Our News, Your News

By Nicky Harman, January 1, '10

- Five Spice Street

By Can Xue

Translated by Karen Gernant and Chen Zeping

Yale University Press, 2009

- Banished

By Han Dong

Translated by Nicky Harman

University of Hawaii Press, 2009

Reviewed by Aamer Hussein, Pakistani short story writer and critic

More…

Throughout the second half of the 20th century, Chinese literature developed in isolation, with its own traditions and narratives. Living in a communist bubble, writers had to toe the party line, embracing socialist realism and revolutionary romanticism. They didn't begin to experiment with style and form until foreign works began to appear in translation after the Cultural Revolution. In the past 10 years, some Chinese novels, often featuring stories about the dark corners of Chinese society—such as the sex-and-drug chronicles Shanghai Baby by Wei Hui and Mian Mian's Candy—have achieved international recognition, but by and large, contemporary Chinese literature remains unknown outside the country.

“He wrote the documents and used the Internet to publish them in order to slander and urge other people to overthrow our country’s democratic dictatorship and our socialist system,” the verdict said. “…The published documents have been spread through links and republishing. People read them and they have a bad effect. This is the crime of a major criminal and should be severely punished according to the law.”

4 January 2010 is the 70th birthday of Gao Xingjian, the 2000 Nobel Laureate in Literature. To celebrate his birthday, a symposium will be held at SOAS, University of London, featuring a lecture by the author and the screening of three of his films. Mr Gao Xingjian is both a writer and a painter. The symposium will focus on his works and thoughts, and his contribution to fiction, poetry, drama and theatrical art, Chinese ink-painting and film, as well as his theory of art and literature.

By Cindy M. Carter, December 30, '09

According to the 2009 translation database compiled by the literary website Three Percent, there were 348 new translations of fiction and poetry (283 novels and short-story collections; 65 volumes of poetry) on American bookshelves this year. Of the 348 works of literature to reach America from distant shores, only 10 were penned by Chinese authors. One, Dai Sijie's Once on a Moonless Night, was translated from the French. Another - In Such Hard Times: The Poetry of Wei Ying-wu - is a collection of poetry written during the Tang Dynasty. Yang Xianhui's Woman From Shanghai: Tales of Survival from a Chinese Labor Camp, although well worth reading, is a collection of eyewitness accounts presented as fiction (or semi-fictionalized) in order to elude Chinese censors. That leaves us with a total of 7 contemporary Chinese novels translated into English for the American literary marketplace in 2009. Seven. Books. From China. To America.

Compare this to the stats for other translations from various languages published in the U.S. this year: 59 from Spanish, 51 from French, 31 from German, 22 from Arabic (a mark of progress), 18 from Italian, 18 from Japanese, etcetera.

Here's the link to the Three Percent translation databases for 2009 and 2010. And a nice little pie-chart from The Faster Times ("What Are We Translating From?") illustrating the languages from which the 348 books were translated. Chinese works form a minuscule slice of an embarrassingly tiny pie.

Since there were so few Chinese offerings published in the U.S. this year, I can easily list them all here:

-

Banished! by Han Dong, translated by Nicky Harman. University of Hawaii Press.

-

Brothers by Yu Hua, translated by Eileen Chow and Carlos Rojas. Pantheon.

-

English by Wang Gang, translated by Martin Merz and Jane Weizhen Pan. Viking.

-

Five Spice Street by Can Xue, translated by Karen Gernant and Chen Zeping. Yale University Press.

-

Feathered Serpent by Xu Xiaobin, translated by John Howard-Gibbon and Joanne Wang. Atria.

-

In Such Hard Times: The Poetry of Wei Ying-wu, translated by Red Pine. Copper Canyon Press.

-

The Moon Opera by Bi Feiyu, translated by Howard Goldblatt and Sylvia Li-chun Lin. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

-

Once on a Moonless Night, by Dai Sijie, translated from the French by Adriana Hunter. Knopf.

-

There's Nothing I Can Do When I Think of You Late at Night, by Cao Naiqian, translated by John Balcom. Columbia University Press.

-

Woman From Shanghai: Tales of Survival from a Chinese Labor Camp by Yang Xianhui, translated by Huang Wen. Pantheon.

By Eric Abrahamsen, December 26, '09

Last week, a friend called me up and told me to show up at such-and-such a place, at such-and-such a time, and to have my nice pants on. It had something to do with the Banyan Tree, one of China's oldest literary websites, but beyond that I frankly didn't catch the drift.

So this morning I went, and here's the deal: The Shanda Company, an online literature/media company which is eating up everything in sight, recently bought the Banyan Tree (榕树下, róngshùxià). The Banyan Tree was started in 1997, early days for the Chinese internet, and in the late nineties and early oughts it was the place to go for Chinese literature online. It's been pretty quiet for the past five years, but as part of Shanda's campaign to own mostly everything (someone offhandedly mentioned purchasing Paper Republic over lunch, good lord), they bought the Banyan Tree and are bringing it back to life. It was a large and loud event, attended by dignitaries such as Wang Meng, Ai Weiwei, Hong Ying, Feng Tang, Xu Xing, Lu Jinbo and a host of other half-writer, half-journalist chimeras.

As it turns out the friend who called me, whom I've always known as a highly-intelligent, deeply cynical journalist and inveterate rager against many machines, is the new head editor of the Banyan Tree. As soon as I've figured what the hell he's up to I will post in more detail, but I wanted to get this up here now, because when you go look at the Banyan Tree website (http://www.rongshuxia.com/) there's just a great big countdown clock to midnight tonight (Beijing time), at which point presumably something magical will happen. So here's this for now, watch the clock, and we'll get you something a little meatier when the fireworks are over.

EDIT: Well it wasn't immediately magical; it looks like most other online literary sites. We're on vacation at the moment, and will have a talk with the editors when we get back in early January. More then!

“There’s a set of readers out there that’s very interested in translations and international literature and is not getting what it wants,” said Chad W. Post, Open Letter’s director. “So we believe our business model can work. American literature has a lot of great works. But English-speaking readers don’t have full access to voices and viewpoints from around the world, and we’re trying to rectify that.”

We are all familiar with personal accounts of the Holocaust and the Gulag, less so with descriptions of the torture chamber that was Mao’s China. That is why Er Tai Gao’s spare, stoical remembrance, “In Search of My Homeland: A Memoir of a Chinese Labor Camp,” is a valuable contribution to the literature of the horrific 20th century.

The Financial Times reports that Mian Mian is suing Google China:

Mian Mian, a 39-year-old author from Shanghai whose realistic descriptions of life with drugs and among prostitutes, gangsters and failed artists, has attracted a large following of young readers, is suing Google for alleged copyright infringement. Sun Jingwei, her lawyer, told the Financial Times that the Haidian People’s Court in Beijing would start hearings on December 29.

Mian Mian filed her complaint on October 23. The author demands that Google apologises for scanning part of her works, deletes the scanned content from its digital library and pays her Rmb60,000 ($8,800) in compensation...

More links:

New York Times: Chinese Writer Sues Google China

China Daily: Writer Sues Google for Copyright Infringement

The international publisher Penguin Books is looking to hire an editor to work on a new list of books on and from China.

We aim to secure 5-10 original works per year, written in both English and Chinese, for international publication. The Editor role will be a broad one: he or she will work on every stage of the publishing process, from identification and acquisition of new works, MS edits, and commissions of translators through to PR, marketing, and managing translation rights.

By Cindy M. Carter, December 15, '09

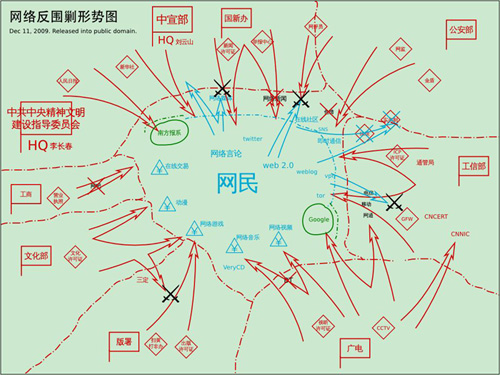

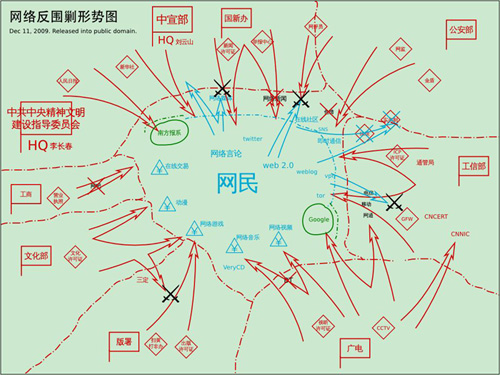

Chinese blogs, social networking sites and bulletin boards are buzzing about a humorous map of China's "Internet topography" that illustrates how China's netizens (网民, wangmin) are currently under attack from all sides. The title of the map (clever cartographer unknown) reads 网络反围剿形势图, which translates roughly as "A topographical map of resistance to [the campaign of] Internet encirclement and annihilation". Sounds clunky, I know, but it's a riff on a 1930's campaign by Chiang Kaishek and the Nationalists to encircle and wipe out communist base camps (see Wiki entry for more about the encirclement campaigns).

(Here's a larger version of the map.)

Sorry I don't have the Photoshop chops to annotate this map in English, but here are the salient details:

(1) In the center, we see China's netizens (网民) and their territory, indicated in blue. Strongholds include Google, Tor, VPN, weblogs, Web 2.0, Twitter, online speech, social networking, online music, online games, etc.

(2) On the periphery, in red, we see the territory held by various Chinese government bureaus and ministries. Red arrows indicate official encroachments; crossed swords represent recent battlegrounds; blue arrows show where China's Internet users have managed to strike back effectively.

(3) The top left is occupied by the HQ of the Spiritual Civilization Development Steering Commission (中共中央精神文明建设指导委员会), the Propaganda Department (中宣部, or 中共中央宣传部) and the State Council Information Office, SCIO (国新办, or 国务院新闻办公室), all of which are under the control of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCCPC).

Moving clockwise, we pass through the fiefdoms of the Ministry of Public Security (公安部); the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (工信部, or 工业和信息化部); SARFT, the State Administration of Radio, Film and Television(广电, or 国家广播电影电视总局); GAPP, the General Administration for Press and Publications (版署, or 新闻出版总署); MOC, the Ministry of Culture (文化部) and SAIC, the State Administration for Industry and Commerce (工商, or 工商行政管理总局). Note the red arrows coming from all directions, targeting the small blue corps.

(4) Bureaucratic turf wars: the pair of crossed swords at bottom left shows where the Ministry of Culture and GAPP have clashed over jurisdiction. The red arrows emanating from bottom right illustrate SARFT encroachments into Ministry of Industry and Infotech territory.

Somebody should make a t-shirt of this.

Eveline Chao is the author of Niubi — The real Chinese you were never taught in school. In this video, she teaches Danwei's Jeremy Goldkorn the origin of 'niubi', how to say 'fisting' and other useful phrases in Chinese. Also on Youtube.

By Canaan Morse, December 11, '09

Wednesday’s talk was given under a specific heading, the “Public Intellectual Series Number 1,” and therefore carried a mandate as well as a topic. I won’t say more to that standard beyond that its mandate was fulfilled by a clear, cohesive and relatively comprehensive lecture. Take “lecture” for its older meaning: that form of academic art that distinguishes the professors you remember from the ones you don't.

Before the talk started, Nick distributed to the audience a packet of twelve literary excerpts composed of Chinese poetry, English translations and Chinese-inspired original English poems. The list (copied directly):

Axe Handles, by Gary Snyder

Preface to Wen Fu, by Lu Ji, trans. Achilles Fang

Hearing a Bell in the Mountain Night, Chinese original (Zhang Shuo) and Nick’s translation

Nowhere to Go, Gone by Nick Admussen

Nine Quatrains of Casual Interests (the seventh), by Du Fu, Nick’s translation

In a Station of the Metro, Ezra Pound

DEATH BY WATER, from The Wasteland, by T.S. Eliot

Drip from the Eaves, by Xia Jing, trans. Silvia Marijnissen

Allusion, by Nick Admussen

Tu Fu Watches the Spring Festival Across Serpentine Lake, by Frank Bidart

Ballad of Lovely Women, by Du Fu, trans. David Hawkes (!)

I Had Come to the Four-Doored Room, by Nick Admussen

More…

The Top Ten run-down for Nov 23-29: Banned mortgage slave saga...Stephanie Meyer mania...Lijiang romance lite...Tibetan epic ballad minus the verse...

The latest entry in Canongate’s Myth Series, King Gesar, has been launched in China (格萨尔王), and the firm has confirmed that it intends to publish it in English within 2011. When King Gesar makes its appearance, it will join other creatively re-told tales commissioned by the UK publisher, including The Penelopiad (Margaret Atwood’s take on Penelope of The Odyssey), Baba Yaga Laid an Egg (Baba Yaga as per Dubravka Ugresic), and Binu and the Great Wall (by China’s Su Tong).

Check out the book review and learn about the "integrated marketing campaign" now underway...

By Canaan Morse, December 8, '09

What: Bookworm Public Intellectual Series 1: Nick Admussen

Where: The Bookworm, Sanlitunr Nanjie

When: Dec. 09, 7:30-9:30 p.m.

Nick Admussen is a PhD candidate in Chinese literature at Princeton University, and is also a published poet and translator. He will be talking about the influence of Chinese poetry on poetry elsewhere in the world, and of the difficulties facing literary translators.

See the Bookworm posting for more.

More…

By Eric Abrahamsen, December 8, '09

The Foreign Correspondent's Club of China held an event last Friday that was a sort of retrospective on the Frankfurt Book Fair – lessons learned, insights gained, etc. (details here) The four speakers were Michael Kahn-Ackermann, head of the Goethe-Institute in Beijing; Jo Lusby, General Manager (China) of the Penguin Group; Zhou Wenhan, a freelance writer based in Beijing; and Kristin Kupfer, a German freelance journalist.

The discussion, held in the Sequoia Cafe, was good – highlights (from my point of view) included Michael Kahn-Ackermann's point about the enormous disconnect between the official delegation and the Chinese writers who attended. Essentially that the two groups had entirely separate goals, different methods of presenting themselves, and different styles of communication. Jo Lusby continued this with comments that the government would have to learn how to balance its control over "the message" with allowing those people who actually create culture to do their work. There was also a lively debate/argument over the responsibilities of the western press, with one excitable audience member (a journalist) saying, "When we ask Mo Yan if he's a dissident writer he has to answer!"

Zhou Wenhan, the freelance journalist, wrote his remarks out in Chinese, which were then ably translated and read by Jonathan Rechtman. I was impressed with how succinctly and forcefully he presented some very important ideas about how the Chinese government works, and so rather than regale you with half-remembered anecdotes I will paste below, with permission of both author and translator, the English version of what he said:

Kristin has asked me to talk about the strategic issues surrounding the communication between the German and Chinese organizers in a broader sense, but I'm not part of any government think tank or anything, so I can't really say much about the strategic side of things. I can only speak about some of my observations as to how the Chinese government seeks to manage information in all of its interactions with other countries, whether in terms of cultural exchanges, international conferences, or the Olympics.

More…

By Canaan Morse, December 2, '09

Title: *IUP Alumni Event: An Evening with Hong Ying

When: Sat Dec 05 17:30:00 +0800 2009

Where: Yuanfen New Media Art Space, 798

Description: IUP alumni, teachers, and students are cordially invited to join us for an evening program of literature, music and Sichuan food courtesy of 天下盐. Critically acclaimed author 虹影 will read from and talk about her newest work, Good Children of the Flowers. Musical interludes from cello and viola duo Kevin Olusola and Wu Tsong.

Please RSVP to David Chao

(e: david.chao@alumni.jesus.ox.ac.uk, t: 152 1013 4389)

IUP Alumni and Guests: RMB 200

Current IUP students and teachers attend free of charge.

Tickets may be purchased at the door

More…

This time, it came in through the wall, emerging like a spirit from an oil painting of a revelry of the Greek gods. It was about the size of a basketball and shone with a hazy red glow. It drifted gracefully over our heads, leaving behind a tail that gave off a dark red light. Its flight path was erratic, and its tail described a confusingly complicated figure above us. As it floated, it whistled a deep tone pierced with a sharp high whine, calling to mind a spirit blowing a flute in some ancient wasteland.

By Cindy M. Carter, December 2, '09

I have to admit: I've often dismissed (and sometimes dissed) the generation of Chinese writers born in the 1980s. There were so many prodigies, kids who started publishing not long after they became pubescent. Clearly, there was some precocious talent, but by the second or third book, you had to wonder if these teenage authors had experienced enough of life to be able to write about it.

I'm not asking that question anymore. The kids have come of age. They're in their mid- to late-twenties now, they've got a different attitude than their predecessors, they're blogging, and they're definitely writing some things worth reading.

I've been following the post-80's writers for a while now, and am finally seeing some things that knock my socks off.

Here are some short bits from two authors, both born in 1982. Zhang Yueran has been writing since she was 14; Han Han published his first novel when he was 17. Both are among China's most popular writers, and have sold millions (probably closer to tens of millions) of books between them.

Han Han, in response to how he feels about being a "public intellectual":

"Being a public intellectual is a lot like being a public toilet. Anyone can stop by and take a piss for free, and they don't have to clean up afterward. If you try to charge them 50 cents for toilet paper, they'll bitch about it and start kicking at your walls. But a city's got to have public toilets, otherwise people just crap in the streets. It's a pretty pathetic role sometimes, but if everyone in the city, even those who have their own bathrooms at home, comes to take a dump in the public toilet, well then... maybe there's some hope for this society yet."

Zhang Yueran, in her recent short story "Gone Astray":

"I could tell right away that Lin was a kindred spirit. Meeting him made me realize that two 'kindred spirits' need not necessarily like each other. I wasn't even sure if I'd want him as a friend, but I had to admit we had a lot in common. Lin was older than I'd expected, forty at least, small and rather scrawny. But he didn't seem to have been born that way: it was more like a lifetime of disappointment had whittled him down to size."

By Cindy M. Carter, December 1, '09

Maybe it's a meaningless list based on dubious statistics, but it's still fun. There are the usual popular authors, with a strong showing from writers of children's books and young adult literature. Nice to see some very worthy and serious authors on the list this year: Wang Meng, Yan Lianke and Alai, among others. To paraphrase Deng Xiaoping, 让部分作家先富起来 ("Let some of the writers become wealthy first.")

The highest-paid authors in China, 2009 edition