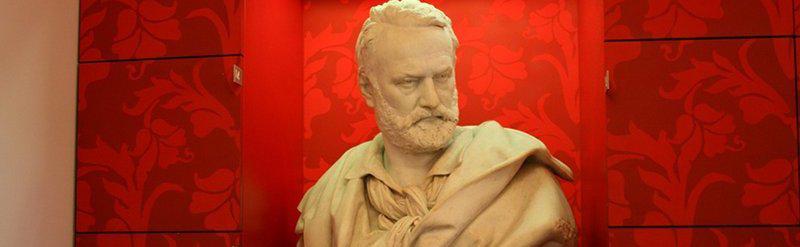

Hugo’s current prominence across the People’s Republic of China is particularly intriguing. How can a man linked to a song that has been key to anti-Beijing struggles in Hong Kong since the 2014 Umbrella Movement – one removed from Chinese music-streaming platforms – simultaneously be celebrated in China’s capital, where his many fans include Xi Jinping himself? The answer lies in the multifaceted writings of Hugo spread by globalization, relaying the struggle taking place in China and Hong Kong about what it means today to be both Chinese and a citizen of the world.

—Amy Hawkins and Jeffrey Wasserstrom

By David Haysom, November 1, '19

On Friday November 29th we’re going to be celebrating our new status as a charity with a party at the Coach and Horses (29 Greek Street, London, W1D 5DH). In addition to drinks, book talk, and a raffle, we can now confirm that Eric Abrahamsen, founder and trustee of Paper Republic, will be making a rare UK appearance! Come along to find out more about what we’ve been up to and what we have planned, and learn about the most exciting developments happening in Chinese Literature today.

Sign up now on Eventbrite to join the party.

If you can’t make it, you can still make a contribution through Paypal here (even if you don’t have a Paypal account). Everything you donate will go directly towards supporting the work we do:

- bringing the best works of Chinese literature into English

- supporting emerging translators

- maintaining the internet’s best resource for Chinese literature

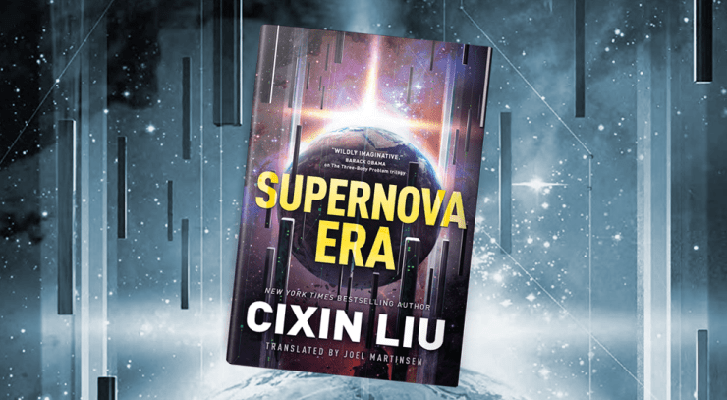

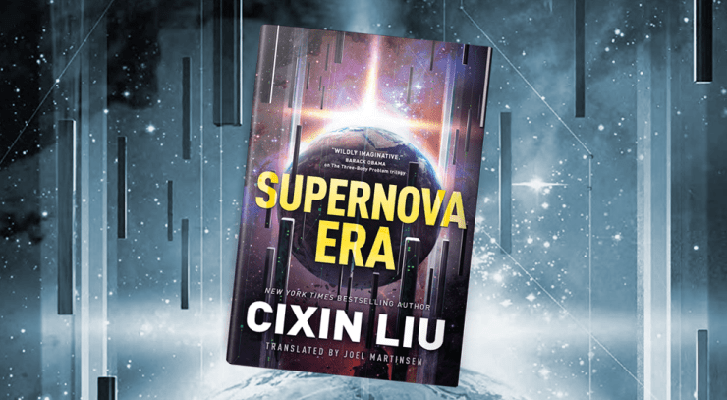

In a moment of intergenerational struggle defined by environmental protest groups like Sunrise Movement and Extinction Rebellion, and by the school climate strikes sparked by Thunberg and other young people around the globe, Supernova Era offers a tantalizing glimpse into another universe with an entirely different field of ecological politics, one where parents and grandparents won’t simply let their children and grandchildren suffer and die without a fight.

[...] the Tolkien comparison risks setting up the wrong expectations. Whereas Middle-Earth is a separate realm with its own history, mythology, peoples, literatures, and languages (however much they may echo our own histories and cultures), Jin Yong’s fantastic jianghu, full of men and women endowed with superhuman abilities accomplishing feats that defy the laws of physics, paradoxically derives much of its strength by being rooted in the real history and culture of China. The poems sprinkled among its pages are real poems penned by real poets; the philosophies and religious texts that offer comfort and guidance to its heroes are real books that have influenced the author’s homeland; the suffering of the people and the atrocities committed by invaders and craven officials are based on historical facts.

—introduction to the volume by Ken Liu

Illustration by Ye Luying

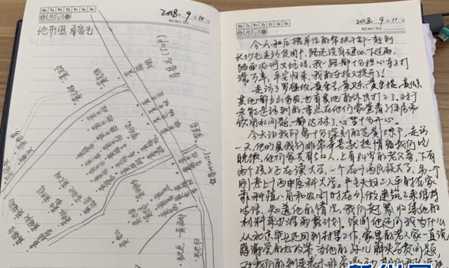

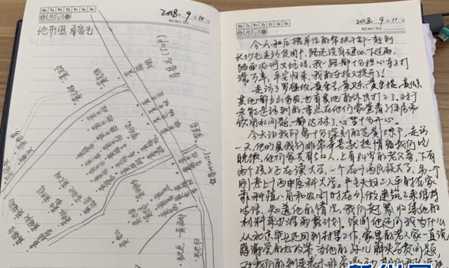

Earlier this month, Xi Jinping issued “important comments,” or zhongyao zhishi (重要指示), declaring that Huang Wenxiu (黄文秀), a young village leader in rural Guangxi who died in a flash flood on June 16, had been designated a “national outstanding CCP member” (全国优秀共产党员) by the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party — a figure to be celebrated as an exemplar for China’s younger generation.

Like Lei Feng before her, Huang Wenxiu represents the loftiest goal of life: sacrifice for the Chinese Communist Party. After earning her graduate degree in Beijing, said Xi, Huang had “given up work opportunities in the big city and resolved to return to her hometown, joining the front lines of the attack against poverty, sacrificing herself, dedicating her beautiful youth to the original mission of the Chinese Communist Party, composing a spring song of youth for the New Era.”

Her prose, which oscillates between memoir and fiction, has a laconic elegance that echoes the Beat poets. It can also be breezy, a remarkable quality at a time when her homeland, Taiwan, was under martial law in an era known as the “White Terror,” in which many opponents of the government were imprisoned or executed.

—Mike Ives & Katherine Li

The translators, Jessie and David Cowhig and Ross Perlin, have deftly captured the two registers of Liao the poet and Liao the dissident, resulting in dramatic combinations of expressive and earthy language. The raw realities of incarceration (“diarrhea-filled days in such a small space, with all those bastards, skin sticking to skin, reeking ass next to reeking ass”) abut meditations on righteousness, such as Liao’s fantasy of building a monument to China’s tens of millions of ideological criminals, each individual represented by a tear-drop shaped crystal: “Seen from a distance, it won’t look like a monument but like a mountain gleaming with the cold light of eternal tears, one piled on top of another.”

Tencent’s digital publishing platform branch, Chinese Literature, will license and release 40 Star Wars novels in the country for the first time, which will be available for free for a limited time to readers. The company will also commission an “authentic Star Wars story with Chinese characteristics”, written by Chinese Literature’s in-house author “His Majesty the King.”* According to the Weibo post, the story will “bring in Chinese elements and unique Chinese storytelling methods.”

*国王陛下

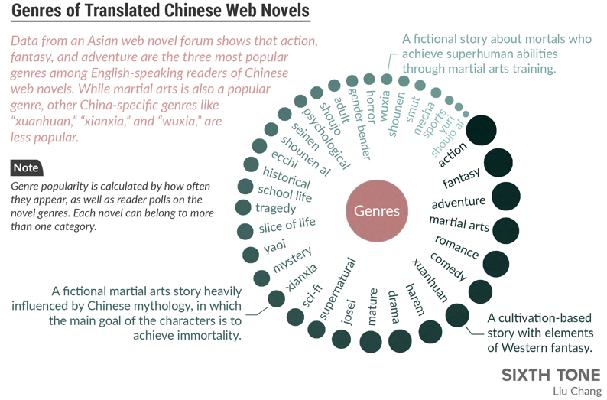

China’s tech firms are trying a variety of methods to remove the translation bottleneck. Webnovel says it has hired a team of more than 200 translators — which it pays directly — and has established a centralized glossary for frequently used terms to make sure the English versions remain consistent.

Many of these contracted workers, however, are not full-time and often struggle with the pressure of juggling two jobs. Oon Hong Wen, a Singaporean translator who signed a contract with Webnovel in June 2017, says he gets up at 6 a.m. to work for two hours before heading to the office and then continues after dinner until 1 a.m.

“Translators are just like authors,” says Oon. “Every day, we open our eyes and think about updating chapters.”

More fascinating insights into language from Michelle Deeter

By David Haysom, October 10, '19

As you may have heard, Paper Republic is now registered in the UK as a charity, and we think that’s something to celebrate!

If you’re if in the UK, we’d love for you to join us at 6.30pm on Friday November 29th at the Coach and Horses (29 Greek Street, London, W1D 5DH) to spend an evening with translators, authors, publishers, readers, and other friends of Paper Republic.

More…

By Bruce Humes, October 9, '19

The new emperor’s Belt & Road Initiative has already resulted in scores of contracts for highways, railways and port construction in Central Asia, Southeast Asia and even East Africa. Perhaps less well known is the PRC's solidly financed soft power campaign that aims to create or translate, publish and disseminate texts in the languages of the “Silk Road” peoples — land- and sea-based — that relate to the history of the ancient trade routes.

This post features the tale of Zhang Qian, diplomat and explorer of the “Western Realm” during the reign of Emperor Wu of Han (141-87 BCE). The book is in Chinese and Mongolian (traditional script) and forms part of a "Socialist Core Value" (社会主义核心价值观幼儿绘本) picture-book series for children aged 5-6.

To facilitate comparison, the blogger has provided the text in three languages, five scripts: the original Chinese and Inner Mongolian script (vertical); Hanyu Pinyin; Cyrillic Mongolian (used in Mongolia); and a translation of the text into English.

More…

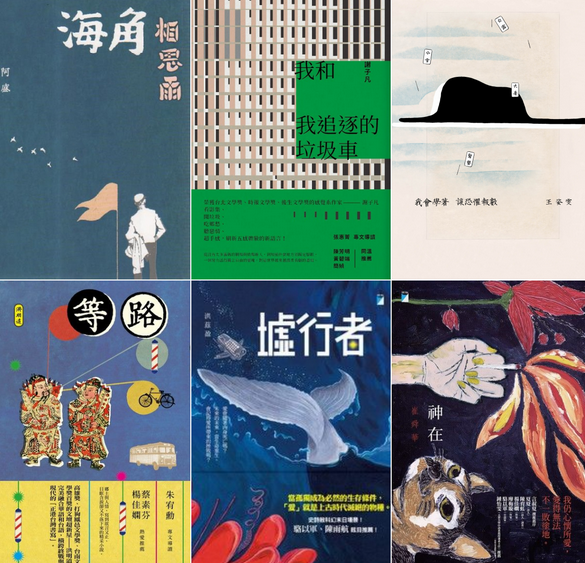

Tainan's National Museum of Taiwan Literature (NMTL) has announced that 49 out of 224 submissions have been shortlisted for the 2019 Taiwan Literature Awards.

Prizes totalling US$106,250 will be awarded.

Eight categories of admissions: Novels, book-length social reportage, short stories/essays, poetry, plays, poetry in Taiwanese, poetry in Hakka and poetry in Chinese by aboriginal writers

For details in Chinese and a PDF of the shortlist in Chinese see here

Click here for book covers and description of content in Chinese.

By Eric Abrahamsen, October 3, '19

Paper Republic has been through several incarnations during our twelve

years of operation – from the early days of translators drinking cheap

beer in Beijing, to the brainstorming session in the back room of the

Beijing Bookworm where we came up with the name “Paper Republic”, to

the first dog-slow Wordpress site. We started off as a place

for translators to talk to each other, and soon transitioned into a

platform for helping people learn about Chinese literature.

Over those twelve years we’ve done a whole lot of different stuff, almost all on a volunteer basis.

Literature database; translation services; thought-provoking blog posts; online

reading; magazine production; literary agency; publishing consulting;

publishing fellowship; literary festivals. At some point we started feeling a little dizzy, and it seemed

increasingly important to regroup a bit according to our original goals:

to bring the best works of Chinese literature into English; to support

emerging translators; and to maintain the internet’s best resource for

Chinese literature.

We realized that these goals are essentially non-profit in nature, and

that it didn't make much sense to try to run Paper Republic as a regular

company. The solution: to register as a non-profit! More specifically,

as a Charitable Incorporated

Organization, based in the UK.

We set up the charity this year. We have a great group of trustees who oversee what we do and bring us the benefit of their experience, and our management team continues to work on projects, mostly as volunteers. You can see a little more background at

our about page, and meet the gang here. If you’d like to support us via Paypal,

we’d be thrilled.

Meanwhile, a few of our more commercially-oriented projects –

Pathlight magazine, publishing consulting, and literary agency –

will go to a US company we’re calling Coal Hill Books. Feel free to

get in touch if you’d like to know more.

Lastly, if you’re in London, watch this space for an announcement of a

launch party, with wine and books and balloons and all other things

necessary for a literary get-together. We hope you’ll join us and

celebrate!

Well documented piece on how Uyghur — teaching, learning, reading and oral use — is being limited by the State.

Apparently, even compiling Uyghur textbooks that include translations from Chinese sources can be very problematic:

As a recent report from Christian Shepherd of the "Financial Times" notes in explicit detail, the Uyghur education administrator Tashpolat Tiyip and editor Satar Sawut were given suspended death sentences in 2017 for their role in creating Uyghur-language textbooks used in the only Uyghur literature class in the “bilingual” system. They, along with more than 80 other intellectuals, were charged with plotting to “secretly act to split the motherland.” A state-produced film titled "The Plot Inside the Textbooks," which was screened in classrooms across the region, accused them of sourcing much of the content of the curriculum from Uyghur literature rather than Chinese sources. Instead of sourcing 60 percent of the text in Chinese sources and 10 percent from foreign sources and then translating them into Uyghur, they had drawn nearly 60 percent of the content directly from Uyghur sources. Furthermore, using a keyword search, the word “China” had appeared only four times in one elementary school text.

By Bruce Humes, September 27, '19

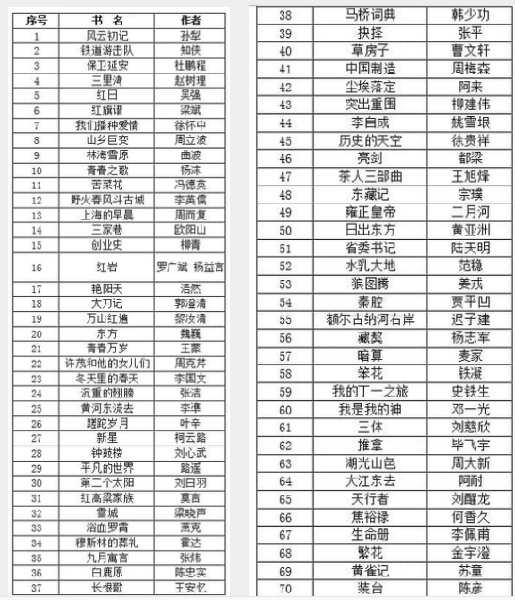

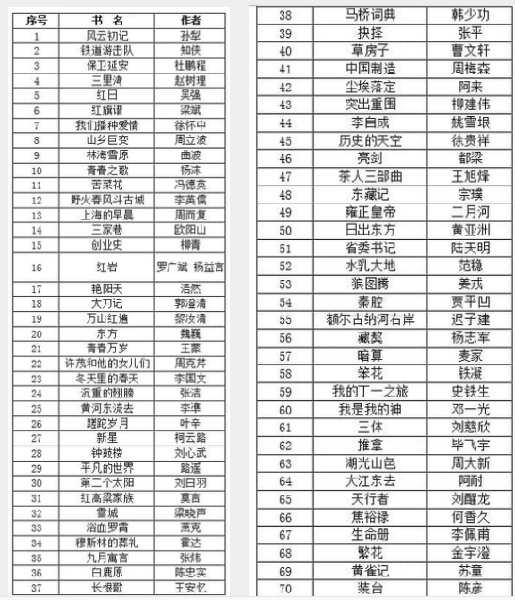

Fittingly, to celebrate the upcoming 70th anniversary of the birth of the PRC, a list of 70 post-1949 novels—“must-stock” classics for libraries nationwide, apparently — has been drawn up by the People’s Literature Publishing House and Xuexi Publishing House. See here for the Xinhua press release and full list.

Given that about one out of ten PRC citizens is identified on his or her ID card as a member of an ethnic minority, it might be interesting to scan the list for novels that classify as "ethnic fiction," i.e., a loose category (民族题材文学) that includes stories — regardless of the author’s ethnicity — in which non-Han culture, motifs or characters play an important role.

More…

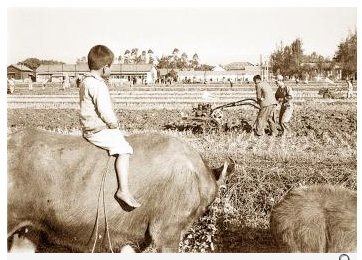

Soon the problems of people like Bright and Butterfly will be too distant, too remote from the cities where most of China's people now live. In winter, you just take bare branches for granted.....

............................

Avtar Singh is a Europe-based writer who formerly lived in Beijing. His latest novel is "Necropolis," set in New Delhi.

Mai Jia on how he deals with being the sole Chinese writer at a literary festival, and answering provocative/humiliating questions from foreign journalists.

Incredibly, PRC film censors insist that HK's Cantonese film scripts must be translated into Mandarin to vet HK films before they can be approved for screening in the Motherland, reports SCMP:

[Film Development Council's] Wong, who took the helm in April this year, said local filmmakers needed to translate a Cantonese script into Mandarin and submit it to Beijing authorities in order to screen Cantonese-speaking movies on the mainland.

Ahmed al-Saeed, CEO of Cairo-based Wisdom House Culture and Media Group, says his company is currently translating Chi Zijian's 《额尔古纳河右岸》into Arabic.

Narrated in the first person by the aged wife of the last chieftain of an Evenki clan, Last Quarter of the Moon (额尔古纳河右岸) is a moving tale of the 20th-century decline of reindeer-herding nomads in the sparsely populated, richly forested mountains that border on Russia.

The novel has already appeared in Dutch (Het laatste kwartier van de maan); English (Last Quarter of the Moon); French (Le dernier quartier de

lune); Italian (Ultimo quarto di Luna); Japanese (アルグン川の右岸) ; Korean (《어얼구나 강의 오른쪽》); Spanish (A la orilla derecha del Río Argún) and Swedish (På floden Arguns södra strand).

A How-To guide from FluentU:

1. Weibo Books

2. QiDian Books

3. Amazon Kindle

4. Loyal Books

5. Haodoo

6. 24 Reader

7. Project Gutenberg

8. Kobo

9. Pubu

Australian translator and academic Bonnie Suzanne McDougall has won a Special Book Award of China at the Beijing International Book Fair (BIBF).

-- McDougall was awarded the prize for her work developing the skills of young Chinese translators overseas as a professor at the University of Sydney, and translating books such as Letters Between Two: Correspondence Between Lu Xun and Xu Guangping (Foreign Languages Press).

-- McDougall was among 12 writers, translators and publishers from around the world to receive the award, which honours international publishing professionals who have made outstanding contributions to the promotion of Chinese literature and culture overseas. Over the last 12 years, 123 winners from 49 countries have received the award.

[For a full list of the 2019 recipients see BIBF report or Wikipedia]

Dorothy Tse’s “Cloth Birds”, translated from Chinese by Natascha Bruce

Judge’s citation: “‘Cloth Birds’ sustains a compelling tension between highly bureaucratized life and life forms resisting control: a hawker, happy people, branches shooting from tree stumps. Thanks to Natascha Bruce’s light-handed rendition, the poem is strange and ominous, and the narrative it tenuously sketches out stands in sharp contrast with the hard language of city officials and health inspectors.”

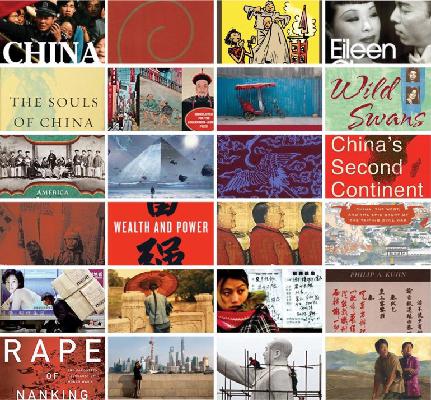

Here's the SupChina Book List, 100 books about China across all genres — fiction, nonfiction, poetry, and everything in between — ranked from 100 to 1.

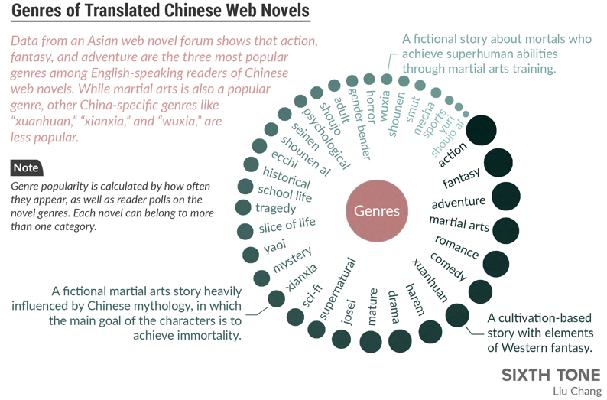

According to the 2018 China Online Literature Development Report, in 2018, the number of domestic online literary creators has reached 17.55 million, and the total number of online literary works has reached 24.42 million. A total of 11,168 Chinese online literary works has spread overseas. An increasing number of quality online literature with traditional culture genres continue to excel at overseas markets, enhancing the influence of China’s soft power.

The five winners of the 10th Mao Dun Literature Awards, with info about the authors and summaries of the books:

Chen Yan’s The Protagonist 陈彦《主角》

Li Er’s Professor Ying Wu 李洱《应物兄》

Liang Xiaosheng’s Human World 梁晓声《人世间》

Xu Huaizhong’s Story of Towing the Wind 徐怀中《牵风记》

Xu Zechen’s Northward 徐则臣《北上》

In August 1977, [Taiwan-based] writers Peng Ke (彭歌) and Yu Kuang-chung (余光中) went on the offensive against nativist literature (鄉土文學), accusing the genre’s writers of harboring communist sentiments. This turned the debate political and pushed the nativist literature war toward its high point.

Nativist literature started gaining popularity in the early 1970s and referred to a genre that sought to realistically depict the lives and sentiments of ordinary people in Taiwan, reflecting their daily struggles as well as elements of local culture and society.

Lao She’s epic Teahouse, which recounts the tumultuous first five decades of the 20th century through three generations of a Chinese family, was one of the most hotly anticipated shows at the Avignon festival in southern France.

But the new version of the saga about social injustice, hunger and corruption took a critical bashing with French daily Le Monde comparing its “over-the-top special effects” and live Chinese rap and techno music to something that one might see in a “naff stadium rock opera”.

葛浩文、林丽君教授说得好:希望 “将来英语世界的读者拿起一本翻译的中国小说尽情阅读时,是因为他们觉得这是一部优秀的文学作品,而不是因为他们想获得关于中国的某些信息。换句话讲,翻译的中国小说,应当成为一面镜子,而不是一扇窗户。”

For anyone organizing a poetry reading or other literary event, this article provides a few tips on what to do (and what not to do) as event organizer. Making the job easier for the interpreter helps ensure the success of the event. Any kind of background information is appreciated. Beginner interpreters, don't forget that you can ask for more information!

Sabina Knight on NPR's On Point program.

Broken Wings goes straight for third-rail issues, too, tackling rural poverty, human trafficking, and family planning policy. It’s a tough read, with frequent scenes of brutality, and no happy ending.

Thinking of Mulan as "Chinese" (Sinitic / Han) is like considering everyone and everything in Eastern Central Asia (ECA) (Uyghurstan / Xinjiang) as "Chinese" (Sinitic / Han), when, before about 1,500 years ago, most people in ECA were Indo-European (Tocharians, Iranians, Indians) and, after that, until quite recently (indeed, even now), most people in ECA are not "Chinese" (Sinitic / Han), but rather Turkic.

Thinking of Mulan as an overtly feminine warrior is also off the mark. Judging from the trailer, there will be plenty of fighting scenes where she looks very much like a woman. But listen to the penultimate quatrain of the ballad, which describes her meeting with her fellow soldiers after she had returned home from the war . . .

There is the romanticized view of Tibet in the West as a gentle, enlightened religious paradise, one now cruelly oppressed under Chinese rule. There is also the opposite view, formerly held by Western imperialists, that Tibet is a backwards, savage place ruled by a corrupt religion. This also overlaps with the official historiographical line in China: that Tibet before Chinese “liberation” was an oppressive feudal society. Tsering Döndrup’s vision works against all of these distorted narratives. We certainly can’t see a romantic or idealized Tibet here (the Western tourists in “Ralo” who hold such views are ridiculed), but nor is it a nightmarish, backward society. It has its (many) problems, to be sure, but his exploration of them is thoughtful and concerned, not polemical.

Waste Tide is both thrilling and thoughtful in its reflection on the environmental and human costs of global capitalism. It is set on Silicon Isle 硅屿, a homophone of Guiyu 贵屿, the real-life capital of electronic waste processing near Chen’s hometown of Shantou, Guangdong. In Silicon Isle, as in the real Guiyu, migrant workers toil in hazardous conditions to sort and recycle the remains of our smartphones, computers, and other electronics. Chen describes the scene in heartbreaking detail:

By David Haysom, July 3, '19

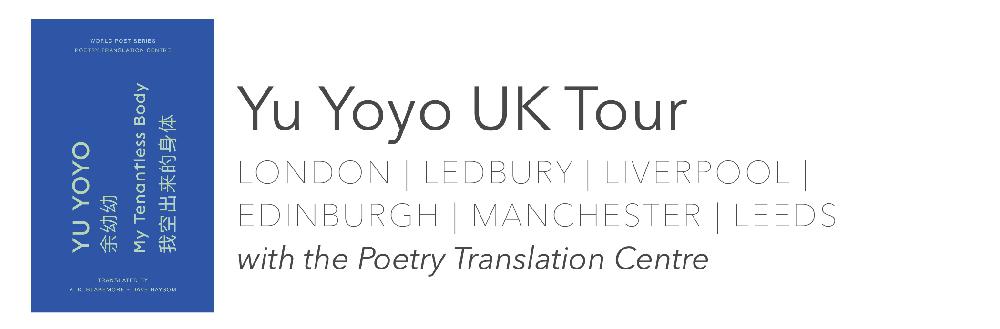

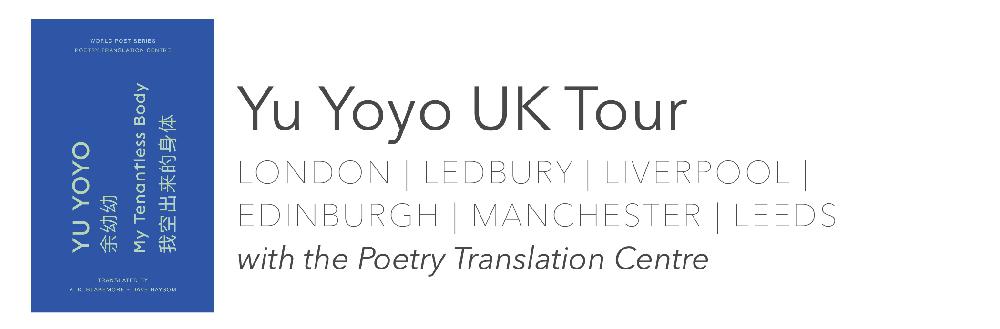

My Tenantless Body (我空出来的身体), a bilingual edition of 余幼幼 Yu Yoyo’s poetry, is available now from the Poetry Translation Centre, and this month Yu is touring the UK together with translators A.K. Blakemore and Dave Haysom:

Wednesday 3 July: Coalesce at Rich Mix, London

Thursday 4 July: Young Voices in Contemporary Chinese Poetry, Centre for New and International Writing, University of Liverpool

Sunday 7 July: Yu Yoyo and A.K. Blakemore at Ledbury Poetry Festival

Tuesday 9 July: Poetry Translation Centre Workshop on Xiao An, London

Thursday 11 July: Parallel Annotations, Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh

Friday 12 July: Contemporary Chinese Poetry, International Anthony Burgess Foundation, Manchester

Saturday 13 July: Poetry Translation Centre Workshop in Manchester

Monday 15 July: New in Translation: Poetry and Fiction in China at the Leeds Centre for New Chinese Writing

More details at the Poetry Translation Centre website

By Dylan Levi King, June 11, '19

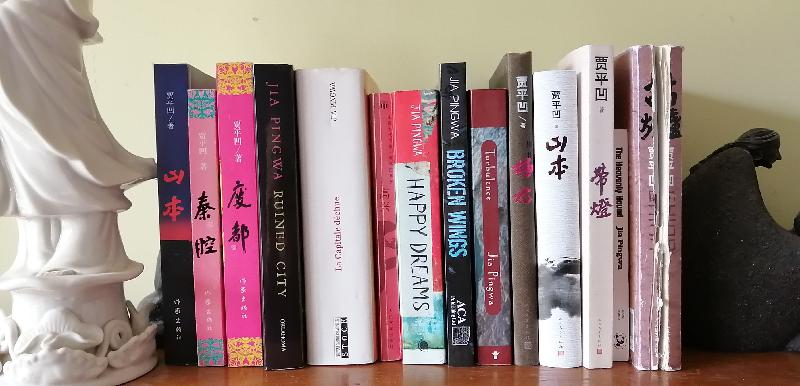

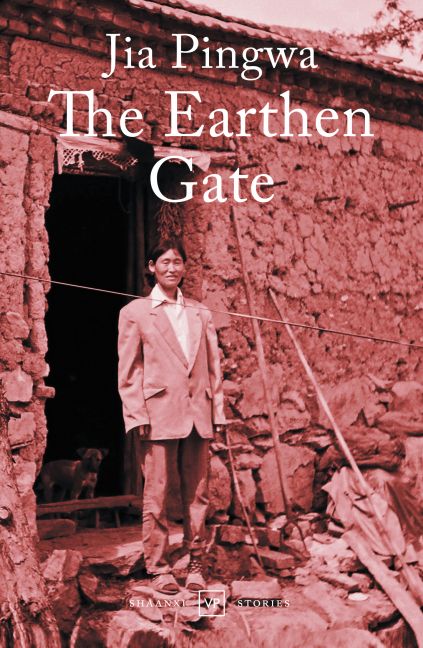

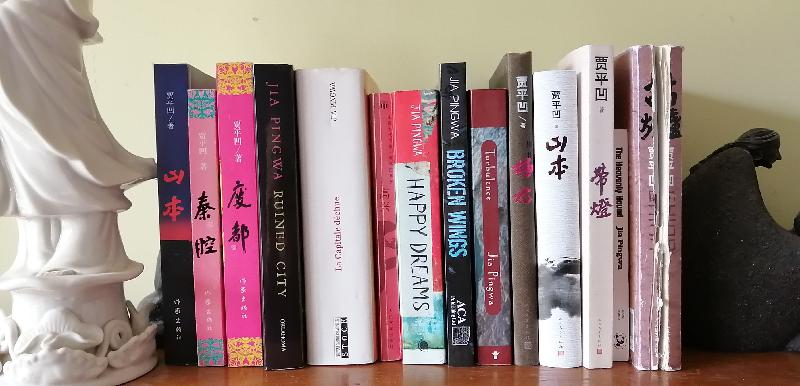

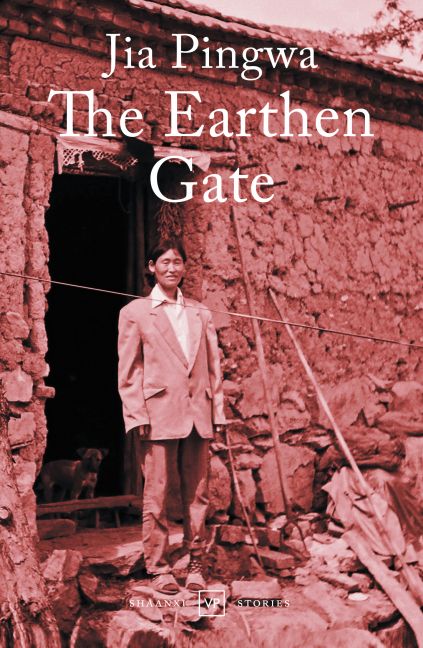

Digging into Paper Republic's archives, there's plenty of discussion of Jia Pingwa—when is he going to make it into translation? What the hell is going on?

Since 2016, five of Jia's novels have been translated, we might see two more before the end of the year, and at least three more are on the way.

The crop of Jia Pingwa books in translation have mostly been harvested from the author’s more recent works, but The Earthen Gate 土门, is the book that returned Jia to grace after the dark days that followed the ban of Ruined City 废都 in the early-1990s.

I’ve always thought that Ruined City and the three books that followed—White Nights 白夜, The Earthen Gate, and Old Gao Village 高老庄—were Jia’s best, so it’s nice to see that two have finally made it into English. The University of Oklahoma Press put out Howard Goldblatt’s translation of Ruined City in 2016, and Valley Press commissioned Hu Zongfeng 胡宗锋 of Northwest University 西北大学 to translate The Earthen Gate.

More…

The Nuosu people, who were once overlords of vast tracts of farmland and forest in the uplands of southern Sichuan and neighboring provinces, are the largest division of the Yi ethnic group in southwest China. Their creation epic plots the origins of the cosmos, the sky and earth, and the living beings of land and water. This translation is a rare example in English of Indigenous ethnic literature from China.

Translated by Mark Bender and Aku Wuwu

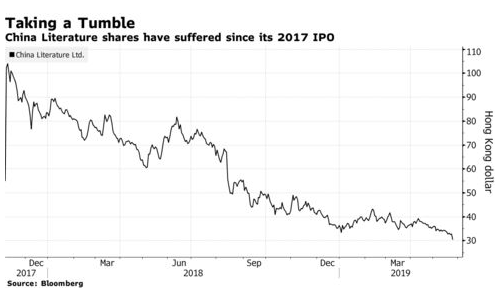

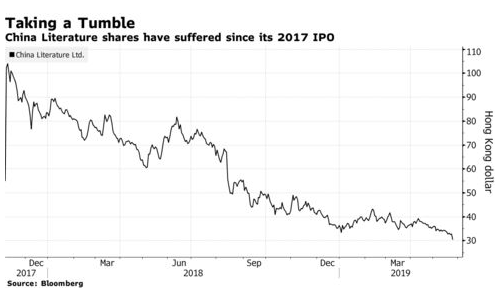

Beijing Jinjiang Networking Technology Co. was put under investigation by local authorities on Thursday for allegedly disseminating obscene information, China News Service reported last week. China Literature holds 50% of Beijing Jinjiang, according to its annual report. The Shanghai city government had ordered China Literature to clean up another website earlier that week, after it was found of spreading “vulgar and pornographic” information.

. . . there is one tricky (but very enjoyable) challenge with Tsering Döndrup’s work, and that is his tendency to use Chinese words and phrases in his fiction. Many Tibetan authors avoid this for a variety of reasons, but Tsering Döndrup is quite unique in his desire to bring this issue of language to the fore in his writing. He wants to highlight the effect that Mandarin is having on modern Tibetan, especially the fact that many Tibetans have little choice but to experience many aspects of life in modern China through Chinese. In some of his recent work he has used Chinese characters [ed. hanzi] directly in the text. In the stories in this volume, however, he renders them phonetically in Tibetan. These spellings (Tibetan has an alphabetical writing system) are of his own invention, and to all intents and purposes they come across as gibberish (imagine making up your own spellings of Chinese words in an English short story). I specialize in Chinese literature, and I still couldn’t figure out what some of the words were on my own, even when he included a Tibetan translation in parentheses.

By Helen Wang, May 31, '19

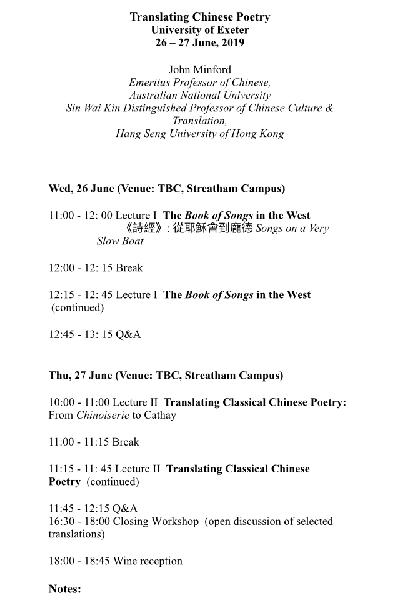

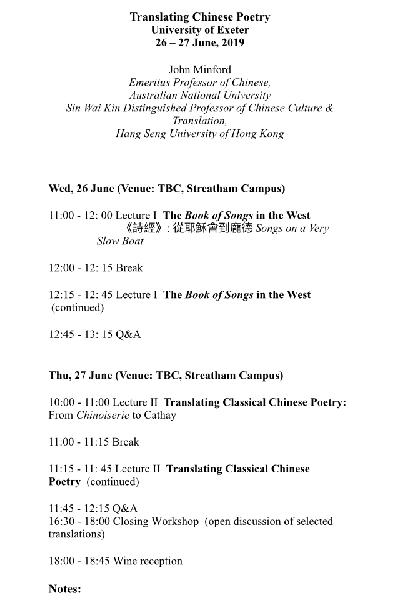

Translating Chinese Poetry - workshop with JOHN MINFORD, Univ of Exeter, 26-27 June - Free, but must register - contact Dr Yue Zhuang ( Y dot Zhuang at exeter.ac.uk)