Posts

By Bruce Humes, December 9, '19

First, it was Howard Goldblatt and his renditions of Mo Yan's novels that helped the Shandong storyteller win the (once coveted) Nobel Prize in Literature. Goldblatt has made it no secret that he edited the text in order to heighten readability.

Now, via an interview with Ken Liu in the New York Times, Why Is Chinese Sci-Fi Everywhere Now? Ken Liu Knows, we learn that translator Liu played a similar role in making Liu Cixin's The Three-body Problem popular in the West:

More…

By Bruce Humes, November 17, '19

The Spanish-language database here is searchable in several ways:

Title in Spanish

Original title in Chinese

Author

Translator

Genre

Entries for each of the above are also listed alphabetically, so you can scroll for a look at what is in the database even if you don't have a particular book/author/translator in mind.

It is not anywhere as complete as MCLC's one in English, but still useful.

By Bruce Humes, October 9, '19

The new emperor’s Belt & Road Initiative has already resulted in scores of contracts for highways, railways and port construction in Central Asia, Southeast Asia and even East Africa. Perhaps less well known is the PRC's solidly financed soft power campaign that aims to create or translate, publish and disseminate texts in the languages of the “Silk Road” peoples — land- and sea-based — that relate to the history of the ancient trade routes.

This post features the tale of Zhang Qian, diplomat and explorer of the “Western Realm” during the reign of Emperor Wu of Han (141-87 BCE). The book is in Chinese and Mongolian (traditional script) and forms part of a "Socialist Core Value" (社会主义核心价值观幼儿绘本) picture-book series for children aged 5-6.

To facilitate comparison, the blogger has provided the text in three languages, five scripts: the original Chinese and Inner Mongolian script (vertical); Hanyu Pinyin; Cyrillic Mongolian (used in Mongolia); and a translation of the text into English.

More…

By Bruce Humes, September 27, '19

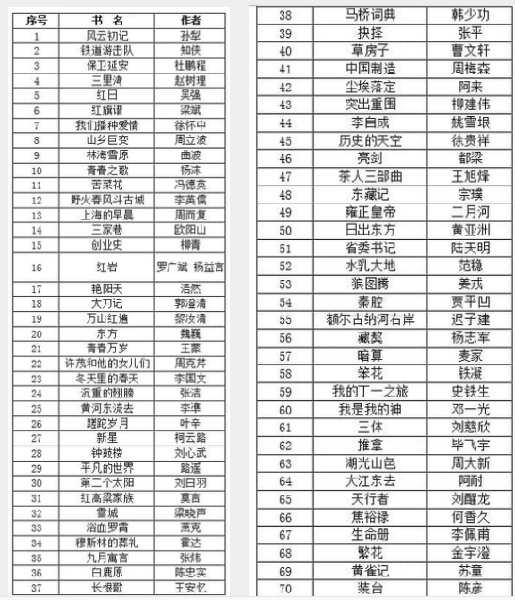

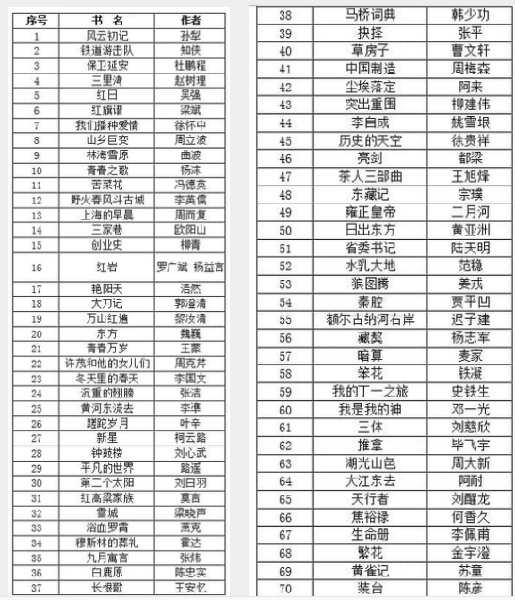

Fittingly, to celebrate the upcoming 70th anniversary of the birth of the PRC, a list of 70 post-1949 novels—“must-stock” classics for libraries nationwide, apparently — has been drawn up by the People’s Literature Publishing House and Xuexi Publishing House. See here for the Xinhua press release and full list.

Given that about one out of ten PRC citizens is identified on his or her ID card as a member of an ethnic minority, it might be interesting to scan the list for novels that classify as "ethnic fiction," i.e., a loose category (民族题材文学) that includes stories — regardless of the author’s ethnicity — in which non-Han culture, motifs or characters play an important role.

More…

By Bruce Humes, January 21, '19

China-based publishers are notorious for a misleading practice: the nationality of the author — not necessarily the language of the source text — is often noted on the spine or copyright page. Thus the reader may well believe she is reading a novel translated direct from the Swahili, when the source text is actually the English rendition of a Swahili original...

If you're interested in reading and/or adding to several comments on this topic, please click:

http://bruce-humes.com/archives/12862

And see the comments immediately below the article itself.

By Bruce Humes, January 1, '19

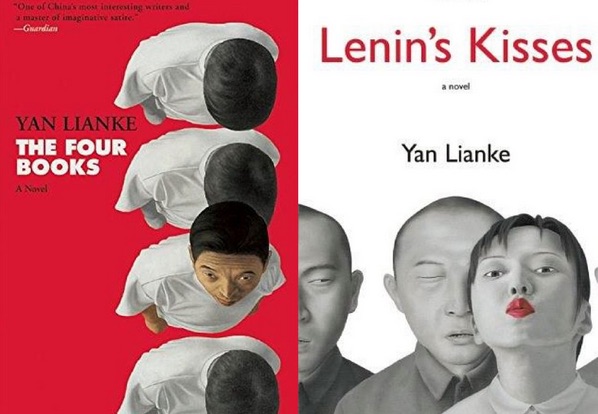

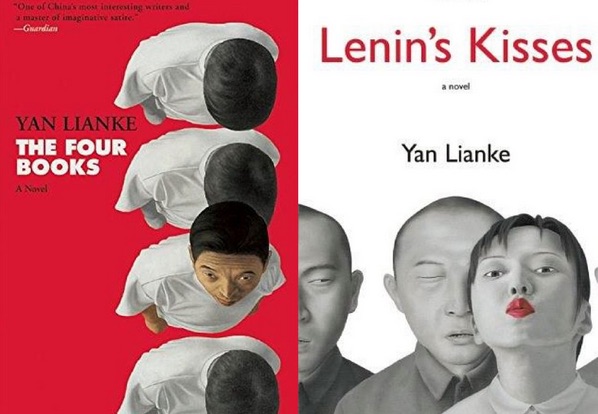

Several of Yan Lianke's novels have not been published in China, or were initially published in Taiwan because he couldn't find a publisher in the PRC. Although he teaches at Renmin University of China in Beijing, the authorities seem keen to silence much of what he says, in fiction or otherwise.

Such is the case with a Dec 27, 2018 interview of him by The Beijing News (新京报), which has already been taken off the internet (looks like I'm wrong, see comments!), but saved -- for now anyway -- in a Google cache file.

Entitled 一个伟大文学的时代已经悄然消失, it can be found here in text form, and here with several photos (covers of his novels + a few of him).

I have copied the entire interview below in Chinese (text only).

More…

By Bruce Humes, October 2, '18

The Guardian reports that former secretary of state and Massachusetts senator John Kerry made the following comment on the current rush to vote on the nomination of Brett Kavanaugh to the US Supreme Court:

“There’s no reason in the world to be bum-rushing this nomination.”

How to render "bum-rushing" as used here?

By Bruce Humes, March 26, '18

Speaking at length during his recent coronation ceremony, the new emperor mispronounced the name of the Tibetan epic, King Gesar, as "King Sager" (习近平把 “格萨尔王” 说成 ”萨格尔王”).

Unsurprisingly, this news did not appear under the headline "President Hurts the Feelings of Millions of Tibetans" in The People's Daily next day.

It is significant that he mentioned two of the three ancient oral epics in his speech, King Gesar (Tibetan) and Manas (Kyrgyz). Chinese literary apparatchiks increasingly refer to them, including Jangar (Mongolian), as “China's Three Great Epics” (我国三大史诗). This despite the fact that they originated in languages other than Chinese, among non-Han peoples and in lands that were not then part of the Chinese empire.

Alerted about it via a tweet by Shawn Zhang (章闻韶), however, Victor Mair's Language Log did discuss XJP's verbal faux pas that went unreported in China mainstream media.

More…

By Bruce Humes, August 27, '17

Glossing Africa is a fascinating piece on “glossing” — different ways to do it, and what it signifies when it is (or is not) employed. In this piece, glossing refers to practices for clarifying an indigenous term by providing a glossary, footnotes, inserting a brief definition, etc.

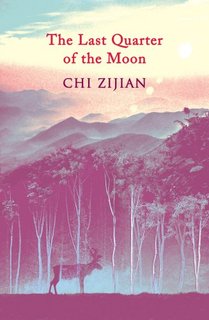

Of course, we translators also frequently have to decide whether to gloss or not. In Chi Zijian’s Last Quarter of the Moon, for instance, I counted about 125 Evenki terms, including for proper names, place names and unique aspects of Evenki culture. More recently, Liu Jun and I co-translated Confessions of a Jade Lord by Alat Asem, in which there are many Uyghur and Arabic terms.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, the popular Nigerian author now splitting her time between the US and Nigeria (and one of the rare contemporary African authors to have several novels available in Chinese), is definitely not a fan of glossing:

There’s a part of me that just deeply resents the fact that there’re many parts of the world where the fiction that comes from there is read as anthropology rather than as literature. And increasingly that kind of anthropological reading then means that… you’re explaining your world rather than inhabiting your world.

By Bruce Humes, August 14, '17

Each year there are dozens of literary events timed to coincide with the Beijing International Book Fair (Aug 23-27, 2017). They take place both on the fair grounds and throughout the capital, and sponsors include Paper Republic.

As lists of these events-- in Chinese or English -- become available, please list here so that we can all benefit . . .

By Bruce Humes, July 20, '17

Sad to learn that the last Jifeng Bookstore (季风), located at the Shanghai Library metro station, will close its doors in January 2018, according to the South China Morning Post. The original opened at Shanghai’s South Shaanxi Road metro station in 1997, and a string of other branches followed over the next decade.

It was during a break from my busy China speaking tour in 2000 about how importers abroad were using the Internet to source China-made goods, that right there in the South Shaanxi station I happened upon a copy of the very naughty 上海宝贝, the first Chinese novel I was to translate (Shanghai Baby). If it hadn’t been banned by then, it was certainly banned quickly thereafter.

The SCMP makes it clear that Jifeng is closing because the Shanghai authorities continually interfere with its efforts to host seminars and the like, events often referred to as 文化沙龙. This puts the few remaining independent booksellers in a bind: Book sales are increasingly monopolized by online vendors and massive Xinhua Bookstores, yet when independents try to branch out into other types of products and services — à la Eslite in Taiwan (诚品书店) — they are thwarted by the local culture department.

By Bruce Humes, May 30, '17

It can take several years for a piece of Chinese fiction to reach the English-speaking world. But thanks to publication in Chinese on the Internet — and translators working from it rather than the printed book — it looks like this time-to-foreign-reader can be radically reduced. Hopefully, this will help outsiders more quickly grasp what is going on in the “black box” that is China.

Reports Manya Koetse: “I Am Fan Yusu” went viral on Chinese social media in late April 2017. The author has since gone into hiding and her essay has been removed.

In some ways, the popularity of the essay in China is comparable to the recent hype over Alex Tizon’s essay “My Family’s Slave” on Western social media; this non-fiction story about ‘Lola’ Eudocia Tomas Pulido from the Philippines, who lived as a modern slave with an American family for 56 years, went viral on Twitter and Facebook in May. It gripped its many readers for exposing poignant problems in modern-day society that usually stay behind closed doors.

Fan Yusu’s account, in its own way, also revealed the harsh realities of an ever-changing society. China has an estimated 282 million rural migrant workers. The autobiographical tale focuses on the difficult childhood and adult life of one person . . .

More…

By Bruce Humes, May 20, '17

Buruma knows Chinese and often writes about topics related to China and Japan. See news of the announcement here.

By Bruce Humes, May 19, '17

France’s Macron has named a woman, Françoise Nyssen, to fill the position of Minister of Culture. She has served as CEO of Éditions Actes Sud, which has published French translations of works by writers such as Bi Feiyu, Chi Li, Ma Jian, Mo Yan, Li Ang, Wang Xiaobo, Wuhe, Yu Hua, Zhang Xinxin and Zhaxi Dawa.

By Bruce Humes, January 23, '17

The Donald and his critics have media worldwide talking about two terms:

Fake news

Alternative facts

How would you render them?