Posts

By Bruce Humes, January 20, '21

A group of historical buildings in Taipei has been given a new lease on life and rechristened as the Taiwan Literature Base (台灣文學基地).

One of its functions: Writers in Residence Project. Hopefully, this will eventually evolve into one where translators can meet up with local authors.

Comprised of seven Japanese-style edifices, the 1,157-square meter complex used to house dormitories for Japanese officials in the colonial period before the facility was repurposed to become a hub for literary exchanges.

Taiwan generally refers to the 1895-1945 period of rule by the Japanese as 日治台灣, while on the mainland, the same period in Taiwan is often referred to using the adjective 日據.

Click here for a tour in English.

The project appears to be co-sponsored by Tainan's Literature Museum (台灣文學館), where I happily worked on translation projects 5-6 days weekly during 2019-20.

By Bruce Humes, December 13, '20

In this interview, Pema Tseden --- who writes in both Tibetan and Chinese, and is the first director to shoot a major film entirely in Tibetan --- calls for wider distribution of films that focus on China's ethnic minorites.

"Art film enriches film culture and creativity. If we don’t support it, we’ll only see movies of the same type. A vicious circle will form, wherein audiences think this is what movies are like and cinemas think audiences only accept a certain kind of movie. Ultimately, that will harm the whole industry — creators won’t persist if the market is always like this."

By Bruce Humes, November 25, '20

They are Fang Fang, author of Wuhan Diary, and Uyghur writer Muyesser Abdul'ehed (pen name Hendan Hiyal), now living overseas in Istanbul.

All 100 listed here.

By Bruce Humes, November 20, '20

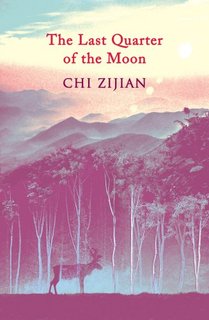

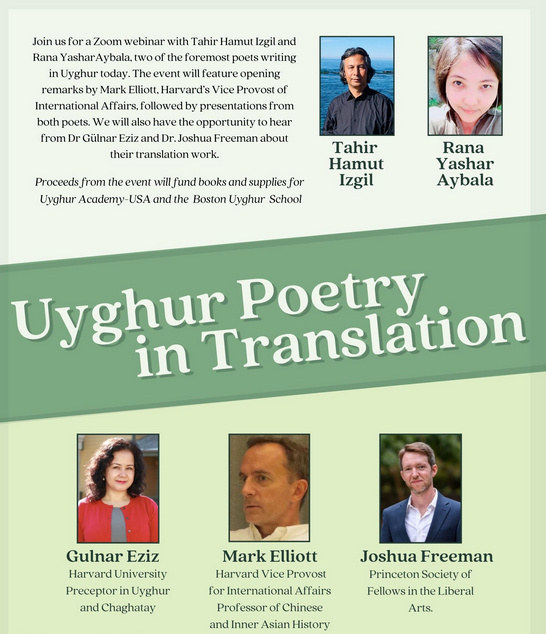

"Uyghur Poetry in Translation" live online

November 24, 2020 (12:00-13:15, Eastern Time, US)

Opening remarks: Mark Elliott, Harvard’s Vice Provost of International Affairs

Poets performing: Tahir Hamut and Rena Yashar Aybal

Translators to speak: Dr Gülnar Eziz (Harvard Preceptor in Uyghur and Chaghatay), and Dr. Joshua Freeman (Princeton’s Department of East Asian Studies)

Register here

By Bruce Humes, November 9, '20

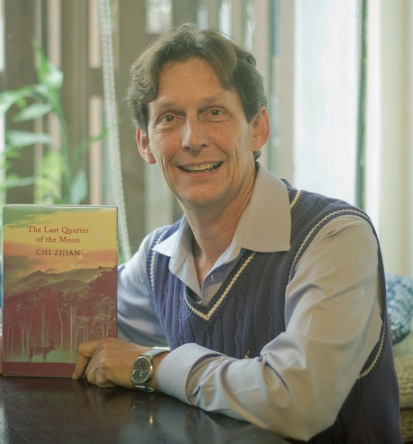

Angus Stewart recently interviewed me about translating Chi Zijian's novel that chronicles the tragic twilight of the reindeer-herding, Tungusic-speaking Evenki of northeastern China. The tale has since been translated into several languages, including French, Japanese and Swedish (see comments section for URLs).

More…

By Bruce Humes, November 7, '20

This workshop aims to explore the shifting definitions of the borderland as a territorial gateway, a geopolitical space, a contact zone, a liminal terrain, and an imaginary portal. To this end, participants will explore the intersection of ethnic, linguistic, cultural, and ecological dynamics that inform the cartography of the Chinese borderland, from the Northeast to the Southwest, from Inner Mongolia to Tibet, and from Nanyang to Nanmei.

For workshop speakers/themes, click here.

To register and receive a Zoom link, please click here.

Highlights:

Yanshuo Zhang (University of Michigan): Shen Congwen’s Idealized Ethnic: Borderland, Ethnicity, and the Spiritual Enchantments of a Modern Master

Christopher Peacock (Columbia University): “Unsavory Characters: Forced Bilingualism in the Tibetan Fiction of Tsering Döndrup”

Mark Bender (Ohio State University): “Treading Poetic Borders in Southwest China and Northeast India”

By Bruce Humes, October 1, '20

At the same time that it lays bare the ground that shaped this particular family, “Bestiary” also paints a portrait of Taiwanese identity, poking at the various histories and horrors that built the island and its citizens. A place where “Ma doesn’t measure her life in years but in languages: Tayal and Yilan Creole in the indigo fields where she was born … Japanese during the war, Mandarin in the Nationalist-eaten city. Each language worn outside her body, clasped around her throat like a collar.” From pirates to soldiers and those who came before, the men who claimed Taiwan and the women who sustained it, the country’s evolution is as much a part of the book’s collection of beasts as is the tiger spirit.

By Bruce Humes, September 17, '20

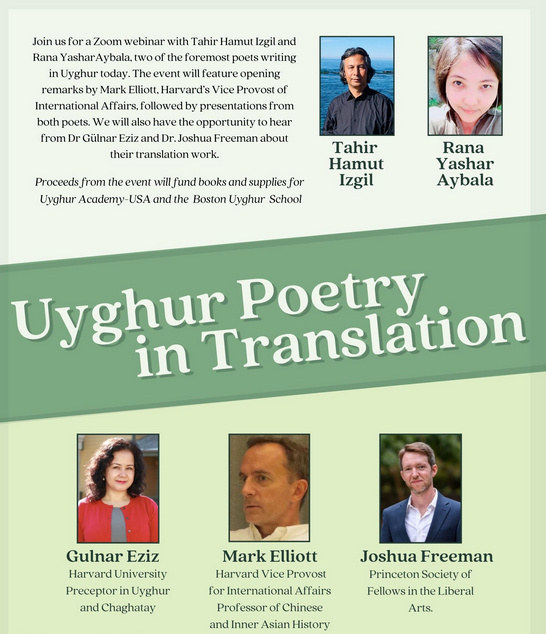

To celebrate its opening in Xi’an, Fangsuo Xi’an Creative Union (西安方所创联中心) will host a month or so of cultural forums/salons during mid-September to mid-October.

Poets Aku Wuwu (阿库乌雾) and Xichuan (西川) will appear together Sunday Sep 19 at 15:00-15:30, and Aku Wuwu will recite his long poem 《火颂》in the Yi language. Renowned Shaanxi novelist Jia Pingwa (贾平凹) is scheduled for some time during 16:00-18:00, if I interpret the poster correctly . . .

Venue: 西安市 莲湖区 星火路 22 号 老城根

G-Park 商业街区 1-F 68 商铺

For more on all the events during Sep-Oct info in Chinese visit here.

If that link downloads too slowly, you can try this one, but both are slow due to heavy load of graphics.

By Bruce Humes, August 1, '20

A few years back I posted a piece entitled A Resounding “Yes” to Mother-tongue Literature — but for Whom and about What?

(Caption: Tempête rouge --- an example of a novel translated direct from the Tibetan)

In this context, “mother-tongue” referred to indigenous languages other than Mandarin. This topic may be of interest to Paper Republicans who perceive “Chinese literature” as encompassing writing in Tibetan, Uyghur, Mongolian, as well as oral literature (口述文学) for peoples who do not have a script widely used in the PRC, such as the Evenki, Zhuang and many others.

In my essay, I posed this question: Who is going to write in their native language — or read what is written for that matter — if they cannot receive a decent education in it?

For full text --- including update on China's "bilingual" education policy in Inner Mongolia, Tibetan regions and Xinjiang -- visit here.

By Bruce Humes, May 17, '20

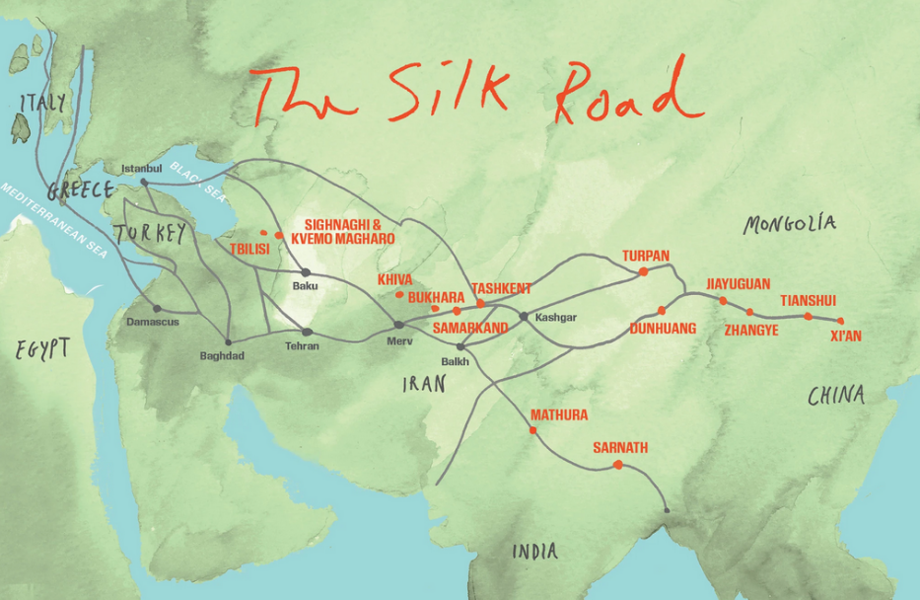

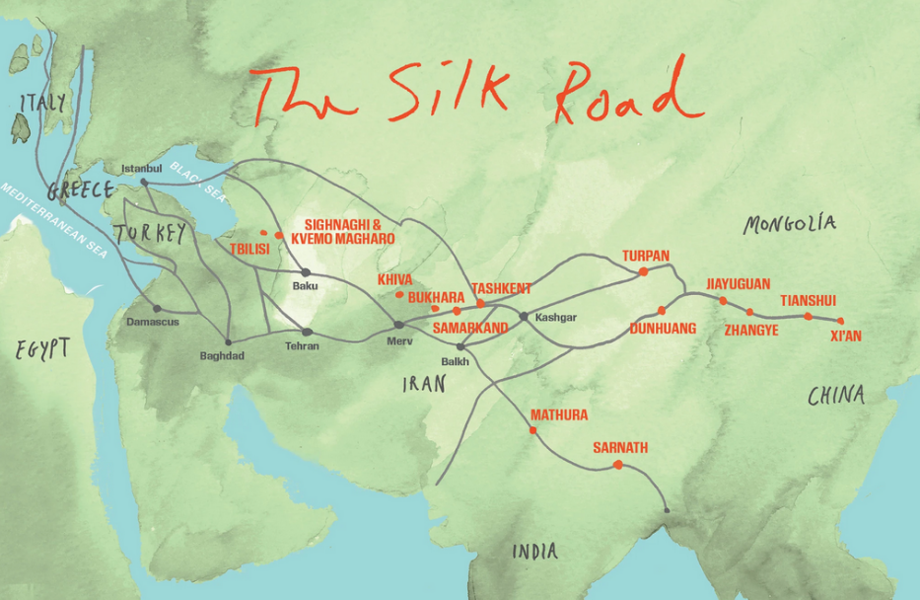

Anna Sherman’s travelogue, in which she traverses parts of the Silk Road while retracing Xuanzang’s pilgrimage from Chang’an to India, has become a major talking point on Twitter since it was published May 11.

The essay, with stunning photographs of desert sites in Gansu and Xinjiang, cites a host of Chinese poets such as Du Fu, Bai Juyi, Wang Wei and Yu Xin, as well as fiction writers Tung Yueh (The Tower of Myriad Mirrors), Pu Songling (Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio), and the Buddhist pilgrim Xuanzang (The Great Tang Dynasty Record of the Western Regions). Indeed, her piece is entitled A Poetic Journey through Western China.

A major point of controversy: Where are the Uyghurs of today, or yesteryear for that matter? In fact, they were patrons of the famous Dunhuang Grottoes whose murals often feature Uyghur culture and personages, for they were Buddhists (and practioners of Zoroastrianism and Manicheanism) before they converted to Sufi-inspired Sunni Islam.

The word “Uighur” occurs just 8 times in the 5,800-word piece, and they are described as a “minority ethnic group.” The only major reference to them is this: (Today, Xinjiang is the site of hundreds of mass internment camps, where more than a million individuals from China’s Uighur and other Indigenous ethnic groups are being held indefinitely without trial by the government.)

With the exception of Li Bai, Sherman’s main literary reference points appear to be Han writers who have been frequently (and somewhat famously) translated into English. Is this narrative simply the result of her preferences? Due to a lack of translations from other languages along the Silk Road? Or?

By Bruce Humes, April 23, '20

Ever notice that enigmatic renditions of Chinese text find their way into current China-related news?

In Missing Wuhan citizen journalist reappears after two months, one finds this closing quote:

The human heart is unpredictable, restless. Its affinity to what is right is small. Be discriminating, be uniform so that you may hold fast

Please advise: To which "Confucian" text is the author referring, and is there a better translation out there somewhere?

By Bruce Humes, April 15, '20

A number of emigrée authors are consciously choosing to write in a foreign language, rather than their mother tongue. For instance, among Chinese from the PRC, there are Xiaolu Guo in the UK and Yiyun Li in the US. Some because they believe -- rightly, I'd say -- that this will help shorten overall time-to-market. But others for different reasons.

I found this conversation between two writers, Japan's Yoko Tawada, now living in Germany and writing in German, and Madeleine Thien, daughter of a Chinese couple who moved to Canada, to be interesting from this perspective:

Madeleine Thien: When your narrator makes the leap onto the train, it’s a big leap. Maybe, in some ways, before, women in literature, when they make a big change, it must be a leap. It’s a somersault. The forces are so intense that you have to have so much propulsion to risk another life. Whereas maybe men can sort of blur from one position to another, or there’s more shading from self to self. I have the feeling that women, for a long time, if they wanted to make that jump, it was a deep cut. A break.

Yoko Tawada: Yes, that’s right. Today my friends, my male friends, do not want to go abroad or live in Europe. For a certain time, or if they’re working for a Japanese company, then it’s okay.

Madeleine Thien: But your women friends do?

Yoko Tawada: Yes.

By Bruce Humes, February 28, '20

GoogleTranslate offers translation to/from several of China's indigenous languages, the latest being Uyghur.

Others are Kazakh, Korean, Kyrgyz and Mongolian.

Turkmen and Tatar have also just joined the club -- and Turkish had long been available -- so Google Translate is doing a decent job of adding Turkic languages.

But in terms of written scripts used by a large number of PRC citizens, one stands out as missing on this list: Tibetan. It appears that its inclusion is underway, but I don't have any details.

By Bruce Humes, February 5, '20

Just got the following email from a publisher of translated contemporary Arabic literature:

Email content

Pretty impressive: One-click access to video of author speaking (in Arabic with English sub-titles) about the novel; lengthy English-language extract; background info about the author; link to publisher's blog where one can find some authors personally reading their work, etc.

Has any publisher of Chinese literature in translation done something along these lines?

By Bruce Humes, January 27, '20

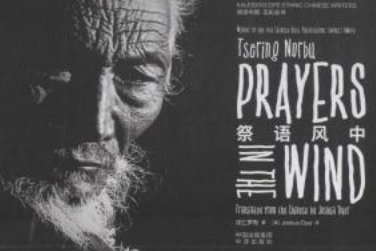

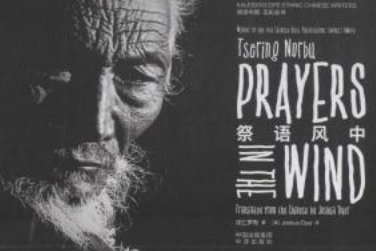

Two potentially controversial novels — one by a Uyghur author, and the other by a Tibetan — have recently been published in English. They are part of the Kaleidoscope Series of China’s Ethnic Authors sponsored by China Translation & Publishing House, a dozen or so novels by authors that highlight tales in which non-Han culture, motifs and characters play a key role (民族题材文学).

Patigül’s Bloodline (百年血脉) relates the semi-autobiographical tale of a Xinjiang native, daughter of a Uyghur father and Hui mother, who marries a Han, and struggles to bring up a family in mainstream Chinese society. Told in the first person, it unflinchingly describes her mother’s mental illness, her brother’s agonizing death from an STD and tribulations of a “mixed” marriage. For an English excerpt, visit here.

Tsering Norbu’s Prayers in the Wind (祭语风中) narrates the subsequent life of a Buddhist monk who attempts — unsuccessfully — to exit China in the wake of the 1959 Tibetan uprising and the Dalai Lama’s flight to India. For an excerpt, visit here.