Our News, Your News

By David Haysom, February 3, '17

What is this thing you call “Chinese Literature”?

“Chinese literature” is often a conveniently nebulous term that means different things to different people. It can refer to China as a geographical or political entity – except not everyone agrees on what that is. Or it can be a linguistic description, referring to what is sometimes called the “Sinosphere” – except there’s no undisputed definition of what exactly constitutes a language. Depending on where you draw your line, “Chinese literature” may or may not encompass: mainland China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macau, Singapore, Malaysia, diaspora authors writing in Chinese, diaspora authors writing in English, and ethnic minority authors writing in completely different languages (such as Tibetan, Mongolian, or Manchu). Many of them would reject the label of “Chinese literature”, and its capacity to cause offence (and incite semantic spats) is far greater than its descriptive utility. And yet, for the sake of convenience, we do need to have some kind of term to refer to this thing we are all interested in, and “Chinese literature” is the best we currently have.

More…

Epiphany Magazine is now accepting submissions for its spring translation contest, deadline February 20. Submissions will be judged by Ann Goldstein, and the winner will receive $400. See link for details.

By David Haysom, February 2, '17

“I like the idea that you could have actual readable pieces hanging off the database, like ornaments on a Christmas tree. So as you go browsing, you also find things to read.”

“This is something I’m really keen on!”

“A catchy title would help, e.g. #TranslationThursday Weekly Story. (Sorry, that's not very catchy.)”

“We don't necessarily need a catchy name of our own – I think just calling it something like "Paper Republic's Translation of the Week" would work fine.”

“I've been using ‘read’ as a name for things in the backend of the site, and wonder if ‘Read Paper Republic’ might be an okay series title.”

“I like it!”

More…

By Eric Abrahamsen, February 1, '17

Zhang Lijia, author of Socialism is Great!, is talking about her first novel, Lotus, February 1 7pm at the NY Barnes & Noble, 82nd and Broadway. See this link for more information, and stop by if you're in town!

From the event blurb: Inspired by the secret life of author Lijia Zhang's grandmother, Lotus follows a young woman torn between past traditions and modern desires as she carves out a life for herself in China's "City of Sins." This perceptive, sensitive novel examines what it means to be an individual in a society that praises restraint in and obedience from its women.

By Eric Abrahamsen, February 1, '17

The wonderful people over at the Global Literature in Libraries Initiative have designated February as China month, and have asked us to help! So for a whole month, we'll be posting on the GLLI site and on Paper Republic. First post - for the GLLI readers - what is Paper Republic? Who are we and what do we do?

More…

By Helen Wang, January 28, '17

Happy New Year everyone! Wondering what's in store on Paper Republic in the Year of the Rooster?

READ PAPER REPUBLIC's first project of the year starts on Wednesday 1 February and runs throughout the month. The Global Literature in Libraries Initiative (GLLI) invited us to run their blog, and give it a China focus for February. We said yes, as long as we could post the blogs simultaneously on Paper Republic. So that's what we're doing! We'll be posting every day through February. We're incredibly grateful that so many PR contributors and friends have helped us to prepare for this, and we hope you'll enjoy the posts. As usual, please join in and leave comments (especially appreciative ones! and ones that add news or info).

-- The Read Paper Republic Team

By Nicky Harman, January 26, '17

The 2016 Marsh Award for Children's Literature in Translation was presented last night to our very own Helen Wang for her translation of Cao Wenxuan's Bronze and Sunflower. Celebrations and congratulations! More news and reviews to follow.

By Bruce Humes, January 23, '17

The Donald and his critics have media worldwide talking about two terms:

Fake news

Alternative facts

How would you render them?

Creative nonfiction is thriving in the People’s Republic. To journalists, it provides creative and financial space that is hard to find elsewhere in media. To the real-life protagonists, it provides new opportunities to make their stories heard. (Tabitha Speelman, in supchina)

The unique feature of Chinese online literature is that most works are serialized novels that authors write and post in installments (a new form of “content”). Every day, millions of young digital-reading users refresh their mobile apps, just to keep up with the latest daily updates of their favorite reads. For many people who do not have the time to read a book in hard copy, the novels on a mobile phone (a new “connection”) can be easily read whenever they have some spare time.

The installment format also helps the literature websites to implement a pay-for-content mechanism. When authors start to build up large readerships, the online portals offer them contracts and move their works off the free domain. The sites arrange for the authors to write stories in instalments (typically with a total character cap for each post), and readers then pay a tiny fee equivalent to a fraction of US$ 0.01 to read each update, far cheaper than paying for hard copy versions from a book store.

(Review by James Kidd) By following a village in central China as it becomes a city, Yan has found a way to illustrate the country’s incredible transformation, narrated in transparent prose full of lyrical symbolism

Interesting interview with Ken Liu.

Liu: I think that what's unique about sci-fi--at least from the view of a lot of Chinese writers--is that sci-fi is least-rooted in the particular culture that they're writing from.

There's a phrase among Chinese writers that says, "there are no glazed tiles on Mars." What it means is this: Chinese palaces, traditionally, are covered with glazed tiles, or glazed shingles if you will. The point of the phrase is, when you go into space, you become part of this overall collective called "humanity." You're no longer Chinese, American, Russian, or whatever. Your culture is left behind. You're now just "humanity" with a capital H, in space.

Two-day bilingual (Chinese and English) training to be held on Feb 6-7 in Taipei as part of the 2017 Taiwan Int'l Book Exhibition. Includes sessions on editing a book-length translation, editor-as-publisher, case studies on legal issues, on-hands editing workshop and more.

National Book Development Council of Singapore deputy director Kenneth Quek says populist movements, such as We Need Diverse Books, have raised demand in Western markets for stories not set in the US or Europe.

He adds: "The US and British markets, while still quite large, have stagnated. Asia holds a large, somewhat untapped market and Western publishers are beginning to cater to it."

At 68 characters long, the new title is the longest yet for a light novel -- and causing problems both at home and overseas. It's been pointed out that the longer the title is, the more difficult the book becomes to catalog in a database, where space is at a premium. With a 68-character-long title, there may end up not even being room for a description of the book... which is a big problem if it's a new release that needs extra information added to its entry.

As a young man Mr Zhou spent time in the US and worked as a Wall Street banker.

He returned to China after the communist victory in 1949 and was put in charge of creating a new writing system using the Roman alphabet.

"We spent three years developing Pinyin. People made fun of us, joking that it had taken us a long time to deal with just 26 letters," he told the BBC in 2012.

PRH has signed a conditional agreement to sell Penguin Singapore and Penguin Malaysia to Times Publishing, an Asia-Pacific media group owned by parent company Fraser and Neave.

The original headline, in China Daily, is "Chinese novels make waves globally".

On 16th December for the Found in Translation event, as part of the China Changing Festival, at Southbank Centre, she was one of three on a panel discussing contemporary Chinese fiction, with Hong Ying, and Guo Xiaolu. We invited her prior to the discussion to talk more about writing, her cultural encounters, and the challenges of translation.

China Info 24 met famous Chinese author Yan Geling at Southbank Centre’s China Changing Festival last Friday [16 Dec]. In an exclusive interview, she shared her inspiration for writing her latest English novel, Little Aunt Crane, what it means to be labelled as 'a female writer', and how living outside of China has given her a distinctive perspective in understanding the country's history.

"Unlike the export of individual printed literary works, the spread of [China's] online literature oversees can be seen as the dissemination of an entire cultural system."

On the surface, the protagonist of Ge Fei’s novel is a recognizably down-trodden everyman, a soft-spoken narrator who describes himself to us—in the intimate first person of the narrative—as one of the handful of people in Beijing still capable of building a top-end tube amplifier, eking out a living by hand, producing top-quality, artisanal sound systems. Since the boom years in the 1990’s, when (Western) classical music was still revered and a skilled audio technicians were in hot demand, Cui has seen his craft dwindle and fade. His continued devotion to his craft, then, what he calls “the most insignificant industry in China today,” allows him to tell a simple story about the decline of labor: in a booming economy where “today’s craftsmen more or less exist on the same rung of the social ladder as beggars,” he describes his aesthetic labor as a figure for what has been left behind in the great economic leap forward. Most of his clients are clueless billionaires, aching for extravagance to spend their money on; the rest are self-important intellectuals, drowning in their own pomposity. No one appreciates the delicate art of his craft, or its product; his speakers are pearls bought by swine.

(1) Junkyard Poetics: Ouyang Jianghe’s Phoenix

(2) Of Gods and… More Gods: Idle Talk Under the Bean Arbor

(3) A Man and His Rock

(4) Moonstruck: Wandering the Galaxy with Li Bai

(5) Grief in a Fallen City: Du Fu’s Ever-Present Histories

(6) High Plains Drifter: Li Shangyin

(7) Revolution or Reform: A Discussion of the May 4th Movement

(8) A Male Mencius’ Mother

(9) ‘Cause I’m the Taxman: The Voyages of Yu Gong

(10) Emperor Shen’s New Groove: Song Dynasty Exam Reform

My own concern is that it’s getting harder and harder to get people excited about Chinese books, movies or comics unless they are ‘banned in China.’ This lack of interest in apolitical narratives, or one which fall outside the narrowly defined concept of dissident literature means that people aren’t really engaging with China in a way that allows them to understand what is actually happening in the country today. [...] A total disconnect between China and the rest of the world makes solving tough issues like global warming and rising income inequality that much harder, because we have so few common points of reference.

This is a big difference between, say, translating from Chinese into English as opposed to other Western languages that have similar kind of Greek and Roman, Latin roots. And so because of that if you’re translating, say, into French, or Italian, into German, there are a lot of words that come from the same roots and so it’s kind of a no brainer what your word choice is going to be because there is a very clear equivalent in—not all, but in many cases. In Chinese, it’s not nearly as clean-cut like that. So if you take—I’ll just throw out a term in Chinese like “bēishāng”, which usually is translated something like “sadness” but it could also be translated as “melancholy” or “depression” or any number of other similar terms. And so it’s all about really getting the context right and the register of the language and finding in this context what English term is really best going to express what “bēishāng” was representing in that original Chinese work. And so that means for the translator that we have a lot more leeway to be a little more creative, to have a little more kind of an interpretative intervention into the nuance of the original. It also means there’s more room for mistakes. That if you don’t have a great grasp of the original language you could go the wrong direction and miss that nuance. And so I think it is somewhat different in that sense then when you’re translating from other Western languages.

“We can safely say that all themes once explored in the American and European sci-fi genre have found their manifestation in the Chinese counterpart – things like space exploration, alien contact, artificial intelligence, and life science. Problems of modern development are also addressed, like environmental hazards and the negative effects coming from new technologies. Yet Chinese sci-fi does have its own unique themes as well, such as the attempt to re-deduce and re-display the ancient history of China from a sci-fi angle.”

We’re all familiar with unreliable narrators, those first-person storytellers whose words we are not sure we can trust. In The Invisibility Cloak, Ge Fei takes this to the next level: he gives us an unreliable narrator in an unreliable career struggling with unreliable characters in an unreliable country.

What is reliable in The Invisibility Cloak is the translation. This is Canaan Morse’s first full-length novel, but he is one of a new generation of ambitious translators who are redefining standards of quality in writing English without sacrificing accuracy in treating the Chinese. Lexical range tends to flatten in translation, but checking his English against what Ge Fei wrote I am again and again impressed with Morse’s vocabulary, and his ability to find lively, expressive language that never comes off as stilted or stiff. This is essential for any work in translation, of course, but when the work revolves, as it does here, around questions both of reliability and communicability, it is an added bonus that readers do not need to worry about whether The Invisibility Cloak’s inner life has been left alone in another language.

The number of detained and imprisoned writers in China is among the highest in the world. In an open letter released by freedom of speech group PEN International, and published in the Guardian on World Human Rights Day, the signatories condemn the constriction of freedom of expression by Chinese authorities and say they “cannot stand by as more and more of our friends and colleagues are silenced”.

Dave Haysom ... said it is crucial to understand target readers. ... “These kinds of grants can certainly be helpful, and the money needs to be used in the right way if it’s going to really have a positive impact,” Haysom explained. “One of the most productive ways to achieve that is to forge closer links with foreign publishing houses and gain a better understanding of how they operate.”

The advantages of Chinese characters in avoiding grammatical specificity (advantages to poets, not necessarily to scientists or lawyers) can be analyzed primarily as absences of subject, number, and tense. Each of these three is worth a look . . . subjectlessness, numberlessness, tenselessness.

The Literary Tourist is a column of conversations between literary translators about newly released books in translation. This month Andrea Gregovich interviews poet, editor, and Chinese translator Canaan Morse. Canaan co-founded the literary journal Pathlight: New Chinese Writing as its first poetry editor, won the Susan Sontag Prize for Translation in 2014, and has published translations and book reviews in several international journals, both print and online. The Invisibility Cloak, a captivating experimental novel by Ge Fei, is Canaan’s first translated book.

By Nicky Harman, December 4, '16

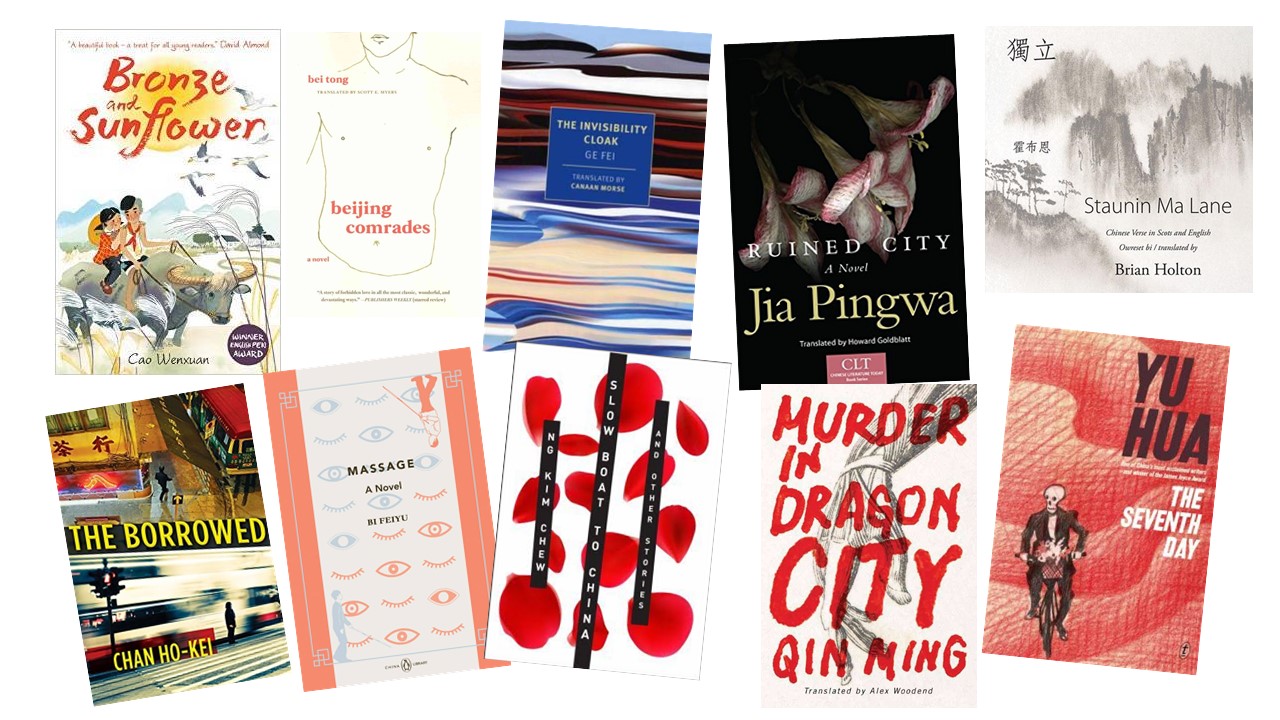

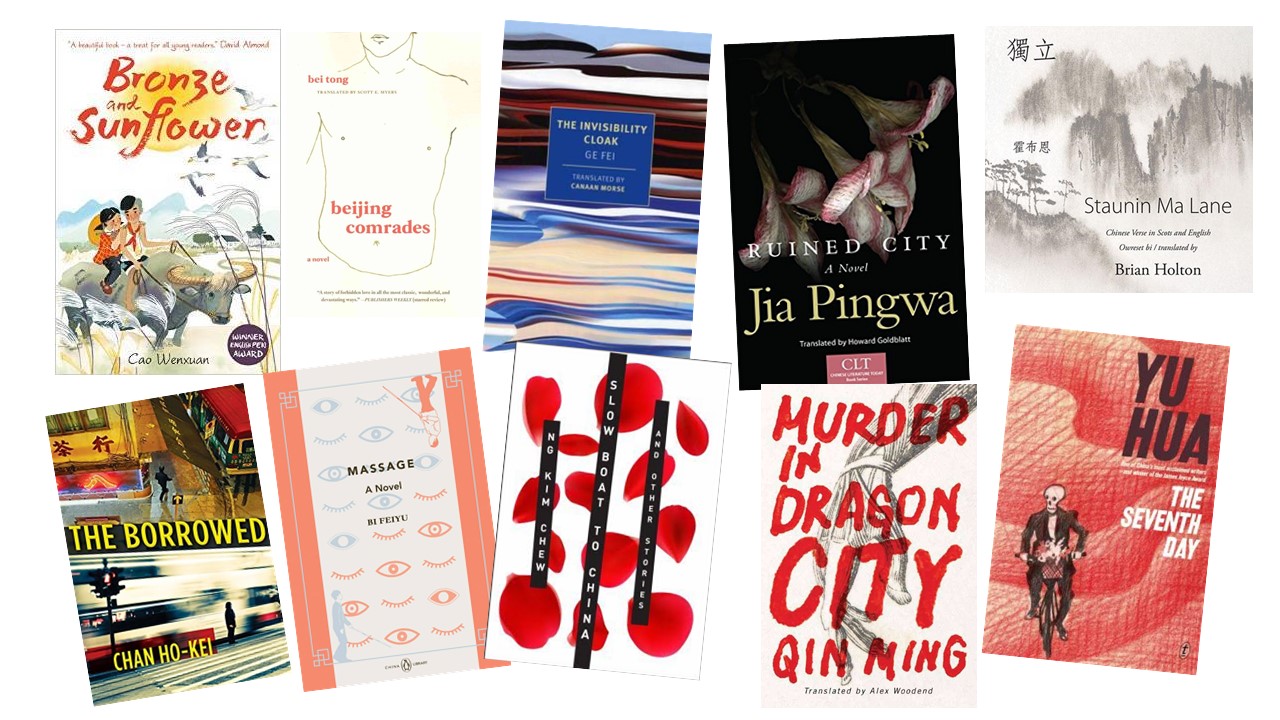

As usual, we have assembled a list of book-length translations from Chinese into English over the year. Congratulations to all authors and translators! This year’s list is longer than ever, and several books have won international prizes. Your additions, comments, corrections to this list are welcome - please leave a comment below and we’ll update the list. This is our fifth annual list; previous lists are here: 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015...........

More…

By Nicky Harman, December 3, '16

In 2015 and 2016, Paper Republic were honourable runners-up. Asymptote won in 2015, Words without Borders in 2016. Anyone can nominate any group/collective/organization...so to put in your nominations, see below.

The London Book Fair and UK Publishers Association are seeking entries from non-UK organisations for The Literary Translation Initiative Award at the LBF International Excellence Awards. Closing date is 15 December 2016.

Organisations that have succeeded in raising the profile of literature in translation, promoting literary translators, and encouraging new translators and translated works should apply/be nominated.

Who is eligible? Any company or organisation operating outside the UK, whose scope of achievement is outside the UK.

This is a great opportunity to follow in some illustrious footsteps, to be recognised by your peers and get some good publicity for your company. The shortlist for the awards will be unveiled in February and the winner announced at a gala awards event on Tuesday 14 March, during LBF.

To enter or learn more about the awards go to www.londonbookfair.co.uk/awards

Cold has pierced our hearts

We have made nature sympathize with us

We even spell out pity in trampled petals

The next step is keeping each other warm

By Helen Wang, November 30, '16

The Chinese name of the grant (《上海翻译出版促进计划》 翻译资助) translates more literally as the "Shanghai Translation Publishing Promotion Scheme translation grant". The terms and conditions can be found here. Details of the winners of 2016 Shanghai Translation Grant can be found here.

More…