Our News, Your News

By Bruce Humes, March 26, '18

Speaking at length during his recent coronation ceremony, the new emperor mispronounced the name of the Tibetan epic, King Gesar, as "King Sager" (习近平把 “格萨尔王” 说成 ”萨格尔王”).

Unsurprisingly, this news did not appear under the headline "President Hurts the Feelings of Millions of Tibetans" in The People's Daily next day.

It is significant that he mentioned two of the three ancient oral epics in his speech, King Gesar (Tibetan) and Manas (Kyrgyz). Chinese literary apparatchiks increasingly refer to them, including Jangar (Mongolian), as “China's Three Great Epics” (我国三大史诗). This despite the fact that they originated in languages other than Chinese, among non-Han peoples and in lands that were not then part of the Chinese empire.

Alerted about it via a tweet by Shawn Zhang (章闻韶), however, Victor Mair's Language Log did discuss XJP's verbal faux pas that went unreported in China mainstream media.

More…

A plot summary barely conveys the extraordinary energy of this book. It blends real and fictional characters, teems with incident – reversals, unexpected meetings, betrayals, cliffhangers – and, most of all, dwells for page after page on lovingly described combat. To paraphrase Miss Jean Brodie: for those of us who like this sort of thing, this is the sort of thing we like. As martial artists square off, evocatively named strikes are responded to with equally evocatively named parries: Search the Sea, Behead the Dragon; Seize the Basket by the Handle; and, only to be used in extremis, the desperation move: Sword of Mutual Demise. The novel gives us the history of strange martial techniques, assesses the merits of different schools of kung fu, and describes the mysterious internal alchemy that gives rise to the most devastating physical force.

您怎么看翟理斯和韦利对诗歌翻译的争论?还有韦利和庞德的争论?诗人翻译和学者翻译的永恒战争有没有和解的可能?

温伯格 [Weinberger]:一种翻译既有来处也有去处。大多数学者翻译的问题是译者知道原文的所有涵义,但却不知道译文要去哪里——也就是目标语言的当代文学语境。在中国诗歌的汉学家译者中,有三位伟大的例外:韦利、华兹生,还有最近的大卫·辛顿(David Hinton)。他们是绝无仅有的译出了伟大英语诗的学者,因为三位都是他们时代英语诗歌的专家。(葛瑞汉可以算第四位,不过他只译了一本诗集。)值得注意的是,他们也都受到了那些只通些许中文的诗人译者的巨大影响,比如庞德、王红公、加里·斯奈德(Gary Snyder)等等。

The Stolen Bicycle (單車失竊記), a novel written by Taiwanese author Wu Ming-yi (吳明益) and translated into English by Darryl Sterk, has been selected to contend for the prestigious Man Booker International Prize.

The novel is about a writer who embarks on a quest in search of his missing father’s stolen bicycle.

Pen America's report looks at a variety of questions, including the impact of social media censorship on China's fiction writers. Here's an excerpt:

Case Study 3: Chinese Novelist Murong Xuecun

Murong had 8.5 million followers on his Weibo microblog accounts before they were shut down. He attempted to set up new accounts, which were repeatedly shut down as well. The effort of continually trying to evade the censors, Murong shared with PEN America, eventually “wore him out.” Supporting himself with his writing might have been possible if he had continued to toe the Party line through self-censorship. But having made the choice to speak out, Murong’s once-promising literary career is on indefinite hold.

“I sell fresh fruit online and deliver the fruit to my customers now,” he said. “My online store is called ‘Murong Mai Gua’ (Murong sells melons). I am working on my next novel, but I don’t know if it can be published. Four years ago, all my previously published books were pulled off bookstore shelves and I lost the ability to make any money from writing in China,” he told PEN America.

這是一次全中國都看到了的翻白眼。

The country’s media regulator – the State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television – was set to merge with the Ministry of Culture to create a super cultural ministry to expand the scope of China’s ideological influence, a source familiar with the discussions told the South China Morning Post.

Both bodies are overseen by the State Council, and the merger is expected to be part of a sweeping structural overhaul of the Communist Party and state bureaucracy to be unveiled during the National People’s Congress in Beijing on Tuesday.

By David Haysom, March 3, '18

The Beijing Bookworm Literary Festival is back, with a great line-up of events featuring international authors and some of our favourite local writers, including Xia Jia, Murong Xuecun, Ren Xiaowen, Sun Yisheng, and many more! Pathlight will also be represented at a translation workshop in collaboration with Spittoon magazine.

By Nicky Harman, March 1, '18

Chen Xiwo has some very interesting things to say about his short story 'Pain,' from his collection in translation, The Book of Sins, in a discussion on the Los Angeles Review of Books, with his publisher Harvey Thomlinson, LARB's editorial team, and me, Book of Sins translator.

By Nicky Harman, March 1, '18

I was asked to produce a list of the ten best novels in translation for the China in Context book festival weekend, which focusses this year on translation. I managed to slip "of the" into the title, and have emphasised it's a very personal list. And I guess any publicity (for Chinese literature) is good publicity!

Chinese media report that prolific Xi’an-based novelist Hong Ke (红柯), who was long captivated by the multiethnic history of Xinjiang, died on February 24, 2018 (突发: 陕西著名作家红柯去世享年56岁).

He left his native Shaanxi for Xinjiang in 1983 and lived for a decade in the Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture bordering on Mongolia and Russia. Although he returned to Shaanxi and took up university teaching positions in Xi’an, Hong Ke --- a Han who never mastered any language but Mandarin --- was deeply inspired by the cultural fusion he discovered in China's far northwest, and subsequently penned numerous novels and short stories set in Xinjiang that feature historical and legendary characters from China's various ethnicities. See here for his Chinese novels, here for an English excerpt from one of them, Urho (乌尔和), and here for excellent backgrounder on him in French.

“A Hero Born” is the first of the 12 volumes of “Legends of the Condor Heroes”, written in the late 1950s. Set in the years after 1205, it enjoyably wields the weapons of wuxia -- traditional martial-arts fiction, with its spectacular combat and pauses for philosophy -- to show Chinese identity under threat from foreign and domestic foes. “Three generations of useless emperors” have brought the Song dynasty to its knees. Quisling allies of the Jurchen Jin invaders, who rule the north, abet imperial decline.

Enter the dragons of salvation: an “eccentric” kung fu clan known as the Seven Freaks of the South, and the militant Taoist monks of the Quanzhen sect. They are first rivals, then collaborators. Though strained, their joint mission embodies a pact between “physical force” and the “more enlightened path” of wisdom that may rescue China.

The novel [The Stolen Bicycle] shows us the talent but also the personality of the novelist: his obsession with ecology is obvious as his passion for bicycles; he even toured Taiwan on an old collector’s bike to promote his novel! A specialist of butterflies, the novelist evokes the industry around them and collages made with their wings.

His family is a central theme and there are many references to the Chunghua Shopping Center where the family worked and lived. Finally, as in other books, he immerses us into the history of Taiwan, Japanese colonization and aboriginals but underlines: “I did not write this novel out of nostalgia but out of respect for an era I did not experience."

Nevertheless, the unifying theme of the novel is the search for a lost father whom the narrator hopes to find by his bicycles which were stolen or lost or abandoned.

(The book is reviewed in both French and English)

LiT Program residencies are an exceptional opportunity for international writers and English-language translators to create new work individually and in collaboration, to find a wider audience for contemporary writers through translation, and to participate in literary exploration and cultural exchange as members of the global creative community at VSC.

From The Metropole, 8 Feb 2018.

By Kristin Stapleton, a member of the board of directors of the Urban History Association and of the Global Urban History Project. She teaches history at the University at Buffalo, SUNY. Her research focuses on urban administration in China and representations of cities in Chinese fiction. She is the author of Fact in Fiction: 1920’s China and Ba Jin’s Family

By Helen Wang, February 4, '18

In 2016 Minjie Chen, Anna Gustafsson Chen and I started a blog/web-resource Chinese Books for Young Readers. We just posted our 60th piece. Thanks to everyone who has helped us along the way. Keep following!

-- See the full list with weblinks here

U.S. publishers cross borders to import more children’s books from China, as Chinese publishers create contemporary stories. - a long article by Karen Springen (paywalled)

Whenever I translate, I first read the original text carefully and internalize the ideas as clearly as I can, letting them slosh back and forth in my mind. It’s not that the words of the original are sloshing back and forth; it’s the ideas that are triggering all sorts of related ideas, creating a rich halo of related scenarios in my mind. Needless to say, most of this halo is unconscious. Only when the halo has been evoked sufficiently in my mind do I start to try to express it—to “press it out”—in the second language. I try to say in Language B what strikes me as a natural B-ish way to talk about the kinds of situations that constitute the halo of meaning in question.

Fiction bestsellers in China last year were dominated by non-Chinese authors, according to OpenBook, while homegrown authors sold better in nonfiction.

As nationalism continues to influence American politics, the National Book Awards adds a category for translated literature with ‘the power to touch us as American readers.’

Guidelines for censorship in the Xi Jinping Era have tightened considerably for all, be they bloggers, reporters or novelists, but for minority authors who wish to highlight the culture or challenges facing non-Han peoples within today’s PRC, the obstacles to publication and the list of “unmentionables” is even longer. Aside from a shortage of translators working from indigenous languages into Mandarin or foreign languages, there is also the subtle impact of state- and self-censorship that ensures certain “ethnic realities” are rarely depicted, be it in a magazine, book or online, in reportage or even fictional form. A Uyghur businessman who tries to book a room in Shanghai may be informed the hotel is full, or face interrogation from a policeman; a community of Mongolian herders may be conveniently classified as “ecological migrants” (生态移民), given negligible compensation and forced to relocate, in order to make way for a profitable mining project or power plant; and a rural Tibetan dweller may be refused entry to Lhasa, home to innumerable sites sacred to indigenous Buddhists, because he lacks a travel permit to enter the administrative capital of the Tibetan Autonomous Region.

Such real-life phenomena are contentious and perceived by the authorities as likely to breed “inter-ethnic” discontent, and when mentioned in literary works or reportage are heavily redacted or simply not published. Very occasionally, however, a minority author — as in the excerpt below — manages to skirt the censors and turn the spotlight on burning issues.

Congratulations to Aili Mu, with Mike Smith, for their book Contemporary Chinese Short-Short Stories: A Parallel Text (Columbia University Press, 2017)

- see which short stories were chosen here

“Somewhere in…” is a monthly column from the Global Literature in Libraries Initiative that addresses international censorship issues.

By Eric Abrahamsen, January 24, '18

Pathlight Magazine, a Paper Republic publication, is looking for a new

Managing Editor!

The position is about half time (though sometimes busier than others),

and based in Beijing. You will be working together (mostly remotely)

with Paper Republic editors, and with People’s Literature Magazine,

our Chinese partners. Responsibilities include:

- Keeping the magazine to a quarterly publication schedule.

- Working with Paper Republic and People’s Literature to

collectively choose a theme and a table of contents for each issue.

- Assigning and collecting translations.

- Editing translations, or assigning editing work to other editors.

- Doing social media promotion.

We’ll provide translator and editor resources, and help connect you

with everyone you need to talk to.

Salary is paid per issue, and is competitive.

Our ideal candidate:

- Is in Beijing.

- Is a Chinese => English translator. One of the strengths of

Pathlight is that our translations are edited by translators.

- Is organized, and not afraid to crack the whip.

- Is conversant with contemporary Chinese fiction and poetry.

- Has some familiarity with digital publishing, including using

InDesign and manipulating epub files.

- Has a bit of experience dealing with Chinese government-owned

institutions.

- Would be available to start in the next couple months.

Interested parties please email info@paper-republic.org.

By Eric Abrahamsen, January 16, '18

Spurred by Three Percent's new searchable database of translations, in particular the ability to add new or missing titles, I've finally gotten around to finishing the first version of a similar "suggestions" function for the Paper Republic database of translated Chinese literature.

You can find the "Suggest an addition" link on the left-hand side of the PR pages, or follow this link directly. Right now it's limited to suggesting works of literature (though there's a write-in field for authors who aren't in the database), but I hope to eventually expand the options. If you're adding new works of literature to the database, please remember that Chinese originals and English translations have equal standing, so make two suggestions.

And thanks! If you have any suggestions about the suggestion (meta-suggestions!), please leave them in comments on this post.

By Nicky Harman, January 14, '18

In-depth article about Jia Zhangke and the Pingyao film festival, including a mention and still from Han Dong's debut A Night at the Wharf [《在码头》] (Han Dong directed, Jia Zhangke produced): https://www.filmcomment.com/article/jia-zhangke-pingyao-film-festival/

203: Books reviewed in 2017

Number of reviewed books by country of author (51 countries in total):

- France 27.5

- Japan 26

- US 20.5

- UK 16

- Italy 10

- Spain 10

- Russia 8

- India 6

- Romania 5

- Belgium 4

By David Haysom, December 30, '17

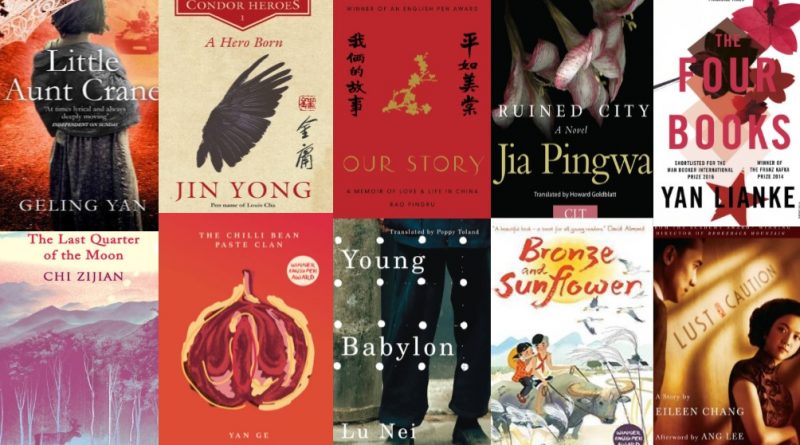

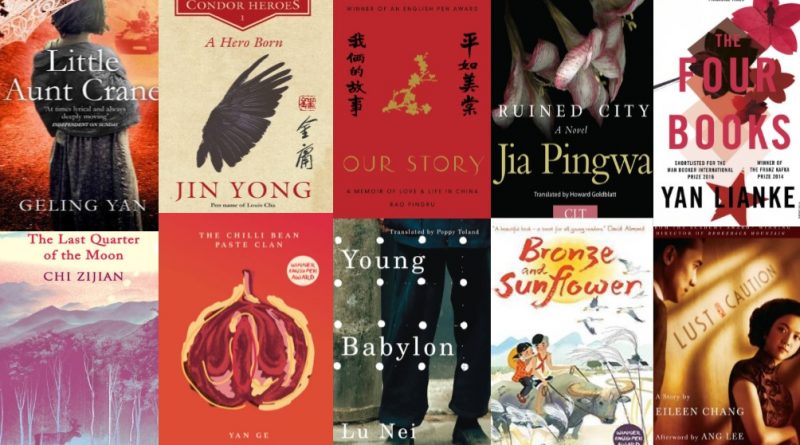

Which new works of sci-fi were worth reading this year? Whose new novel forged a new way of representing dialect in fiction? Why are Chinese authors reading the critic James Wood? What did the daily life of a Communist guerrilla in 1980s Malaysia look like? Find out in our list of new books released in Chinese in 2017, as recommended by Paper Republic and friends!

More…

By David Haysom, December 30, '17

Which works of sci fi were worth reading this year? Whose fiction has forged a new way of representing dialect in literature? Why are Chinese authors reading the critic James Wood? And what was life like for Communist guerrillas in the jungles of 1980s Malaysia? Find out in our list of the best books published in Chinese in 2017, as chosen by Paper Republic and friends!

More…