Cindy M. Carter 辛迪

worldcat |

contact

Cindy M. Carter is a Beijing-based American translator of Chinese fiction and film. Since coming to China in 1996, she has translated over 50 award-winning independent Chinese films and documentaries, dozens of scripts, short stories, essays and poems and 2 novels. She is currently the in-house translator and editor at Ullens Center for Contemporary Art (UCCA) in 798 Art District, Beijing.

Fiction

Dream of Ding Village by Yan Lianke. 2011. Constable and Robinson (UK) / Text Publishing (Australia) / Grove Press (US). 352 pages. Prose-poetic tale of blood-selling, AIDS, profiteering and revenge set in rural Henan. (Long-listed for the 2012 Man Asian Literary Prize.)

"But the sickness had only just begun. [...] The real explosion wouldn't come until next year, or the year after next. That's when people would start dying like sparrows, or moths, or ants. Right now they were dying like dogs, and everyone knows that in this world, people care a lot more about dogs than they do about sparrows, moths or ants."

Village of Stone by Guo Xiaolu. 2004. Chatto & Windus, U.K. 181 pages.

Fictional memoir of a young woman coming to terms with repressed memories of her childhood in a Chinese fishing village. (Short-listed for the 2005 Independent Foreign Fiction Prize; Long-listed for the 2005 Dublin IMPAC Prize.)

"The Village of Stone was my entire world, my fortress without windows, a place where they had dug my grave almost as soon as I was born."

"Two people together never add up to anything more than one person added to another. That we continue to add ourselves up in this way is the reason human beings will always be lonely."

Selected Documentaries

Karamay by director Xu Xin. 2009. Mandarin with English subtitles. 371 mins. In 1994, over 450 people - mainly schoolchildren and their teachers - were killed or injured when a fire broke out in a theatre in Karamay city, Xinjiang province (see Wiki entry). The survivors, who had been attending a song-and-dance performance to entertain visiting cadres, reported that students were instructed to remain in their seats so that VIPS and party cadres could exit first. Through rare video footage and first-person interviews with families and survivors, Xu Xin documents how the story was portrayed in the official media, the public anger that erupted after the fire and the community's 15-year quest for justice.

WE: Creatures of Politics, Voices of Conscience by director Huang Wenhai. 2008. Mandarin with English subtitles. 102 mins. In the run-up to the 2008 Beijing Olympics, several generations of activists debate the future of political reform and human rights in China. (Special Jury Prize, Venice Film Festival, 2008; Screened at One World Human Rights Festival, 2009.)

Crime and Punishment by director Zhao Liang. 2007. Mandarin and dialect with English subtitles. 123 mins. Young military police patrolling the border between China and North Korea deal with career frustration and local disputes ranging from petty theft to illegal logging to false dead-body reports. (Best Documentary, Nantes Festival des Trois Continents, 2007; Best Director, One World Int'l Human Rights Film Festival, 2007.)

Fairytale, by producer Ai Weiwei. 2007. English, German, Mandarin and dialect with English subtitles. 9 hours. With 16 directors and a crew of 8 translators, Fairytale offers a behind-the-scenes look at artist Ai Weiwei's ambitious project to bring 1001 Chinese people from various walks of life to the 2007 Kassel Documenta in Germany. Subjects include: a policeman-turned-blogger who was refused a passport for his blog posts critical of Chinese law enforcement, a pair of writers whose passion for poetry and fondness for drink goes hand in hand, and a group of farmers whose trip to Kassel will be the first time they've left their village, much less their country.

Fengming: A Chinese Memoir (alt title: Chronicle of a Chinese Woman) by director Wang Bing. 2007. Mandarin with English subtitles. 184 mins. He Fengming speaks directly to the camera of her experiences as a revolutionary, journalist, accused rightist, prison camp inmate and chronicler of more than a half-century of Chinese history. (Grand Prize, Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival 2007; Young Critics Award, Cinema Digital Seoul, 2007.)

Mona Lisa by director Li Ying. 2005. Mandarin with English subtitles. 110 mins. 20 years after being kidnapped as a child-bride, a young woman named Xiuxiu manages to locate her birth parents and lands her kidnappers - the couple who raised her - in prison. Motivated by a sense of responsibility to her adoptive siblings, Xiuxiu tries to get her adoptive mother released on furlough.

Before the Flood by directors Yan Yu and Li Yifan. 2004. Sichuan dialect with English subtitles. 143 mins. As the flood waters of the Three Gorges Dam Project rise, dislocated residents of the ancient town of Fengjie clash with local cadres and try to find new lodgings. (Grand Prize, Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival, 2005; Best Documentary Feature, Lisbon Int'l Documentary Film Festival, 2005; Winner, International Competition, 2005 Cinéma du Réel Film Festival; Wolfgang Staudte Prize, Berlin Film Festival, 2005; Humanitarian Prize, Hong Kong Film Festival, 2005.)

West of Tracks by director Wang Bing. 2003. Mandarin and Shenyang dialect with English subtitles. 545 mins. Sweeping three-part documentary (I: Rust, II: Remnants, III: Rails) depicts the lives of laid-off factory workers and their children in Shenyang, China's rust belt. (Best Documentary Feature, Mexico City Film Festival, 2005; Grand Prix, Marseille Festival of Documentary Film, 2003; Grand Prize, Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival, 2003; Golden Montgolfier Award, Nantes Festival des Trois Continents, 2003; European DVD release: MK2 films.)

Paper Airplane by director Zhao Liang. 2001. Mandarin with English subtitles. 89 mins. Gritty documentary about heroin addiction and the Beijing underground music scene. A film that made the subject matter less taboo - and inspired numerous feature-film knockoffs - it's still the only one that gets the story right. (Merit Prize, Taiwan International Documentary Festival, 2002.)

Selected Feature Films

Fujian Blue, (See also: Wiki entry) by director Robin Weng (Weng Shouming). 2007. Fujian dialect with English subtitles. 87 mins. For a group of Fujian teens, filming trysts and black-mailing wealthy "remittance widows" whose husbands are working abroad is a lucrative pastime...until they fall afoul of local mafia, snakeheads trafficking in human cargo. (Dragons and Tigers Prize, Vancouver Int’l Film Festival, 2007; Pusan Int’l Film Festival/PIFF post-production grant, 2007.)

In Love We Trust by director Wang Xiaoshuai. 2007. Mandarin with English subtitles. 115 mins. When their daughter is diagnosed with leukemia, a long-divorced couple deceive their new spouses and reunite to conceive a baby whose bone marrow may save their child's life. (Special Mention Jury Prize and Silver Bear Prize for Outstanding Screenplay, 2007 Berlin Film Festival. Nominated for Golden Bear.)

Tales of Rain and Magic by director Sun Xiaoru. 2006. Mandarin with English subtitles. 95 mins. This coming-of-age tale forms the first part of Sun's Trilogy of Women. (Screened at Rotterdam Int’l Film Festival, 2007.)

Shanghai Dreams (Qing Hong) by director Wang Xiaoshuai. 2005. Mandarin with English subtitles. 123 mins. It is 1983, and Chinese reform and opening is in full swing. The old generation of sent-down factory workers want to return to their urban hometowns, but their teenaged children - born and raised in the hinterlands - are reluctant to leave behind the only lives they've known. (Prix du Jury, Cannes Film Festival 2005. Nominated for Palm d'Or.)

Dream of the Bridal Chamber, by director Guo Baochang. 2005. Mandarin with English subtitles. 120 mins. Haunting melodies and lush cinematography inform this classic Peking Opera set to film.

Season of the Horse by director Ning Cai. 2004. Mongolian with English subtitles. 105 mins. In this elegy to a disappearing culture, a Mongolian herder loses his livelihood, sees his grazing lands fenced off and sells his horse to pay for his son's education. (NETPAC award and others; see here for more awards)

Pirated Copy by director He Jianjun (See also: Wiki entry). 2003. Screenplay: He Jianjun and Cui Zi’en (see also: Wiki and IMBD filmographies). Mandarin with English subtitles. 89 mins. The lives of motley characters intersect in Beijing, against a backdrop of pirated copies of western films.

Selected Scripts and Film Treatments

Realm of Gongs by director Yang Rui. 2009 documentary film treatment.

The Forbidden Book of Woman by director/screenwriter Sun Xiaoru. 2008 script treatment.

In Love We Trust by director/screenwriter

Wang Xiaoshuai. 2006 final-draft script. 98 pages. (Silver Bear for Outstanding Screenplay, Berlin Film Festival, 2007.)

Too Sexy for the Revolution by screenwriters Li Ying and Ai Wan. 2006 script treatment.

Leaving Camp Clearwater (Gaobie Jiabiangou) by director/screenwriter Wang Bing. 2005 full shooting script. 151 pages.

Aida of Wang Village by screenwriter Wang Shuo. 2004 first-draft script. 87 pages.

Chasing the Harvest by director/screenwriter He Jianjun. 2004 script treatment. 50 pages.

Selected Essays and Art Criticism

"Spectator Perspective" by Liu Sola; "Solution Scheme" by Shu Yang; "Autobiography in Two Parts" by Yu Na (in Solution Scheme by Xu Yong and Yu Na. 2007.)

"A Conversation between Ai Weiwei and Liu Xiaodong" (in The Richness of Life: Personal Photographs of Contemporary Chinese Artist Liu Xiaodong. Timezone 8 Books. 2007.)

"Photography as Visual Sociology: Xu Yong’s Tale of Two Cities" by Daozi; "Factography: The Photographic Work of Xu Yong" by Shu Yang (in Backdrops by Xu Yong. Timezone 8 Books. 2006.)

"Is 798 a Cultural Petting Zoo?" by Yin Jinan; other essays (in 798: A Photographic Journal. Editor: Zhu Yan. Timezone 8 Books. 2004.)

"Synthetic Reality" by Pi Li; other essays (in Synthetic Reality / Hecheng Xianshi. Editors: Ni Haifeng and Zhu Jia. Timezone 8 Books. 2004.)

"Cinema and Adam's Rib: An Analysis of Women's Roles in Chinese and Western Cinema" by Xiaolu Guo. 2001.

Theatre

Amber, a multi-media theatrical production by director Meng Jinghui and playwright Liao Yimei (translated full script and projection subtitles for 2005 performances in Beijing, Shanghai, Hong Kong and Singapore.)

Lyric translations

Too many to count. Folk favorites include Wild Children (野孩子), Hu Mage, Zhou Yunpeng and Buyi. Rock favorites include Second-Hand Rose (glam-rock, Dongbei style) and Cold Blooded Animal (psychedelic Sino-grunge; albums 1, 2 and 3.)

Book Publications

All Translations

The Paper Republic database exists for reference

purposes only. We are not the publisher of these works, are not

responsible for their contents, and cannot provide digital or paper

copies.

Posts

By Cindy M. Carter, December 30, '09

According to the 2009 translation database compiled by the literary website Three Percent, there were 348 new translations of fiction and poetry (283 novels and short-story collections; 65 volumes of poetry) on American bookshelves this year. Of the 348 works of literature to reach America from distant shores, only 10 were penned by Chinese authors. One, Dai Sijie's Once on a Moonless Night, was translated from the French. Another - In Such Hard Times: The Poetry of Wei Ying-wu - is a collection of poetry written during the Tang Dynasty. Yang Xianhui's Woman From Shanghai: Tales of Survival from a Chinese Labor Camp, although well worth reading, is a collection of eyewitness accounts presented as fiction (or semi-fictionalized) in order to elude Chinese censors. That leaves us with a total of 7 contemporary Chinese novels translated into English for the American literary marketplace in 2009. Seven. Books. From China. To America.

Compare this to the stats for other translations from various languages published in the U.S. this year: 59 from Spanish, 51 from French, 31 from German, 22 from Arabic (a mark of progress), 18 from Italian, 18 from Japanese, etcetera.

Here's the link to the Three Percent translation databases for 2009 and 2010. And a nice little pie-chart from The Faster Times ("What Are We Translating From?") illustrating the languages from which the 348 books were translated. Chinese works form a minuscule slice of an embarrassingly tiny pie.

Since there were so few Chinese offerings published in the U.S. this year, I can easily list them all here:

-

Banished! by Han Dong, translated by Nicky Harman. University of Hawaii Press.

-

Brothers by Yu Hua, translated by Eileen Chow and Carlos Rojas. Pantheon.

-

English by Wang Gang, translated by Martin Merz and Jane Weizhen Pan. Viking.

-

Five Spice Street by Can Xue, translated by Karen Gernant and Chen Zeping. Yale University Press.

-

Feathered Serpent by Xu Xiaobin, translated by John Howard-Gibbon and Joanne Wang. Atria.

-

In Such Hard Times: The Poetry of Wei Ying-wu, translated by Red Pine. Copper Canyon Press.

-

The Moon Opera by Bi Feiyu, translated by Howard Goldblatt and Sylvia Li-chun Lin. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

-

Once on a Moonless Night, by Dai Sijie, translated from the French by Adriana Hunter. Knopf.

-

There's Nothing I Can Do When I Think of You Late at Night, by Cao Naiqian, translated by John Balcom. Columbia University Press.

-

Woman From Shanghai: Tales of Survival from a Chinese Labor Camp by Yang Xianhui, translated by Huang Wen. Pantheon.

By Cindy M. Carter, December 15, '09

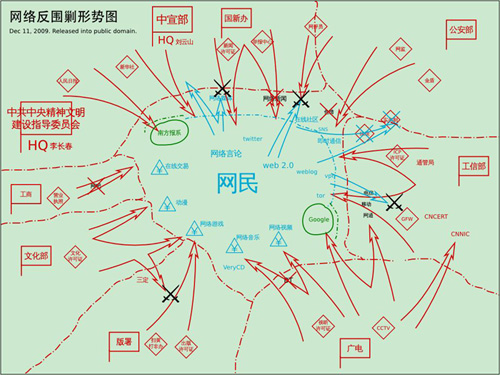

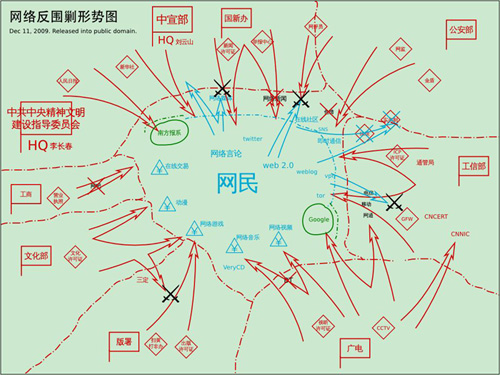

Chinese blogs, social networking sites and bulletin boards are buzzing about a humorous map of China's "Internet topography" that illustrates how China's netizens (网民, wangmin) are currently under attack from all sides. The title of the map (clever cartographer unknown) reads 网络反围剿形势图, which translates roughly as "A topographical map of resistance to [the campaign of] Internet encirclement and annihilation". Sounds clunky, I know, but it's a riff on a 1930's campaign by Chiang Kaishek and the Nationalists to encircle and wipe out communist base camps (see Wiki entry for more about the encirclement campaigns).

(Here's a larger version of the map.)

Sorry I don't have the Photoshop chops to annotate this map in English, but here are the salient details:

(1) In the center, we see China's netizens (网民) and their territory, indicated in blue. Strongholds include Google, Tor, VPN, weblogs, Web 2.0, Twitter, online speech, social networking, online music, online games, etc.

(2) On the periphery, in red, we see the territory held by various Chinese government bureaus and ministries. Red arrows indicate official encroachments; crossed swords represent recent battlegrounds; blue arrows show where China's Internet users have managed to strike back effectively.

(3) The top left is occupied by the HQ of the Spiritual Civilization Development Steering Commission (中共中央精神文明建设指导委员会), the Propaganda Department (中宣部, or 中共中央宣传部) and the State Council Information Office, SCIO (国新办, or 国务院新闻办公室), all of which are under the control of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCCPC).

Moving clockwise, we pass through the fiefdoms of the Ministry of Public Security (公安部); the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (工信部, or 工业和信息化部); SARFT, the State Administration of Radio, Film and Television(广电, or 国家广播电影电视总局); GAPP, the General Administration for Press and Publications (版署, or 新闻出版总署); MOC, the Ministry of Culture (文化部) and SAIC, the State Administration for Industry and Commerce (工商, or 工商行政管理总局). Note the red arrows coming from all directions, targeting the small blue corps.

(4) Bureaucratic turf wars: the pair of crossed swords at bottom left shows where the Ministry of Culture and GAPP have clashed over jurisdiction. The red arrows emanating from bottom right illustrate SARFT encroachments into Ministry of Industry and Infotech territory.

Somebody should make a t-shirt of this.

By Cindy M. Carter, December 2, '09

I have to admit: I've often dismissed (and sometimes dissed) the generation of Chinese writers born in the 1980s. There were so many prodigies, kids who started publishing not long after they became pubescent. Clearly, there was some precocious talent, but by the second or third book, you had to wonder if these teenage authors had experienced enough of life to be able to write about it.

I'm not asking that question anymore. The kids have come of age. They're in their mid- to late-twenties now, they've got a different attitude than their predecessors, they're blogging, and they're definitely writing some things worth reading.

I've been following the post-80's writers for a while now, and am finally seeing some things that knock my socks off.

Here are some short bits from two authors, both born in 1982. Zhang Yueran has been writing since she was 14; Han Han published his first novel when he was 17. Both are among China's most popular writers, and have sold millions (probably closer to tens of millions) of books between them.

Han Han, in response to how he feels about being a "public intellectual":

"Being a public intellectual is a lot like being a public toilet. Anyone can stop by and take a piss for free, and they don't have to clean up afterward. If you try to charge them 50 cents for toilet paper, they'll bitch about it and start kicking at your walls. But a city's got to have public toilets, otherwise people just crap in the streets. It's a pretty pathetic role sometimes, but if everyone in the city, even those who have their own bathrooms at home, comes to take a dump in the public toilet, well then... maybe there's some hope for this society yet."

Zhang Yueran, in her recent short story "Gone Astray":

"I could tell right away that Lin was a kindred spirit. Meeting him made me realize that two 'kindred spirits' need not necessarily like each other. I wasn't even sure if I'd want him as a friend, but I had to admit we had a lot in common. Lin was older than I'd expected, forty at least, small and rather scrawny. But he didn't seem to have been born that way: it was more like a lifetime of disappointment had whittled him down to size."

By Cindy M. Carter, December 1, '09

Maybe it's a meaningless list based on dubious statistics, but it's still fun. There are the usual popular authors, with a strong showing from writers of children's books and young adult literature. Nice to see some very worthy and serious authors on the list this year: Wang Meng, Yan Lianke and Alai, among others. To paraphrase Deng Xiaoping, 让部分作家先富起来 ("Let some of the writers become wealthy first.")

The highest-paid authors in China, 2009 edition

By Cindy M. Carter, November 29, '09

I couldn't resist this one. Joel Martinsen of Danwei.org castigates, illuminates and pulls out some photos from the archives to illustrate past slogans from the Gate of Heavenly Peas.

(Here's a link to the same, if you're blocked by the ornamental firewall.)

"Gross [of online magazine Slate] must have a particularly lousy tour guide. First he can’t manage to find a chocolate bar anywhere in China, and now he’s suggesting that explicit mentions of Marx and Lenin once adorned Tiananmen Gate..."

I loved this pre-revolutionary Tiananmen Gate slogan - apparently a favorite phrase of Sun Yatsen's - taken from the Book of Rites:

“The world belongs to the people” (Tianxia weigong / 天下为公)

A question for our translators: this phrase clearly means that each and every one of us has some share in this world, that even the humblest among us is entitled to some piece of the communal pie. But is there any implication of a corresponding obligation, any sense that those who partake of it should also contribute to "building" the pie? I've often wondered about the range of those two characters weigong / 为公. Look forward to hearing your thoughts.

By Cindy M. Carter, October 27, '09

"Jia Pingwa's books contain a lot of Shaanxi dialect that we Mandarin-speakers don't understand, dialect that foreigners are even less likely to understand. Another example is Yan Lianke's Shouhuo [The Joy of Living]. The translation rights were sold in 2004, but the book has yet to appear in translation. The reason is that they can't translate it - they just don't understand the dialect."

-- Southern Weekend (Nanfang Zhoumo) interview with Wu Wei, deputy director of the State Council Information Office and head of China Books International

(This follows an earlier comment thread found here.)

I wouldn't underestimate the importance of Wu Wei's comment. It may have been an off-the-cuff remark, but it came from the head of China's book export program, from the person who is supposed to be the face of Chinese literature abroad. If Wu Wei truly believes what she says, she is either a liar or a fool or both.

The foreign-language translations of Jia Pingwa's Feidu/Abandoned Capital and Yan Lianke's Shouhuo/The Joy of Living were NOT delayed because of a lack of good translators, or a dearth of foreign-type people who couldn't understand the dialect. We need to make this clear.

When I hear these pronouncements from Chinese officials, it reeks of xenophobia and makes my skin crawl. When I hear them from China-based corporate talking heads, it reeks of privileged expatriate insularity and makes me want to tear off talking heads (Jo Lusby, Penguin China: “The main challenges are ensuring good translations...” “The greatest problem is finding a good translator. It lives and dies simply in the translation...”).

Yes, yes, yes...books live and die in the translation...so why don't you cadres or talking heads ever deign to pick up the phone and actually speak to one of the up-and-coming generation of China-based translators who live in your city? When was the last time you managed to come up with an advance sufficient to support the translation of a 300 or 400-page novel? How long could YOU survive on an advance of a few thousand dollars? When will the parties who stand to profit from books in translation start pulling their weight? You get what you pay for, my friends, and you reap what you sow.

The reasons Jia Pingwa and Yan Lianke's works weren't translated earlier are complex. Some of their books were banned or appeared in expurgated versions in China. As such, they didn't make the best-seller lists. They didn't appear on the radar of foreign publishers soon enough. When they did, publishers jumped on the most controversial banned works (Serve the People, which is to Yan Lianke what The Names is to Don DeLillo) without regard to literary quality. The advances were abysmally low, so the translators had to borrow money, dig into their own pockets or rush the translations (sometimes all of the above). The foreign-language sales were disappointing, thus reinforcing the perception that Chinese fiction is a loss-leader in English-language markets.

But I don't believe it has to be this way. I think there has to be a better way.

2010 will mark the largest crop of emerging Chinese-to-English translators the world has ever seen. 2010 will be an amazing year in Chinese fiction, poetry, music and film. So why is no one buying?

By Cindy M. Carter, October 20, '09

Wanted to to share a few short passages from Yan Lianke's novel. The first is a dream sequence; the second, a poem. The translation is almost finished. Only a week to go, as I race toward the finish line (and try not to stumble).

-C

The night the tomb was robbed, grandpa had a dream:

The sky was filled with bright red suns. There were five, six, seven, eight, nine of them, crowding the sky and scorching the plain below. Drought had left the soil parched and cracked. Across the plain and well beyond, crops had died, wells run dry and rivers vanished. In an effort to banish the suns from the sky, to rid the sky of all the suns but one, strong young men had been chosen from each village, one man for every ten villagers. Armed with pitchforks, spades and scythes, they chased the suns across the plain, trying to drive them to the ends of the earth, topple them from the sky, and toss them into the ocean. Because surely, one sun in the sky was enough.

As grandpa stood at the entrance to the burial chamber, he remembered a bit of doggerel he'd heard as a child. It was an old folk saying here on the plain, a truism passed from generation to generation:

When graves are robbed of treasure,

there's not enough treasure to go around.

When graves are robbed of coffins,

there are too many coffins to be found.

By Cindy M. Carter, August 22, '09

The Guardian reports that Jean-Jacques Annaud will be directing the film adaptation of the novel Wolf Totem by author Lu Jiamin - better known by his pen name of Jiang Rong. (See full article).

A quote from the Guardian piece:

The Associated Press reported that Annaud would be forced to make an apolitical interpretation of the novel in order to pass Chinese film censorship, with the Beijing Forbidden City Film Company's statement about the project avoiding the book's political messages to describe it as "an environmental protection-themed novel about the relationship between man and nature, man and animal".

This sounds like the real deal, but it does bring back some memories: anyone recall a few years back, when rumours of a Peter Jackson/Weta adaptation of Wolf Totem were flying fast and furious? One imagines that the Jackson version would have been heavy on computer graphics and special effects, while Annaud plans to spend 18 months raising and training the wolves himself.

I'm curious about the screenplay adaptation. Will it be based on the French translation of the novel (Le Totem du loup, by translators Yan Hansheng and Lisa Carducci), or the English translation by Howard Goldblatt, or will they start from scratch and work up a screenplay based on the Chinese novel? Will the film itself have Mongolian dialogue, or Chinese, or both? Not English or French, certainly.

I'm sure we'll be hearing more about this in the months to come...

By Cindy M. Carter, June 29, '09

Some folks document contemporary Chinese society with words. Others do it with photography, visual art, music or film. At Paper Republic, we tend to focus on the wordsmiths: the novelists, essayists and poets who form the landscape of Chinese literature, and help to shape our perceptions of modern China.

But some of the most daring work in China today is being done by independent documentarians, guerrilla filmmakers armed with newly-affordable digital cameras, laptop computers and editing software. They tend to work alone, on shoestring budgets, outside the state-owned studio distribution system and - perhaps more importantly - beyond the reach of censors. And they're not the cast-offs, people who couldn't cut it the world of mainstream film: many are graduates of the Beijing Film Academy, alumni of China Central Television (CCTV), accomplished directors or cinematographers who left lucrative commercial careers to make the kind of films they always wanted to.

One of these days, we'll have a section on Paper Republic about Chinese indie film. Maybe we'll call it Digital Republic. In the meantime, my little bio of film work includes synopses of 15 outstanding documentaries and feature films from the last 8 years, with links to directors (photos/bios/filmographies), film festival awards and reviews in industry publications. Some of the highlights:

Wang Bing - continuing "his run as one of the world's supreme doc filmmakers with Fengming: A Chinese Memoir." (Variety)

Zhao Liang - whose Crime and Punishment "cements China's position as a doc powerhouse" (Variety), says that sometimes he feels "like I’m stealing from the people I shoot. It’s their life that has given me the inspiration to create, and that’s why I feel guilty."

Li Ying - who was forced to relocate his production company offices in Tokyo after receiving right-wing death threats related to his film Yasukuni, a controversial documentary about Japan's Yasukuni Shrine. Although the film was expected to sail through the Chinese censorship process, it has yet to be approved for theatrical release in China.

Cui Zi'en - author, director and university professor widely hailed as one of the pioneers of Chinese queer cinema.

And those are just the filmmakers I've translated, the ones who happened to make the list. Here are some other outstanding documentary directors, not to be missed:

Du Haibin: Along the Railway, Beautiful Men, Umbrella

Wu Wenguang: Bumming in Beijing, Dances with Migrant Workers, Fuck Cinema!

Yang Lina: Old Men, Home Video, The Love of Mr. An

Ni Zhen: Graduation, Postscript

Duan Jinchuan: The Square, No.16 Barkhor Street

Zhang Yuan: The Square, Demolition and Relocation, Crazy English

Yu Guangyi: The Last Lumberjacks, Survival Song

Luo Jian/Jiang Ping: Tale of Zhou

By Cindy M. Carter, May 29, '09

There's a song that's been making its way around the Internet: Zhou Yunpeng's "Don't Ever Be a Chinese Child"

(不要做中國人的孩子 by 周云蓬) - if the above link is blocked, try this. I've been working on a translation, but felt it was too depressing to post. Maybe it's time:

Don't Ever Be a Chinese Child

Don't be a child of Karamay

whose burns would scorch a mother's heart

Don't be a child of Salan Town

who finds no rest beneath dark waters

Don't be a child of Chengdu

who waits for mum's return

after her week-long binge

Chorus (children laughing)

Don't be a child of Henan

where AIDS cackles in the blood

Don't be a child of Shanxi

where mines turn dads

into baskets of coal

Chorus (laughter)

Don't be a child of Karamay

Don't be a child of Salan Town

Don't be a child of Chengdu

Don't be a child of Henan...

Don't ever be a Chinese child,

or the grown-ups will

eat you when they starve

At least in the wild,

mountain goats are fierce

enough to protect their kids

Don't ever be a Chinese child,

because mommy and

daddy are cowards

When the theatre caught fire,

they steeled their hearts

and let the cadres exit first.

不要做中國人的孩子

周云蓬

不要做克拉瑪依的孩子,

火燒痛皮膚讓親娘心焦

不要做沙蘭鎮的孩子,

水底下漆黑他睡不著

不要做成都人的孩子,

吸毒的媽媽七天七夜不回家

不要做河南人的孩子,

愛滋病在血液裡哈哈的笑

不要做山西人的孩子,

爸爸變成了一筐煤,

你別再想見到他

不要做中國人的孩子,

餓極了他們會把你吃掉

還不如曠野中的老山羊,

為保護小羊而目露兇光

不要做中國人的孩子,

爸爸媽媽都是些怯懦的人

為證明他們的鐵石心腸,

死到臨頭讓領導先走

Zhou Yunpeng is a blind folk musician - singer, songwriter and guitarist - now living in Beijing.

By Cindy M. Carter, March 19, '09

Shanghai-based blogger chinaSMACK has compiled a bilingual glossary of Chinese Internet/blogging/BBS terms. Useful for beginning/intermediate students of Chinese and Luddite old China hands alike, the glossary entries include the Chinese character(s) being discussed, tonal notation and well-written English explanations. Particulary fascinating are the entries explaining how Internet-based cultural memes morph over time (see the entries on 很傻,很天真 and 很黄,很暴力, for example). Thanks to Danwei for the link that led me to the chinaSMACK site.

By Cindy M. Carter, February 27, '09

An excellent podcast features Bill Marx of Public Radio International/PRI World Books interviewing John Donatich, director of Yale University Press. Topics include the Margellos World Republic of Letters, a newly-endowed fund to support the translation of foreign literature into English (C-E translators, take note!), the dearth of book coverage in mainstream western media and the role of university presses in publishing and promoting translated literature.

By Cindy M. Carter, September 20, '08

Here's a video from XTX and Cold-Blooded Animal, a band I consider - hands and other extremities down - the finest live rock act in China today, perhaps even the whole of Asia.

Although they have toured in Europe, the U.S. and Japan, they sing only in Chinese and record no western cover songs. When asked why he doesn't record western covers, lead singer XTX had this to say: "I'll start singing covers [the day] I run out of other things to say."

The band (see Wiki website) has been a fixture of the Beijing rock scene for twelve years, has released three albums and has sold hundreds of thousands of official copies, and perhaps millions of pirated copies.

The song here is titled "Grandfather". Don't know if it is a coincidence that XTX is wearing a t-shirt depicting Chairman Mao, the grandaddy image of them all.

By Cindy M. Carter, August 18, '08

Well worth a look is Joel Martinsen's August 14th post on Danwei.org ("How the Nazis brought about the end of the Cultural Revolution"), which examines the political and historical background to Chinese translations of works by Trotsky, William L. Shirer (The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich) and others.

The post includes a full translation of Luo Xuehui's article in China Newsweek. Here is an excerpt from Joel's preface:

The translations belonged to a category known as "grey books" (灰皮书), translations of foreign political and sociological texts not intended for public circulation. Limited-circulation translations of foreign literary works were known as "yellow books" (黄皮书). In the early 1960s, when China was engaged in an ideological battle with the Soviet Union, its party leadership needed to read "revisionist" works in order to understand and combat the arguments of the opposition.

The books and their translators were addressed by two Chinese newsweeklies this summer. In a lengthy New Century Weekly feature on the genesis and influence of yellow and grey books, Zheng Yifan explained how the "grey book" project grew out of a mission to translate the works of Trotsky into Chinese...

Read the full post on Danwei.

By Cindy M. Carter, August 9, '08

On August 7th 2008, The PEN American Center held an event in New York City in support of over 40 Chinese writers and journalists who have been detained, imprisoned, harassed or prevented from publishing their writings in China. See the PEN American website for more information about the featured authors and readings (includes audio recordings, Chinese and English texts and photos).

Although this was not included in the readings, I’d like to add this couplet by Li Rui (former secretary to Mao Zedong) written during his eight years in Beijing’s Qincheng Prison:

How does a life in letters make a prison?

I’ve surpassed my own self-criticism.