Posts

By Dylan Levi King, October 19, '20

In China in Ten Words, Yu Hua describes stubbing his toe on stacks of Lu Xun books gathering dust in the office of a provincial cultural center and saying to himself, "'That guy's days are over, thank goodness!'" (this is from the translation by Allan H. Barr).

As Yu Hua puts it, Lu Xun went "from being an author to being a catchphrase and then back again." Lu Xun’s legacy was flattened in the long half-century after his death. When state control over literature loosened on both sides of the Straits in the ‘80s, attempts were made to reinflate the flattened Lu Xun, but perhaps the damage was already done.

What changed Yu Hua’s mind was picking up the collected short fiction after a director pitched him on writing a script based on some of Lu Xun’s stories.

It made me think back to those books of his under the table in the cultural center, and it seemed to me now that they had been trying to tell me something. When they tripped me up as I went in and out of my office, they were actually dropping a hint, quietly but insistently signaling the presence of a powerful voice within the dusty tomes.

I always found the veneration of Lu Xun understandable, and I appreciate his contributions to contemporary Chinese literature, but I found it hard to see much vital and pressing in his work. Matt Turner’s translation of Lu Xun’s Weeds was a minor revelation last year.

More…

By Dylan Levi King, August 2, '20

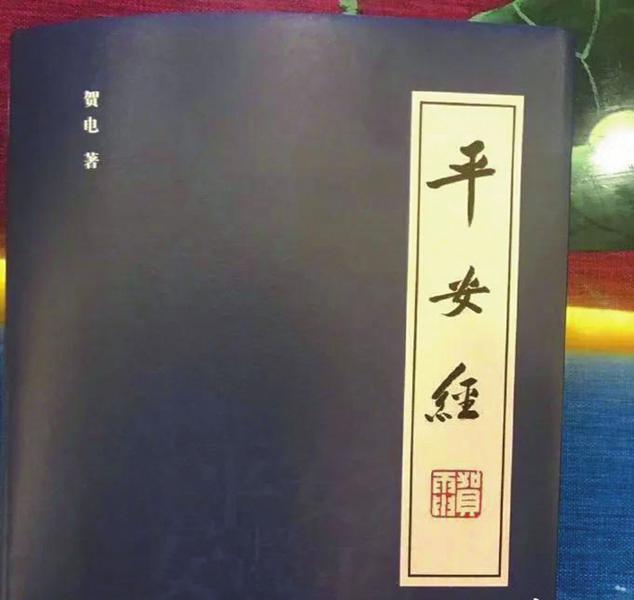

The biggest story in Chinese literature this week is a book called Peace Mantra (or Peace Sutra, Classic of Peace—however you want to translate Ping’an Jing 平安经), written by He Dian 贺电, an officer with the Public Security Bureau in Jilin.

The South China Morning Post's Liu Zhen describes Peace Mantra like this: “The 336 pages of the book are covered only with variations of the sentence: ‘Let … be safe.’”

Let the train stations of China be safe

Let Beijing Station be safe, let Xi'an Station be safe, let Zhengzhou East Station be safe, let Shanghai Hongqiao Station be safe, let Hangzhou East Station be safe, let Guangzhou South Station be safe, let Nanjing South Station be safe, let Chengdu East Station be safe, let Beijing South Station be safe, let Tianjin West Station be safe, let Wuhan Station be safe, let West Kowloon Station be safe, let Hsinchu Station be safe.

An introduction explains: “The world needs peace. The nation needs stability. All industries require safety. The people yearn for tranquility.”

When news of the book and He Dian’s extensive promotion spread to social media, it was mocked and condemned. State media joined in with editorials.

It seems clear that there was some funny business. The book was priced at 299 RMB ($42 USD), which doesn’t sound that bad, but puts it at a price point about six or seven times what most books sell for. There were symposiums held to discuss it, and there were public readings.

More…

By Dylan Levi King, July 13, '20

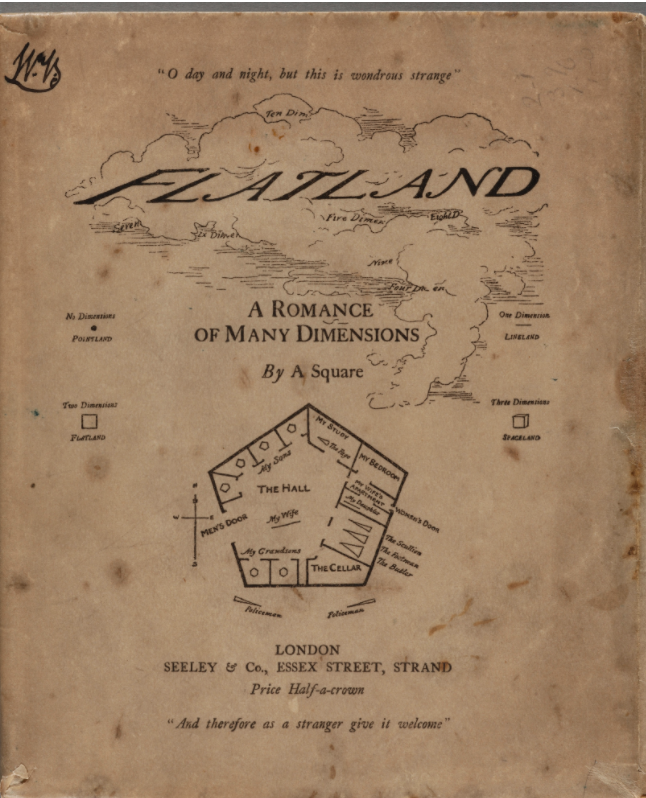

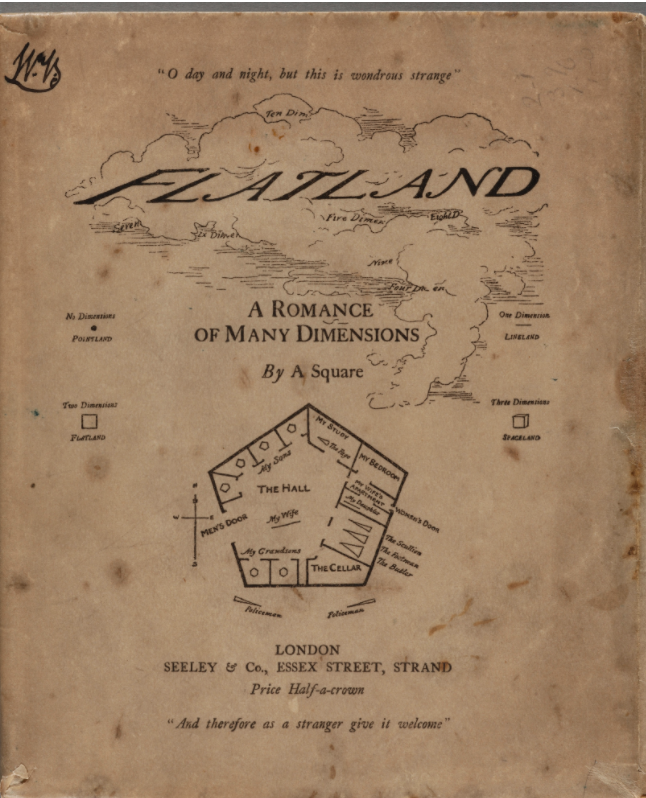

"Sinophiles between Flatland, Fetish, and Feuilleton":

Despite (or because of) the increasingly fraught relationship between the Chinese- and English-speaking parts of the world, to my eyes anglophone Chinese studies today finds itself blessed with a wealth of voices, both within academia and without. Projects like the ever-excellent Chinese Storytellers newsletter, for example, highlight the all too often overlooked contributions of Chinese and Chinese American journalists to the political and social discourse; Reading the China Dream fills out the picture with an angle on the intellectuals; Neil Clarke and his merry band of pranksters over at Clarkesworld continue to bring much needed attention to Chinese science fiction (in addition to that of other languages); or Paper Republic (as of last year, a registered charity in the UK!) and the Leeds Centre for New Chinese Writing, which do the same for Chinese language fiction more broadly.

By Dylan Levi King, July 12, '20

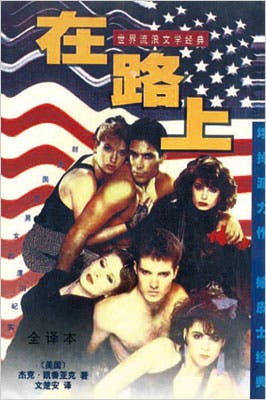

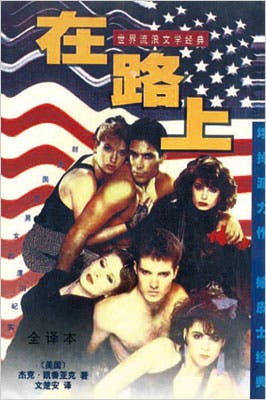

A short time ago, the Paper 澎湃 ran an interview with Tao Yueqing 陶跃庆 about his work on On the Road, in which he explains what it teaches us about America, the afterlives of the book, and how gave up on translation for a day job. (《在路上》译者陶跃庆:凯鲁亚克及其燃烧的时代.)

I’ll admit, I am jealous sometimes of our Chinese comrades. I understand it’s not glamorous work (it’s my job!), but a book like On the Road is not waiting out there for me—a book the publisher has to hustle to get it into a second, third, fourth printing, a book appearing in the rucksacks of disaffected urbanites for the next two decades, a book that I will be interviewed about thirty years later...

Tao Yueqing had no idea that he had just helped launch an American classic in Chinese translation. He took his half of the manuscript fee and went on with the rest of his life.

More…

By Dylan Levi King, May 17, '20

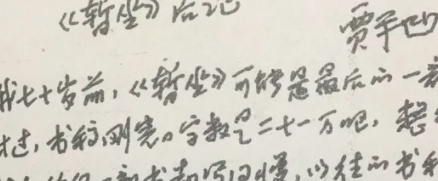

When Nicky Harman and I received Jia Pingwa’s invitation to visit him in Xi’an last spring ("Jia Pingwa's Hometown"), apart from being mobbed by fans at an opera performance and shepherded through a tour of Xi Zhongxun’s old cave home by enthusiastic local bureaucrats and Party functionaries (many not even born when Jia’s literary stardom reached its first peak in the early 1990s), the most surreal experience was poking around his writing desk. The desk itself is obscured completely by towers of books. To get to the chair he sits at to write, which is draped with fur, you need to be slim enough to slide between two walls of stacked up novels, reference manuals, works on local customs history books, and volumes of poetry. The available work area on the desktop is also limited—there are too many books piled up, and there has to be room for a carton of cigarettes and an ashtray, too. When we visited in the spring, the small amount of available work area was covered in pages from a novel that he was writing—black felt-tip pen on white pages, longhand—a biscuit tin (for completed pages), and left open beside it, a book of Eileen Chang short stories.

He told us that it would be an urban novel.

That would make it his first extended return to the city since Happy Dreams 高兴 in 2007 (it’s a book he doesn’t consider an urban novel, since it concerns migrant workers from the countryside).

Of course, his novels are invariably never about just the city or just country, but about the tension between them, characters trapped perpetually in between. The idea of an extended return to the city, though, years on from urban novels like White Nights 白夜, was intriguing.

When I returned late last summer for the 29th China National Book Expo ("迪兰先生, world famous Sinologist / 第29届书博会"), Jia was talking publicly about a city book, for which he was still working on final drafts.

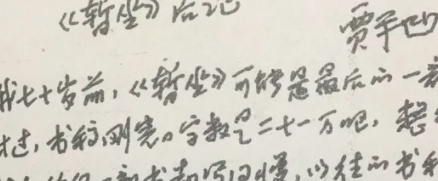

The novel (or perhaps novels) will be published by the Writers Publishing House 作家出版社 in July, and some lucky people have already gotten their hands on it, but the Jia Pingwa Research Institute 贾平凹文化艺术研究院 earlier today posted the afterword of the announced novel:

贾平凹:长篇小说《暂坐》后记

The Jia Pingwa afterword is almost a genre in itself. It's the reason why Jia's novels are best started from the rear—you need the afterword to explain what you're about to read.

In the afterword to Sit Awhile 暂坐, Jia explains that the germ of the novel was a tea shop in his building, where he drank tea twice a day, and his observations of the peculiar world of the owner and the women that drifted through. He writes in this novel about women, mostly, he says, because he lacked confidence. “I found myself no longer writing the women, but the women writing me.”

It makes sense now why he might have been referring back to Eileen Chang’s short stories. I quite like the idea of Jia Pingwa attempting a Chu T'ien-wen-style novel about the interconnected lives of urban women.

Earlier this year, I wrote about the Nicky Harman's masterful translation of Jia's Broken Wings 极花 for ACA ("‘Broken Wings’: Jia Pingwa’s Controversial Novel Explores Human Trafficking And Rural China"), and noted the sharp criticism that followed its original publication, with the author branded a male chauvinist. On the contrary, I've always found Jia's women characters mostly sympathetic and—in recent books, at least— usually rendered with more care than his male characters. But it will be interesting to see if the critics that appeared for Broken Wings will pop up again.

By Dylan Levi King, March 10, '20

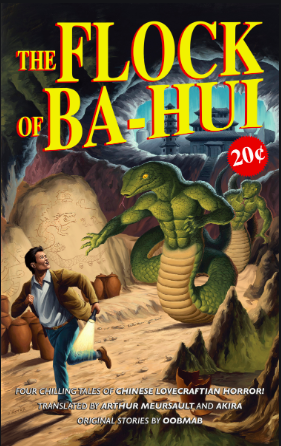

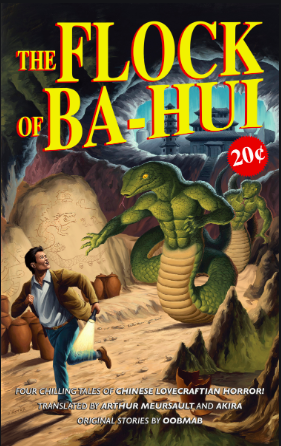

The Flock of Ba-Hui and Other Stories from Camphor Press, a collection of Lovecraftian horror by a pseudonymous author is among the more interesting works to appear recently in translation from Chinese.

Of course, web novels and online writing have made it into translation before. I’m thinking of Shen Haobo 沈浩波, who made a name from poems published online (and who once made a living as a publisher of online lit), and also Murong Xuecun 慕容雪村, whose Leave Me Alone was first posted online—some of that has made it to ink and paper, but most of the translation of web stuff remains online, and it’s mostly in the form of light novels, like Godly Stay-Home Dad 神级奶爸 and the nearly 5000 chapter Martial God Asura 修罗武神 (it could be 10,000 chapters by now).

I’ve pulled examples from two extremes—work mostly of interest to academics on one side, wildly popular wuxia fantasies on the other—but the stories in The Flock of Ba-Hui probably sit somewhere in the middle: still genre fiction but from a slightly more serious tradition, and written with more attention to the craft. They were culled from the Ring of Wonder, a discussion board for fantasy worlds, games, and literature.

More…

By Dylan Levi King, June 11, '19

Digging into Paper Republic's archives, there's plenty of discussion of Jia Pingwa—when is he going to make it into translation? What the hell is going on?

Since 2016, five of Jia's novels have been translated, we might see two more before the end of the year, and at least three more are on the way.

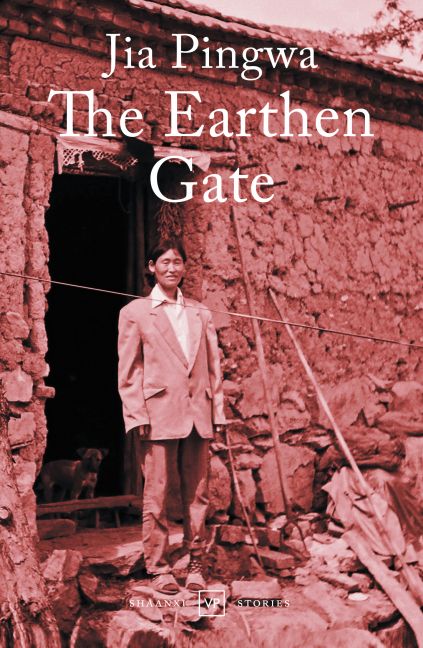

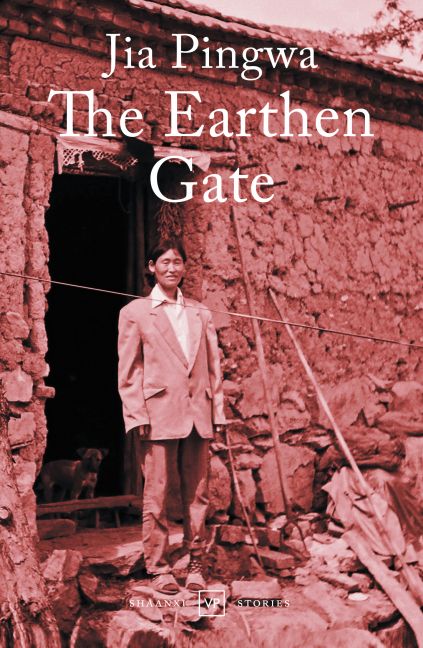

The crop of Jia Pingwa books in translation have mostly been harvested from the author’s more recent works, but The Earthen Gate 土门, is the book that returned Jia to grace after the dark days that followed the ban of Ruined City 废都 in the early-1990s.

I’ve always thought that Ruined City and the three books that followed—White Nights 白夜, The Earthen Gate, and Old Gao Village 高老庄—were Jia’s best, so it’s nice to see that two have finally made it into English. The University of Oklahoma Press put out Howard Goldblatt’s translation of Ruined City in 2016, and Valley Press commissioned Hu Zongfeng 胡宗锋 of Northwest University 西北大学 to translate The Earthen Gate.

More…

By Dylan Levi King, May 3, '19

I've got a Twitter timeline full of 5G hysteria, Huawei backdoors, GitHub protests against the tech sector practice of 996 working hours (9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days a week), the UAE running a drone war in Libya with Chinese tech, a Chinese developer getting nabbed for leaking a wildcard SSL key, Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States pressuring the Kunlun Group to sell Grindr, etc. etc. etc.—the world runs on but seems deeply anxious about Chinese tech.

That makes Pang Bei's Unicorn, a cautionary fable set in the present day Shenzhen tech world, very timely.

More…

By Dylan Levi King, April 19, '19

This is the record of a few days spent with Jia Pingwa and Nicky Harman in Xi'an and environs, as we prepare a translation of Jia's Qinqiang for AmazonCrossing.

I’d already spent the last several days with Jia Pingwa, hanging out in Xi’an and going down to the countryside, but, sitting at a table with the author one night at in Sichuan restaurant off the Second Ring Road in Xi’an, I was dying to do what I’m sure many people have already done: tell him how I first came to read Ruined City.

I think I wanted his approval, to prove to him that I was connected to his works or that I could understand it and that I was the right person to translate it, even if that decision was no longer in his hands.

More…

By Dylan Levi King, October 27, '10

Western critics have expected Chinese authors to unambiguously answer political questions, to stake out their positions, to be in opposition to Mainland China's prevailing social order. Chinese books are mostly translated into English and published by university and academic presses to support Western ideological claims, and everybody stopped reading them a long time ago.

So, if I had to jot a list of reasons that Jia Pingwa has never really been translated into English in a major way... somewhere on that list, I'd note a cultural conservatism that doesn't appeal to Western readers of Chinese fiction, and I'd also list a general ideological subtlety. When Jia Pingwa's Turbulence dropped, it was met with kindhearted confusion, and reviews of it still resorted to calling it a critique of "the bureaucracy that hamstrings modern China." They had nothing else to say. Okay. What if Jia wrote a novel set during the Cultural Revolution?

Just like you've always wanted to hear Rod Stewart rip into "My Funny Valentine," there are those that are stoked to have, say, Mo Yan tear into the central government's family planning policy or have Jia Pingwa really get into the Cultural Revolution.

Jia's early writing, which is not very highly regarded (even by Sun Jianxi, really), is often set casually during the Cultural Revolution ("casually" because it's not the Cultural Revolution of Scar Literature or Western imagination). He has never really laid into the subject, as, I guess, he's been expected to. But... he has now.

More…

By Dylan Levi King, October 10, '10

Internet writing comes in for its fair share of abuse-- check Jia Pingwa in a recent China Daily profile, joking that he doesn't have to stoop to writing about tomb raiders or eulogizing entrepreneurs... or Tibetan mastiffs, I guess... or alienated, aging 80hou kids....

Damn, people are reading it, though.

Even before Yuan Lei (also known as Yuan Ping) got picked up by the Dongguan PD "on suspicion of disseminating pornography," his novel, In Dongguan, posted on Tianya had two million views.

Is there anything beyond the easy story, about (very poorly executed) censorship, which has been picked up by the usual gang of Western China watchers? Anything?

Yes.

More…

By Dylan Levi King, March 27, '10

That's the question in a piece by Wang Yan, for the Liaoning Daily. The article is from a seven part series called, "Re-evaluating Chinese literature."

It features the thoughts of a gang of Chinese scholars, whose opinions range from reasonable to... let's say, unreasonable:

In this installment, "re-evaluating" will take on a slightly different meaning, as we evaluate the position of Chinese literature in a more global sense. We will re-evaluate the status of Chinese literature, from the point of view of cultural exchange and translation of Chinese books. No matter what is achieved in our contemporary literature, the question remains of its standing on the world stage.

Translating books and promoting them overseas is our literary bridge to the West. Currently, that bridge might be said to resemble a plank of wood spanning a wide river. This single narrow and flimsy link to the West is no longer sufficient.

Western translators and scholars of Chinese culture are known as Sinologists. They have been studying China for centuries, but there are very few scholars focusing on contemporary literature. Chinese scholarship on Western literature has a history of at least a hundred years, but Western scholarship on Chinese literature is a field with history of only two or three decades. The West and China do not have an equal understanding of each other. Many Chinese authors are simply ignored by Western scholars. There is a general ignorance of Chinese literature in the West, yet Chinese writers still take to heart everytime China is overlooked for the Nobel Prize for Literature. The West ignores Chinese literature but we still hang on every word that Wolfgang Kubin says. Every Chinese writer still wants to become an international writer. Taking all of that into account, let's rethink our answer to the question of how far Chinese literature has progressed down the road to global acceptance.

More…

By Dylan Levi King, February 20, '10

Jia Pingwa's novel Qin Qiang (The Writers Publishing House, 2005) won last year's Mao Dun Literary Prize and is another masterpiece by the prolific author, whose works are still mostly unknown and untranslated. What is there to appeal to translators and potential readers in the book? When are we going to see it in translation?

From the first half of the book, romance, rats and local politics in rural Shaanxi:

I still remember the rat that crawled out of the sewer. I raised him as a pet. He'd climb on the ceiling rafters and dance for me. After he was tired of dancing, he'd look down at me. His eyes were all pupil, dark black pupils that glinted with mischief. Cats knew not to venture close to my home. After my father died and I was left alone, nobody knew how I spent my time. But the rat knew. Each morning, I'd wake up and place three sticks of incense in front of the portrait of my deceased father, then sit down to write in my diary. In Qingfeng Jie, I was probably the only one who was writing away at a diary. From the incense burner, a ribbon of dark smoke slowly curled upward. It lengthened, reaching up to the rafters, where the rat watched me write. The rat thought it was a string and he leapt out, hoping to slide down it, to the table. Pow, he crashed down into the incense burner.

I've heard people say that rats are smart but they can be pretty dumb, too. This rat was rather fond of me, actually. But one of the reasons he stuck around for so long was because my house always had something to eat. I heard that last year when Mao Dan from Dong Jie got sick, he had to sell everything to pay the doctor bills. Every rodent that had previously made a home in his house escaped as soon as the food was gone. What I wanted to say is: this rat was civilized. He even chewed up the pages in my diary, the ones about Bai Xue. I looked at him in wonder, You know that I miss Bai Xue? Rat, if you can understand me, run to Bai Xue and tell her how I feel. He immediately took off to Xia Tianzhi's home and Bai Xue's bedroom. The rat climbed up and down the mosquito netting that was wrapped around her bed. Bai Xue looked up, "A little thief, eh?" She used an empty makeup box to trap the rat inside. The box still had a bit of foundation powder inside. With the powder spread over his fur, the rat pitifully squeaked, "Yin Sheng misses you! Yin Sheng misses you!" Bai Xue didn't understand what my rat trying to tell her.

After a while, the rat wandered into the main room of the house, where he found something else to chew on: one of Xia Tianzhi's scrolls of calligraphy. The one that my rat chose to chew had been scrawled by the director of the county's cultural research insitute. When Xia Tianzhi discovered the holes in the scroll, he shut up the windows and the doors and trapped my rat inside the room. He tossed the rat to the mute to look after. The mute carried the rat outside, doused the tiny body with kerosene, set it on fire and tossed it to run in the big courtyard in front of the theatre. The rat immediately burrowed into a heap of wheat straw. The straw immediately caught on fire.

More…