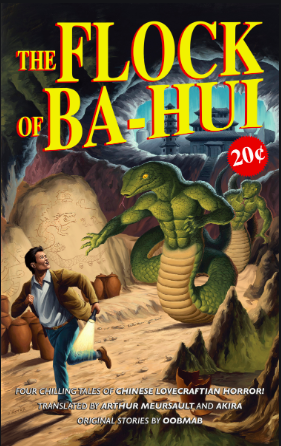

The Flock of Ba-Hui and Other Stories from Camphor Press, a collection of Lovecraftian horror by a pseudonymous author is among the more interesting works to appear recently in translation from Chinese.

Of course, web novels and online writing have made it into translation before. I’m thinking of Shen Haobo 沈浩波, who made a name from poems published online (and who once made a living as a publisher of online lit), and also Murong Xuecun 慕容雪村, whose Leave Me Alone was first posted online—some of that has made it to ink and paper, but most of the translation of web stuff remains online, and it’s mostly in the form of light novels, like Godly Stay-Home Dad 神级奶爸 and the nearly 5000 chapter Martial God Asura 修罗武神 (it could be 10,000 chapters by now).

I’ve pulled examples from two extremes—work mostly of interest to academics on one side, wildly popular wuxia fantasies on the other—but the stories in The Flock of Ba-Hui probably sit somewhere in the middle: still genre fiction but from a slightly more serious tradition, and written with more attention to the craft. They were culled from the Ring of Wonder, a discussion board for fantasy worlds, games, and literature.

Although Lovecraft left a fairly slim oeuvre behind when he died in 1937, his work has inspired countless writers and artists to pick up where he left off, writing in the same extended Lovecraftian universe, or the "Cthulhu Mythos." The author of the stories in this collection—the pseudonymous Oobmab—is treading a similar path. As Arthur Meursault reminds us in the foreword to his co-translation, Lovecraft was the “first open-source programmer."

In the West, Lovecraft has experienced something of a revival in recent years, but I think it’s fair to say that his influence never really waned in East Asia, where Lovecraftian esthetics have infected manga, light novels, and anime. As Houellebecq says of Lovecraft fans in the West, many haven’t read the author’s own work: “They haven’t read him, and haven’t any intention to do so. However, curiously, they long—regardless of the texts—to know more about this individual, and the way in which he constructed his world.”

Until recently, Lovecraft fans in China would have to read most of his work in English. There’s record of a translation of Lovecraft’s "The Music of Erich Zann" appearing in the KMT-established Literary and Art Vanguard in 1948, but not much between then and the early 2000s. In the past few years, the number of Lovecraft releases has ramped up: there was a translation of The Call of Cthulhu and Other Weird Stories by Li Heqing 李和庆 and Wu Lianchun 吴连春 from an imprint of People's Literature 人民文学出版社 in 2016, and when I was at the Beijing International Book Fair last year, I saw that the third volume of a Cthulhu Mythos 克苏鲁神话 collection, translated by translated by Yao Xianghui 姚向辉, had been published by Zhejiang Literature and Art Publishing House 浙江文艺出版社.

The collection’s titular story, “The Flock of Ba-Hui,” is related by the colleague of a young archeologist, Zhang Cunmeng, who has gone missing and is presumed dead. Zhang is the perfect Lovecraftian hero, a complete cipher, dedicated only to an intellectual pursuit—in this case, proving the existence of an ancient state called Nanyu, based on his own archeological findings. Using hints from a scroll he has found, he goes looking for traces of the extinct kingdom, which seems to have worshipped a serpent god, called Ba-Hui.

Zhang returns from a long absence with a few pottery shards, but he ends up being committed to a mental institution after torching his notes and burning down the house. Shortly after being confined to the institution, Zhang goes missing, but our narrator recovers one of his scorched notebooks. He gets together some colleagues and they set off to retrace the steps of Zhang Cunmeng, finally locating the cave where he collected the pottery shards. They enter the cave to find that its walls are painted with frescoes describing fantastic beasts, war, and cannibalism

The stories only get better from there.

If you have a thing for weird fiction, it hits all the right notes.

The work of the two translators here is very impressive. This is not easy material, and it requires a deep knowledge of Lovecraft and his oeuvre. Arthur Meursault, the pseudonymous co-translator, is the author of Party Members, and his style perfectly suits the Lovecraftian purple prose.

This was more fun to read than anything else published this year in translation.

Comments

Hooray!

Dylan is back as we navigate the hideous Era of the Wuhan -- oops -- COVID-19 Pandemic that wasn't.

Lovecraftian. Sounds just right. By the way, what's the Chinese for this delightful term?

Bruce Humes, March 11, 2020, 3:41a.m.

Maybe we'll go with 洛夫克拉夫特风格的? Doesn't roll off the tongue quite the same, though.

Dylan Levi King, March 11, 2020, 3:16p.m.

No doubt has a better ring in katagana-powered Japanese!

Bruce Humes, March 12, 2020, 1:41a.m.

I'd called tRump-Pandemic ...suggested by many twitters in this side of Pacific realm..

sye, March 18, 2020, 6:11p.m.