Cindy M. Carter 辛迪

worldcat |

contact

Cindy M. Carter is a Beijing-based American translator of Chinese fiction and film. Since coming to China in 1996, she has translated over 50 award-winning independent Chinese films and documentaries, dozens of scripts, short stories, essays and poems and 2 novels. She is currently the in-house translator and editor at Ullens Center for Contemporary Art (UCCA) in 798 Art District, Beijing.

Fiction

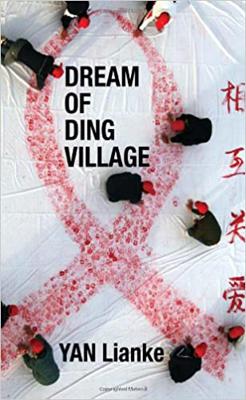

Dream of Ding Village by Yan Lianke. 2011. Constable and Robinson (UK) / Text Publishing (Australia) / Grove Press (US). 352 pages. Prose-poetic tale of blood-selling, AIDS, profiteering and revenge set in rural Henan. (Long-listed for the 2012 Man Asian Literary Prize.)

"But the sickness had only just begun. [...] The real explosion wouldn't come until next year, or the year after next. That's when people would start dying like sparrows, or moths, or ants. Right now they were dying like dogs, and everyone knows that in this world, people care a lot more about dogs than they do about sparrows, moths or ants."

Village of Stone by Guo Xiaolu. 2004. Chatto & Windus, U.K. 181 pages.

Fictional memoir of a young woman coming to terms with repressed memories of her childhood in a Chinese fishing village. (Short-listed for the 2005 Independent Foreign Fiction Prize; Long-listed for the 2005 Dublin IMPAC Prize.)

"The Village of Stone was my entire world, my fortress without windows, a place where they had dug my grave almost as soon as I was born."

"Two people together never add up to anything more than one person added to another. That we continue to add ourselves up in this way is the reason human beings will always be lonely."

Selected Documentaries

Karamay by director Xu Xin. 2009. Mandarin with English subtitles. 371 mins. In 1994, over 450 people - mainly schoolchildren and their teachers - were killed or injured when a fire broke out in a theatre in Karamay city, Xinjiang province (see Wiki entry). The survivors, who had been attending a song-and-dance performance to entertain visiting cadres, reported that students were instructed to remain in their seats so that VIPS and party cadres could exit first. Through rare video footage and first-person interviews with families and survivors, Xu Xin documents how the story was portrayed in the official media, the public anger that erupted after the fire and the community's 15-year quest for justice.

WE: Creatures of Politics, Voices of Conscience by director Huang Wenhai. 2008. Mandarin with English subtitles. 102 mins. In the run-up to the 2008 Beijing Olympics, several generations of activists debate the future of political reform and human rights in China. (Special Jury Prize, Venice Film Festival, 2008; Screened at One World Human Rights Festival, 2009.)

Crime and Punishment by director Zhao Liang. 2007. Mandarin and dialect with English subtitles. 123 mins. Young military police patrolling the border between China and North Korea deal with career frustration and local disputes ranging from petty theft to illegal logging to false dead-body reports. (Best Documentary, Nantes Festival des Trois Continents, 2007; Best Director, One World Int'l Human Rights Film Festival, 2007.)

Fairytale, by producer Ai Weiwei. 2007. English, German, Mandarin and dialect with English subtitles. 9 hours. With 16 directors and a crew of 8 translators, Fairytale offers a behind-the-scenes look at artist Ai Weiwei's ambitious project to bring 1001 Chinese people from various walks of life to the 2007 Kassel Documenta in Germany. Subjects include: a policeman-turned-blogger who was refused a passport for his blog posts critical of Chinese law enforcement, a pair of writers whose passion for poetry and fondness for drink goes hand in hand, and a group of farmers whose trip to Kassel will be the first time they've left their village, much less their country.

Fengming: A Chinese Memoir (alt title: Chronicle of a Chinese Woman) by director Wang Bing. 2007. Mandarin with English subtitles. 184 mins. He Fengming speaks directly to the camera of her experiences as a revolutionary, journalist, accused rightist, prison camp inmate and chronicler of more than a half-century of Chinese history. (Grand Prize, Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival 2007; Young Critics Award, Cinema Digital Seoul, 2007.)

Mona Lisa by director Li Ying. 2005. Mandarin with English subtitles. 110 mins. 20 years after being kidnapped as a child-bride, a young woman named Xiuxiu manages to locate her birth parents and lands her kidnappers - the couple who raised her - in prison. Motivated by a sense of responsibility to her adoptive siblings, Xiuxiu tries to get her adoptive mother released on furlough.

Before the Flood by directors Yan Yu and Li Yifan. 2004. Sichuan dialect with English subtitles. 143 mins. As the flood waters of the Three Gorges Dam Project rise, dislocated residents of the ancient town of Fengjie clash with local cadres and try to find new lodgings. (Grand Prize, Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival, 2005; Best Documentary Feature, Lisbon Int'l Documentary Film Festival, 2005; Winner, International Competition, 2005 Cinéma du Réel Film Festival; Wolfgang Staudte Prize, Berlin Film Festival, 2005; Humanitarian Prize, Hong Kong Film Festival, 2005.)

West of Tracks by director Wang Bing. 2003. Mandarin and Shenyang dialect with English subtitles. 545 mins. Sweeping three-part documentary (I: Rust, II: Remnants, III: Rails) depicts the lives of laid-off factory workers and their children in Shenyang, China's rust belt. (Best Documentary Feature, Mexico City Film Festival, 2005; Grand Prix, Marseille Festival of Documentary Film, 2003; Grand Prize, Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival, 2003; Golden Montgolfier Award, Nantes Festival des Trois Continents, 2003; European DVD release: MK2 films.)

Paper Airplane by director Zhao Liang. 2001. Mandarin with English subtitles. 89 mins. Gritty documentary about heroin addiction and the Beijing underground music scene. A film that made the subject matter less taboo - and inspired numerous feature-film knockoffs - it's still the only one that gets the story right. (Merit Prize, Taiwan International Documentary Festival, 2002.)

Selected Feature Films

Fujian Blue, (See also: Wiki entry) by director Robin Weng (Weng Shouming). 2007. Fujian dialect with English subtitles. 87 mins. For a group of Fujian teens, filming trysts and black-mailing wealthy "remittance widows" whose husbands are working abroad is a lucrative pastime...until they fall afoul of local mafia, snakeheads trafficking in human cargo. (Dragons and Tigers Prize, Vancouver Int’l Film Festival, 2007; Pusan Int’l Film Festival/PIFF post-production grant, 2007.)

In Love We Trust by director Wang Xiaoshuai. 2007. Mandarin with English subtitles. 115 mins. When their daughter is diagnosed with leukemia, a long-divorced couple deceive their new spouses and reunite to conceive a baby whose bone marrow may save their child's life. (Special Mention Jury Prize and Silver Bear Prize for Outstanding Screenplay, 2007 Berlin Film Festival. Nominated for Golden Bear.)

Tales of Rain and Magic by director Sun Xiaoru. 2006. Mandarin with English subtitles. 95 mins. This coming-of-age tale forms the first part of Sun's Trilogy of Women. (Screened at Rotterdam Int’l Film Festival, 2007.)

Shanghai Dreams (Qing Hong) by director Wang Xiaoshuai. 2005. Mandarin with English subtitles. 123 mins. It is 1983, and Chinese reform and opening is in full swing. The old generation of sent-down factory workers want to return to their urban hometowns, but their teenaged children - born and raised in the hinterlands - are reluctant to leave behind the only lives they've known. (Prix du Jury, Cannes Film Festival 2005. Nominated for Palm d'Or.)

Dream of the Bridal Chamber, by director Guo Baochang. 2005. Mandarin with English subtitles. 120 mins. Haunting melodies and lush cinematography inform this classic Peking Opera set to film.

Season of the Horse by director Ning Cai. 2004. Mongolian with English subtitles. 105 mins. In this elegy to a disappearing culture, a Mongolian herder loses his livelihood, sees his grazing lands fenced off and sells his horse to pay for his son's education. (NETPAC award and others; see here for more awards)

Pirated Copy by director He Jianjun (See also: Wiki entry). 2003. Screenplay: He Jianjun and Cui Zi’en (see also: Wiki and IMBD filmographies). Mandarin with English subtitles. 89 mins. The lives of motley characters intersect in Beijing, against a backdrop of pirated copies of western films.

Selected Scripts and Film Treatments

Realm of Gongs by director Yang Rui. 2009 documentary film treatment.

The Forbidden Book of Woman by director/screenwriter Sun Xiaoru. 2008 script treatment.

In Love We Trust by director/screenwriter

Wang Xiaoshuai. 2006 final-draft script. 98 pages. (Silver Bear for Outstanding Screenplay, Berlin Film Festival, 2007.)

Too Sexy for the Revolution by screenwriters Li Ying and Ai Wan. 2006 script treatment.

Leaving Camp Clearwater (Gaobie Jiabiangou) by director/screenwriter Wang Bing. 2005 full shooting script. 151 pages.

Aida of Wang Village by screenwriter Wang Shuo. 2004 first-draft script. 87 pages.

Chasing the Harvest by director/screenwriter He Jianjun. 2004 script treatment. 50 pages.

Selected Essays and Art Criticism

"Spectator Perspective" by Liu Sola; "Solution Scheme" by Shu Yang; "Autobiography in Two Parts" by Yu Na (in Solution Scheme by Xu Yong and Yu Na. 2007.)

"A Conversation between Ai Weiwei and Liu Xiaodong" (in The Richness of Life: Personal Photographs of Contemporary Chinese Artist Liu Xiaodong. Timezone 8 Books. 2007.)

"Photography as Visual Sociology: Xu Yong’s Tale of Two Cities" by Daozi; "Factography: The Photographic Work of Xu Yong" by Shu Yang (in Backdrops by Xu Yong. Timezone 8 Books. 2006.)

"Is 798 a Cultural Petting Zoo?" by Yin Jinan; other essays (in 798: A Photographic Journal. Editor: Zhu Yan. Timezone 8 Books. 2004.)

"Synthetic Reality" by Pi Li; other essays (in Synthetic Reality / Hecheng Xianshi. Editors: Ni Haifeng and Zhu Jia. Timezone 8 Books. 2004.)

"Cinema and Adam's Rib: An Analysis of Women's Roles in Chinese and Western Cinema" by Xiaolu Guo. 2001.

Theatre

Amber, a multi-media theatrical production by director Meng Jinghui and playwright Liao Yimei (translated full script and projection subtitles for 2005 performances in Beijing, Shanghai, Hong Kong and Singapore.)

Lyric translations

Too many to count. Folk favorites include Wild Children (野孩子), Hu Mage, Zhou Yunpeng and Buyi. Rock favorites include Second-Hand Rose (glam-rock, Dongbei style) and Cold Blooded Animal (psychedelic Sino-grunge; albums 1, 2 and 3.)

Book Publications

All Translations

The Paper Republic database exists for reference

purposes only. We are not the publisher of these works, are not

responsible for their contents, and cannot provide digital or paper

copies.

Posts

By Cindy M. Carter, July 29, '08

Claire Li's post on the Make Do Studios website analyzes some of the reasons Bertelsmann AG's business model failed in China:

"Why did Bertelsmann's China business fail? Some people say it has to do with the prevalence of pirated books here. But obviously, people who hold this view have not caught on to the state of the book market in China nowadays [...]

"Bertelsmann continued opening bookstores around the country without realizing how greatly the internet would influence people's shopping habits. People buy books on Dangdang and Joyo for its wide selection, low discounts, fast delivery, its payment-upon-receipt system, and freedom from any membership requirements like having to buy a book each month. Bertelsmann, by contrast, not only had a limited choice of books and poorer discounts, but it added another requirement last year that its platinum members had to spend RMB 299 per year or else be bumped down to a lower level. An understandable amendment, since the book club's overhead is high, but nobody wants to be forced to spend money."

read the complete article

Update: Another take on Bertelsmann's China venture (from Chen Gang, a journalist at China Publishing Today)

By Cindy M. Carter, July 9, '08

Xiao Ding sat at the narrow, cigarette-scarred wooden table with his head cradled on one arm, wondering whether or not he ought to scream. But of course, he didn't; he only went through the motions, noiselessly opening and closing, opening and closing his mouth. In the dim light of the bar, the faces of the hostesses clustered behind him looked sickly, almost green. Xiao Ding found himself distracted by their Sichuanese-accented chatter, drawn into their conversation and flung out again, like some traveler stranded on a highway bound for Sichuan.

He stood up and headed for the exit. As he passed the bar, the hostesses fell silent. One of the girls swiveled around to stare at him, her big, heavily-lipsticked mouth parted as if to speak. Xiao Ding gazed back at her uncomprehendingly, and took another step toward the door. Unable to hold back any longer, the large-mouthed girl called after him: Hey, you haven't paid your bill yet! Without bothering to answer, Xiao Ding reached the door and pushed it open, ushering in a wave of noontime summer heat. Seen from the perennial darkness of the tiny bar, the city outside was dazzling, a blaze of light. There were a few pedestrian stragglers, tongues lolling out of their mouths, panting in the heat. Xiao Ding surveyed the scene for a moment before allowing his hand fall to his side, and the door to swing closed on its spring hinge. He returned to his original seat and lit up a cigarette.

A short while later, the large-mouthed girl approached and handed him his check with feigned politeness: Excuse me, sir, but if you wouldn’t mind settling your bill...Why should I? Xiao Ding asked, an edge of hysteria to his voice. The hostess seemed startled: What do you mean, why? I mean why do I have to pay first? Xiao Ding demanded belligerently. Afraid I'm going to make a run for it, is that it? Shocked by his rudeness, the hostess began to stammer. The longer she stammered, the more pronounced her Sichuanese accent became. Xiao Ding was, if anything, even more shocked by his own behavior; he bowed his head and fidgeted uncomfortably. The hostess hesitated a moment and began to walk away, but Xiao Ding called her back and promptly paid the amount indicated on the bill. The moment the hostess had the money in hand, her fear seemed to dissipate. She turned away with a snort of derision and flounced back to the bar.

After this, Xiao Ding had no desire to remain in the bar, but if he left right away it would seem even more humiliating, like he'd been driven away. At that moment, he was seized by an overwhelming urge: Man, did he ever have to take a shit. The call of nature was a timely one for which he couldn’t help but feel grateful. As Xiao Ding stood up to leave, he experienced a moment of dizziness, and the room went black. He waited until the sensation had passed, then proceeded to grope his way to the back of the bar. Man, was this place ever dark. He located the restroom door and went inside, stopping in shock when he realized it wasn't a restroom at all, but an outside stairwell piled with construction debris. Naturally, he experienced an initial pang of disappointment at having made an exit when he had so clearly intended to make an entrance, but the stairwell was so hot—and his need to defecate now so intense—that he soon forgot about everything else. Fuck, he thought, at times like these, you might as well die and get it over with. Assuming he didn't intend to follow through on this and keel over on the spot, however, he had little choice but to follow the arrows on the wall and hope they led to a toilet.

Skirting a heap of broken ceramic tiles, Xiao Ding climbed the stairs to the second floor and made his way to an unbelievably filthy restroom at the end of the hallway. He quickly chose the stall that looked the cleanest—although it was still squalid beyond compare—and squatted over the hole. The stall was so tiny that he could hardly squat without his head touching the graffiti and sputum-covered wooden door. Xiao Ding tossed his hair and tried to take a step back, but found his retreat blocked by a pile of blackened and congealed feces. Gingerly, he reached out a hand and pushed open the wooden door to give himself more space. Across the way, he glimpsed a row of four yellowing urinals. The two far right urinals had been taped over with rough brown construction paper, upon which someone had scrawled in pencil: "Out of Order". As the stall door began to swing back of its own accord, Xiao Ding pushed it open, only to have it close again. Finally, he used his left hand to prop open the door.

As Xiao Ding labored to take a shit in the unbearable heat, the position proved too exhausting. He withdrew his hand and allowed the door to swing back and rest against his forehead. By now, his shirt and trousers were soaked with sweat and clinging to his skin like a plaster. The task he had hoped to complete as quickly and painlessly as possible seemed to be taking ages. To make matters worse, the scar on his belly was starting to itch again. Two flies buzzed around his head, and there wasn’t a damn thing he could do about them. After a while, his annoyance was replaced by a strange sense of familiarity, a feeling bordering on affection. Fuck, he thought, how come I never noticed before how close humans are to flies? At that moment, the flies seemed like pretty little songbirds, tiny buzzing pets he had been nurturing for years without even knowing.

Just then, someone opened the restroom door. Xiao Ding heard footsteps followed by a loud splash, as the newcomer trod in the puddle of stagnant water at the entrance. Xiao Ding glanced down at his own feet and saw that his cloth shoes were half-soaked. He heard the man cursing and stamping his feet as he walked over to the urinals. The familiar clink of a belt being unbuckled. A very long silence. No sound of urination. Locked in a stalemate with his own bowels, Xiao Ding could only squat passively in his stall and try to guess what was happening over at the urinals. As the silence stretched on, he began to get nervous; god only knew what sordid business the man might be getting up to. He certainly hadn't left the restroom, because his presence was palpable. Xiao Ding was tempted to open the wooden stall door and take a peek, but it seemed inappropriate, somehow.

At that moment, he was startled to hear the stranger speak: Fuck, can you believe this weather? This heat is murder, know what I mean? Xiao Ding wondered if there might be a third party in the restroom, although he could swear he'd heard only one person enter. When no one answered, the man repeated himself: This heat is murder, you know? Know what I mean? Xiao Ding experienced a moment of confusion. He plugged his nose and lowered his head to peek beneath the partitions on either side. Both stalls were empty. He must be talking to me, Xiao Ding thought, and answered grudgingly: Yeah, yeah, sure. Sighing, the stranger continued: It’s gotta be torture trying to take a shit in here. Worse than a fucking prison, eh? Wiping the sweat from his brow, Xiao Ding kept his reply perfunctory: Yeah, worse than a prison. He could hardly believe it when the man, apparently hell-bent on continuing the interrogation, pressed on: So why are you taking a shit, then? At this point, Xiao Ding was on the verge of pulling up his pants and leaving, but for some reason he answered the man automatically: N-no, see, I just happened to be passing by... Unsatisfied with this rather lame answer, Xiao Ding felt obliged to expand: Had I known what a pit this place was, I’d have never stopped in here to take a shit. The man gave a derisive snort: Fuck, I wasn't asking why you came in here to shit, I was asking why you'd bother to take a shit at all. By now, Xiao Ding's forehead was wet with perspiration. He wiped the sweat from his brow and flung it to the ground. His fingers grazed the floor and came away dripping with some unidentifiable goo. Recoiling in disgust, he reached out automatically for the toilet paper.

In that instant, Xiao Ding experienced two terrible realizations: (1) There was no toilet paper in the stall and (2) He had neglected to bring any of his own. Perspiring profusely and starting to panic, Xiao Ding raised himself on his haunches and patted his trouser pockets. But what was he hoping to find there? His trousers didn't even have pockets. So uh, why are you taking a shit? The man calmly repeated his question. Although Xiao Ding was now seething with fury, some small corner of his mind registered the fact that he might have to ask this rude stranger for a favor, and soon. He composed his response carefully. Um, what's that? he asked, trying to mask his annoyance, how do you mean? The stranger snorted again: Bet you forgot to bring toilet paper, didn't you? It's like they say: The wise man thinks of everything, but even a sage slips up now and then. Wow, how'd you know I forgot toilet paper? Xiao Ding answered. It's so weird that you knew. Just as he was about to push open the stall door and ask the man for a scrap of toilet paper, he felt his bowels begin to move. The urge to shit was overwhelming. Lowering his head and gritting his teeth, he tried desperately to hold back the flood. At the same time, he began mentally composing his plea for help. Ha, I knew it, I just knew it! the man exclaimed smugly. Xiao Ding heard several sharp staccato bursts of urine, followed by a long, satisfied groan. One of the buzzing flies alighted on his kneecap and sat there, as if pondering the same question as Xiao Ding. Just as Xiao Ding was about to ask the stranger for some toilet paper, the man beat him to the punch: Fuck, I'd like to see how you get out of here! Before Xiao Ding could react, the stranger bolted for the restroom door. Judging by the clatter, he’d nearly tripped over himself in his haste to make an exit. When the noise had subsided, a disheartened Xiao Ding raised a fist and pushed open the wooden stall door. The row of urinals across from him was unchanged, the restroom as seedy as ever, but the place was deserted.

By Cindy M. Carter, June 16, '08

This song, which appeared on Cui Jian's 1994 album "Balls Under the Red Flag" (红旗下的蛋) was the first Chinese song I ever attempted to translate. Many years and countless failed revisions later (and newly inspired by a documentary-in-progress about Chinese rock and roll), I've come back to it. As anthems go, it's pretty damned good...a political commentary cloaked in sexual imagery and double-entendre. If I had to reach for a western equivalent, I'd choose The Guess Who's "American Woman" and add a sprinkling of Bob Dylan, just for good measure.

I suspect that some of our translation colleagues have, at one time or another, translated this song into English and tucked it into their desk drawers. If so - if you're one of the proud, the reticent, the scholarly, the bored or the intrepid who have riffed this song and filed it away somewhere for posterity or inclement weather - please post your translation. The song raises some interesting language questions, and seems to defy most attempts at literal translation. As you can see, I've played these lyrics fast and loose.

Amnesty (宽容)

Both eyes closed, leaning on you

All hands down, stroking me

I want this satisfaction

and need you to respond

I want to tell you everything

just don't be mad with me

It's never love or hate with you

you're no more than what you are

I'm exhausted and it's pointless

but I have to go on fighting you

Fuck you, I say, fuck you

I'll talk behind your back

In the end, we'll see who wins

who holds out to the last

My eyes are open now and angry

I see what you've become and I can't speak

I want to sing an amnesty

for all that's happened here

but my voice sounds strange to me...

(click "more" for the Chinese lyrics)

More…

By Cindy M. Carter, May 23, '08

Historian and translator extraordinaire Jonathan Spence will give the prestigious 60th anniversary BBC Radio 4 Reith Lectures.

The series of four lectures, entitled Chinese Vistas, will be broadcast weekly at 9.00am on Radio 4, beginning on 3 June 2008. (Nice date for a lecture series on China, don't you think?)

See this press release for more info and links.

By Cindy M. Carter, May 9, '08

Although this may be of limited interest for those of you not resident in China, the recent confusion over visa renewals has caused some consternation in our circles, the little campfires around which yours truly, and her fellow translators-in-arms, are bivouacked.

Here’s a post from Danwei.org related to the great summer 2008 visa kerkuffle: Visa, visa, where are you.

You might ask why, in light of these changes, we translators don’t simply find a related day job or link up with some corporate sponsor willing to support our endeavors. The answer: there is no such thing as a company dedicated to literary translation in China. Ditto for film translation. Translation companies, such as they are, offer rates that fall tragically short of a living wage (particularly for our Chinese colleagues; we Chinese-to-English translators are somewhat better off), and they tend to focus on technical, legal, medical or commercial translation.

Advertising companies pay handsomely, but who wants to spend four or five hours per day convincing the Chinese populace to buy more cars/smoke more cigarettes/consume more meat, imported or domestic? Wages aside, there’s a way to be a person, and a person’s got to sleep. Besides, after a decade or so of studying Chinese, wouldn’t our time be better spent translating authors and filmmakers such as Yan Lianke, Li Er, Wang Xiaobo, Wang Xiaoshuai, Tian Zhuangzhuang or Luo Yan, rather than salvaging cheap ad copy for Audi, Pepsi, Avon, Budweiser or Ford?

A far more common option is to cadge or chivvy a friend or colleague into putting one on the books as a foreign hire, the recipient of a coveted “Z” work visa. In the short-term, it seems an easy solution...but keep in mind the old adage about favors: “The most expensive things in China are free.”

The upshot of this diatribe is that, effective July 7 of 2008, I honestly don’t know where I’ll be.

By Cindy M. Carter, May 6, '08

The May 4, 2008 edition of the New York Times Book Review features reviews of four new translations of Chinese novels:

- Mo Yan’s Life and Death are Wearing Me Out, translated by Howard Goldblatt

- Jiang Rong’s Wolf Totem, translated by Howard Goldblatt

- Wang Anyi’s The Song of Everlasting Sorrow, translated by Michael Berry and Susan Chan Egan (includes chapter excerpt)

- Yan Lianke’s Serve the People, translated by Julia Lovell (includes chapter excerpt)

One interesting, and rather humbling, note: the two books translated by Howard Goldblatt total 1067 English language pages. 1067 pages, people. As someone who counts herself lucky, very lucky, to get through 1000 characters of literary translation per day, I can’t imagine how he does it and still manages to find time to sleep. Damn, I could have/should have/would have asked him that at the Moganshan translation seminar…

(Thanks to fellow-translator Bruce Humes for giving us the heads-up on these reviews.)

By Cindy M. Carter, November 24, '07

Literature matters; music matters, too.

Here are some of the best Chinese videos and concert performances I've seen.

Artist: PK 14

Song: Tamen

hysterical video that knows how to take the piss and employ stock footage

Artist: Second Hand Rose

Song: New Tricks

amazing performance by China's best drag band - Beijing CD Cafe Club 2003

Artist: Second Hand Rose

Song: Survival

in the mean streets (hutongs?) of Beijing, sometimes you just can't win

Artist: SUBS / Brain Failure

SUBS and Brain Failure at MIDI

MIDI music festival interview with SUBS,

live concert performances by SUBS and Brain Failure

Artist: Su Yang

Song: The Phoenix

live performance of gorgeous song

(there's an animated video too, but it lacks the appropriate pathos)

Artist: XTX and Cold Blooded Animal

Song: Who was it who brought me here?

Yunnan Snow Mountain Music Festival performance with gu zheng and ginormous kick-ass fog machines (in those misty mountain climes, fog machines seem a bit redundant, don't they?)

Artist: XTX

Songs: Living Underground and Circling Sun

live concert footage from Xiao Suo's memorial

By Cindy M. Carter, November 12, '07

Just ran across some poems in the archives, early translations I thought I'd lost. The first three are from Gu Cheng's 2005 (posthumous) collection《走了一万一千里路》. The other poems are from a 1995 edition of Gu Cheng's collected works《顾城诗全编》- also posthumous. Pretty free-wheeling translations, but there are some good moments. I think there's something here everyone can joyfully disagree on...

Truisms

The vase says: I’m worth a thousand hammers.

The hammer says: I’ve smashed a hundred vases.

The artisan says: I’ve made a thousand hammers.

The master says: I’ve killed a hundred artisans.

The hammer says: I've bludgeoned one master to death.

The vase says: I now contain that master’s ashes.

More…

By Cindy M. Carter, August 9, '07

I'm blowing off deadlines left and right, so don't have time to do a full translation of this chapter. Even though I'm not really in the game, just wanted to toss in a few low-denomination chips and support the translation of this tremendously influential and unfairly neglected Chinese author....long live Wang Xiaobo! And wansui to Brendan, Eric and Feng37 for bringing his words to life.

Her reasoning went like this: although everyone said that she was a slut, Chen Qingyang felt that she was not, because to be a slut you had to sleep around, and she had never slept around. Although her husband had been in jail for over a year, she had never slept around in his absence, nor had she slept around prior to his imprisonment. For this reason, Chen Qingyang simply couldn't understand why people insisted on calling her a slut.

More…

By Cindy M. Carter, July 20, '07

Back in 1990, long before I had even begun studying Chinese, I remember Chalmers Johnson - in an undergraduate politics class about revolution, of all things - commenting that "the Chinese have a very scatological sense of humour." At the time, I had no reference point, no way of assessing the veracity of his claim, so I chalked it up to the amiable ramblings of a brilliant professor lulled to boredom by sleepy undergraduates, San Diego's balmy clime and the interminable weight of tenure.

Now, 17 years later, I find myself working on three excerpts by three very different Chinese authors - Yu Hua, Zhu Wen and Li Er - that have inspired me to revisit Chalmers Johnson's observation. In each of these passages, feces plays a starring role. While I'm in no mood to make generalizations about scatology or humour in China, this is marvelous excuse to introduce translations from a few favorite authors.

Yu Hua's Brothers

Protagonist Li ("Baldy") Guangtou sits atop his gold-plated toilet dreaming of his impending voyage into space on a Russian civilian shuttle and remembering his youth. Oh, the hazy crazy days of peeping at female asses through the partition of a public toilet...

Zhu Wen's What is Love and What is Garbage:

On the worst day of his life, protagonist Xiao Ding finds himself (1) the laughingstock of bar hostesses (2) a refugee who flees a bar only to enter the most ungodly toilet imaginable (3) a man without a shred of toilet paper (4) the butt of a prank by an unkind stranger standing at the urinals. On days like this, you might as well just call it quits...

Li Er's Truth and Variations:

While some might see Doctor Bai as a freak or a fetishist, he is in fact an expert in all things excremental: a scholar of shit, a doyen of dung, a professor of piddle, piss and poop. We say this with all due respect to his academic background, interests and credentials.

More…

By Cindy M. Carter, July 1, '07

As you can see, we're still in the process of construction - adding slowly but steadily to our database of books and authors. Worth a look are two recent additions to our author database:

Author: Li Er (postings from Cindy)

Truth and Variations (novel)

The Pomegranate Tree Sprouts a Cherry (novel)

Author: Feng Tang (postings from Eric)

Given a Girl at Age 18 (novel)

Everything Grows (novel)

By Cindy M. Carter, June 29, '07

Bashi Niandai Fangtanlu (八十年代访谈录), Sanlian Shudian, 2006. 453 pages.

With a roster of interviewees that includes poet Bei Dao, author Ah Cheng, rock musician Cui Jian and filmmaker Tian Zhuangzhuang, Zha Jianying looks back on the cultural, artistic and social legacy of 1980s mainland China. Essential reading for anyone interested in contemporary China, the book is also filled with fascinating trivia: Who knew that poet/essayist Mang Ke once worked in a paper factory? Or that before cycling around Beijing to make their deliveries, he and the other founders of the influential samizdat literary magazine “Today” took the precaution of altering their bicycle license plates in case they had to make a quick getaway? The interviews are generally very frank, and yield some candid admissions (film critic Lin Xudong’s reservations about Jiang Wen’s films, for example, or his championing of Wang Bing’s “West of Tracks” and Jia Zhangke’s “Xiao Wu” as the two finest Chinese films to emerge in this decade) as well as some startling omissions (Bei Dao’s refusal to discuss contemporary Chinese poetry in any detail).

Unfortunately, the book is not yet available in English translation. Here is a blurb (translation mine) from Zha Jianying’s e-mail interview with poet Bei Dao:

Zha Jianying: Some contend that the 1980s were an era of mainland Chinese idealism, and that the present age is one of pragmatism and materialism - an era in which the vast majority of mainland Chinese intellectuals, artists and writers have either been co-opted by the status quo, seduced by wealth and fame, or simply lulled by the prospect of security and respectability. Would you agree with this assessment? In commenting about a Chinese artist who had traded in a rebellious youth for a career in business, you once wrote: “In the end, commerce trumps everything.” Do you think that the commercialization of our society has eroded rather than nourished, corrupted rather than sustained, contemporary Chinese art and literature?

Bei Dao: I think that’s a bit of an oversimplification. The 1980s posed their own problems; they also gave rise to the 1990s crisis. What you’re implying is that the idealism of the eighties failed to take root. In the 1980s, intellectuals born and raised during the Chinese Cultural Revolution were just beginning to make their mark, but they had yet to establish their own traditions. Nor had they managed to overcome the obstacles that prevented them from carrying on the traditions of the May Fourth Movement (1919), a period in history that constitutes a cultural lifeline for Chinese intellectuals. Any nation in the process of modernization will, at some point, be afflicted by commercialization. The question is: how do we maintain our principles in such a constantly shifting environment?

Zha Jianying: Do you ever feel nostalgic for the 1980s? What are your hopes for the future of Chinese poetry?

Bei Dao: No matter what, I will always feel a certain nostalgia for the 1980s, despite the various crises we weathered. Every nation prides itself on a certain cultural or literary high watermark: the “silver age” of Russian literature in the early 20th century is but one example. I think that the 1980s represented the high point of 20th century Chinese culture. I fear that we may have a long wait before we see such a flowering again, and that our generation may not live to see it. The renaissance of Chinese art and literature in the 1980s grew out of the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and 1970s. As the saying goes, “seismic cataclysms unearth new springs”; were it not for the Cultural Revolution, the eighties would never have played out the way they did. But more important is the way the curtain fell: in the tragi-heroic finale to the 1980s, we witnessed the vitality of an ancient culture, its aesthetic and artistic significance and its latent potential. For all these reasons and more, we have just cause to be proud.

By Cindy M. Carter, June 24, '07

Just bought Li Hongqi's novel "Lucky Bastard" (李红旗 《幸运儿》). It was the back cover blurbs that caught my eye: high praise from Han Dong and Zhu Wen; few first-time Chinese authors can ask for better that that.

In Zhu Wen's amusing preface to the book, he admits that although he has been "lazy" about writing lately, he was pleased to write a few paragraphs on behalf of Li Hongqi, a young poet-novelist who first came to Zhu Wen's attention with his poem "Friends".

I liked "Friends" so much that I translated it on the spot:

Poem: Friends

Poet: Li Hongqi

In the autumn of 1994,

many people were engaged

in the study of sexual intercourse.

That's about the time I learned it.

Naturally, prior to that autumn

there were a good many people

who'd been having intercourse for years,

and of course a whole lot more

who hadn't mastered it,

even by the autumn of 1994.

If all those interested alumni

of the sexual intercourse

circa autumn 1994

could only find some way

to re-establish contact

with one another,

who knows...

everyone might just end up

making a friend.

(Click "more" to see the original poem in Chinese)

More…

By Cindy M. Carter, June 13, '07

This may be beyond the ken of our literary website, but singer Liang Long (of the Chinese rock band Second Hand Rose) writes some of the wittiest, most cunning lyrics around. Here's a sample translation, good fun for all. Click for posting that includes both Chinese lyrics and English lyrics in translation:

"Let the Artists [be the first to strike it rich]"

...I’m a packet of STD meds

That the spouse opens when your back is turned

I’m a demigod who broke all of heaven’s rules

And got kicked back down to earth...

More…

By Cindy M. Carter, June 12, '07

A very short translated excerpt from the first page of Yan Lianke's 2006 novel, Dream of Ding Village (丁庄梦). When he is at his best, Yan is an extraordinarily lyrical writer who uses rhyme, rhythm, repetition and cadence to great effect. The first chapter of Dream of Ding Village is a joy to read aloud in Chinese - musical and prose-poetic, it establishes the tone of the entire novel and introduces refrains that the author returns to again and again. I am not sure that I have done this justice in my translation, but it is a labor of love and a work in progress.

"A day in late autumn, a late autumn dusk, the dusk of a late autumn day. Because of the autumn, because of the dusk, the sun that sets above the East Henan plain bloods up into a ball, making red of earth and sky..."

More…