Our News, Your News

By Nicky Harman, May 24, '17

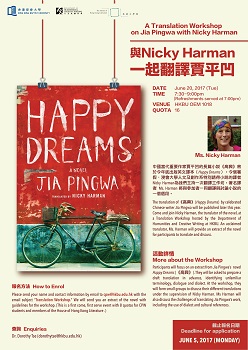

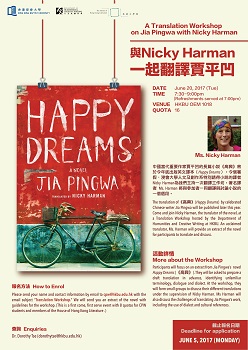

I'm running a translation workshop at Baptist University in Hong Kong on Tuesday 20th June 2017. We'll be working on a short piece of text from Jia Pingwa's novel 《高兴》. The event is free but please register by Monday 5th June to receive the text. Contact: cpw@hkbu.edu.hk and put Translation Workshop in the subject line.

Chinese Journeys: a special issue on new Chinese writing featuring poetry, prose, translations and commentary

Cover image by Ruihua Zhang

"如何成为一只闪闪发光的猪” 的王小波主题沙龙 (摘选):

“ 在王小波作品当中看到的性,并没有任何饥渴,他的性是潇洒、温柔的性,他没有把这个事当作禁忌、当作偷窥的乐趣、让读者有感官的刺激,而是把性当做吃饭、谈恋爱、调情一样的正常的事情去写。所以他作品里的性不猥琐,甚至被唤起的感官反应很少,因为他把性日常化。这是在中国作家,尤其上世纪九十年代的中国作家中非常少有的。”

By Bruce Humes, May 20, '17

Buruma knows Chinese and often writes about topics related to China and Japan. See news of the announcement here.

By Bruce Humes, May 19, '17

France’s Macron has named a woman, Françoise Nyssen, to fill the position of Minister of Culture. She has served as CEO of Éditions Actes Sud, which has published French translations of works by writers such as Bi Feiyu, Chi Li, Ma Jian, Mo Yan, Li Ang, Wang Xiaobo, Wuhe, Yu Hua, Zhang Xinxin and Zhaxi Dawa.

The expansion of Qidian International will provide China Reading and its writers with a platform to reach readers globally and the potential to become one of the largest platforms globally in online reading. Qidian International's key target markets include North America, Western Europe and Southeast Asia with future potential expansion into Eastern Europe. The content on Qidian International will primarily be in English with future potential editions in Thai, Korean, Japanese, and Vietnamese provided through cooperation with local-language internet platforms. In addition to the Qidian International website, the Qidian App, available on both Android and iOS are expected to be frequently updated for content and functionality.

As 一带一路 takes off, there will be opportunities for translation of Chinese writing into several languages, including English, and those of Central Asia and East Africa.

If you don't know about "Belt & Road," just watch . . .

The plan points out that the CWA should stick to cultural self-confidence. It calls for writers to closely unite around the CPC Central Committee in a bid to enrich and develop the literature cause of socialism with Chinese characteristics.

For nearly six decades, Mr. Watson was a one-man translation factory, producing indispensable English versions of Chinese and Japanese literary, historical and philosophical texts, dozens of them still in print. Generations of students and teachers relied on collections like “Early Chinese Literature” (1962), “Chinese Lyricism: Shih Poetry From the Second to the Twelfth Century” (1971), “From the Country of Eight Islands: An Anthology of Japanese Poetry” (1981) and “The Columbia Book of Chinese Poetry: From Early Times to the 13th Century” (1984).

Author Yan Lianke on the death of translator Sylvie Gentil:

她是翻译家;是极好极好的翻译家。她对中国文学的爱,胜过许多中国作家对中国文学的爱;对中国作家的爱,也胜过我们自己对自己的爱。法国人,却有近20年的时光都住在北京工体的周边上,就像一个中国人,半生都在国外默默地蛰居和生活,读书、写作和翻译。把阅读、翻译中国当代作家的作品当成自己的吃饭和穿衣。

莫言、徐星、李洱、冯唐、杨继绳和我等,许多中国作家走进法国是通过她才打开了巴黎文学场上的那扇门。《红高粱》、《无主题变奏》、《花腔》、《万物生长》和《墓碑》,那些在中国或响亮、或沉寂的虚构或者非虚构,由她的心血浸润、翻译后,才在世界文学在法国那最为巨大、热情的卖场上,有了中国作家的响动和一丝丝的光。

“You’re making a living as a writer now, so put everything you have into it. When it comes time to winnow, the farmer takes advantage of every gust of wind. Take advantage of the time alone to work as hard as you can. But I have heard that you have been drinking a lot. When you were young I didn’t provide a positive example for you to follow. I’ve now stopped drinking completely.” When I read the letter, I was deeply ashamed and swore off liquor altogether. I finally sent a letter back to my father, entreating him again to live with me in the city, along with my daughter.

Candied Plums is a US-registered publisher, selecting Chinese picture books of high quality and publishing them in English in the US - some books are published solely in English, some are bilingual editions. The first season of books is available now - through the usual online bookshops - and there's a pdf catalogue on their website. The website is great - and includes info about the books, the authors and translators. There's also a section called Chinese Corner, complete with audio (listen online or download) so you can read along too.

Le début des années 2010 marque sa maturité d’écrivain. Il revient vers l’écriture en chinois, mais, comme l’a dit Ou Ning (欧宁) qui l’a découvert à ce moment-là, lors d’un voyage à Hotan dans le cadre du projet du peintre Liu Xiaodong (刘小东) sur les mineurs de jade locaux: « Le chinois n’est pas sa langue maternelle, ses récits en chinois n’auront donc jamais une texture raffinée, mais c’est justement ce qui les rend si attrayants… Il intègre dans son chinois la manière de penser ouïgoure, si bien que son écriture a une fraîcheur unique ; sa narration pleine d’humour et de poésie donne au lecteur une nouvelle expérience de lecture, différente des récits chinois …».

"Given the sobering history of representing disabilities in Chinese children’s materials, The King of Hide-and-Seek, a picture book published in 2008, is a refreshing take on the topic." - review by Minjie Chen

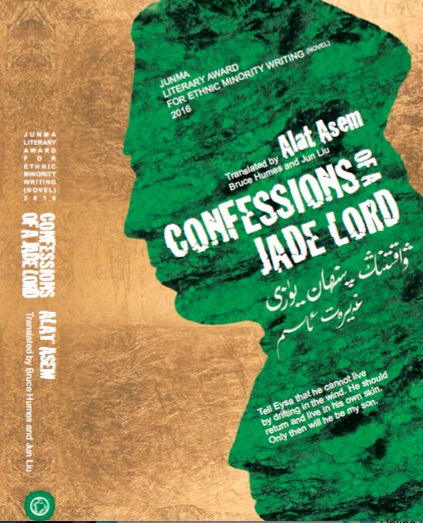

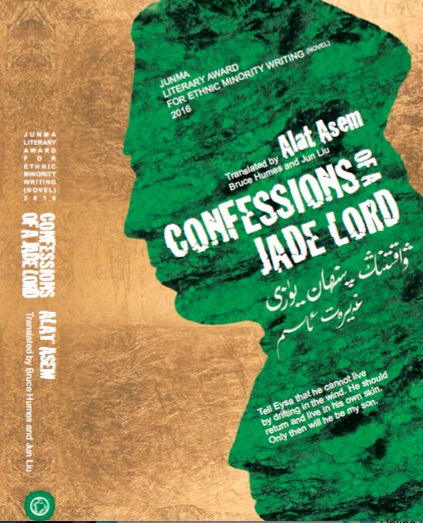

Alat Asem's fiction is a Uyghur world set in Xinjiang where Han just don’t figure; his hallmarks are womanizers, insulting monikers and a hybrid Chinese with an odd but appealing Turkic flavor . . .

The novel is an indictment of ‘mythorealism’ — strikingly similar to today’s concept of ‘fake news’

Is a translator effectively the co-author of a text and if so should he or she be paid a royalty as authors are?

Candied Plums draws on a stable of esteemed translators—many affiliated with Paper Republic, the network for Chinese translators—including Helen Wang, who recently translated Cao Wenxuan’s Bronze and Sunflower (Candlewick, Mar. 2017). “We definitely have talented editors who know how to translate just the right way: to preserve the integrity of the original text but also to reach out to people who are not necessarily familiar with Chinese politics or culture,” Feldman said. She pushed for Candied Plums to feature translators’ names prominently on all book covers, saying: “They are co-authors.”

By Nicky Harman, March 27, '17

Literary Translation in Practice 26th - 30th June 2017, City University London

Are you a practising professional or a newcomer to the art of translation?

Develop your translation skills under the guidance of top professionals at a central London campus.

An immersion course in literary translation into English across genres - including selections from fiction. poetry, history, essays, journalism, travel and academic writing - taught by leading literary translators and senior academics, with plenty of opportunities for networking.

• Arabic - Ruth Ahmedzai Kemp

• Chinese - Nicky Harman

• French - Trista Selous and Frank Wynne

• German - Shaun Whiteside

• Italian - Howard Curtis

•Japanese-Angus Turvill

• Polish - Antonia Lloyd-Jones

• Portuguese - Daniel Hahn

• Russian - Robert Chandler

• Spanish - Peter Bush

• Swedish - Kevin Halliwell

Evening programme (attendance free): French Translation Slam with Frank Wynne and Ros Schwartz; Keynote Lecture Who Dares Wins by Professor Gabriel Josipovici; Author/translator Daniel Hahn on Translation and Children's Books and a buffet supper at local gastro pub sponsored by Europe House with a talk by Paul Kaye, Europe House Languages Officer.

Full fee: £520. Bursaries available.

Directors Amanda Hopkinson (Visiting Professor in Literary Translation. City, University of London) and French literary translator Ros Schwartz

Please note: All translation is into English and English needs to be your language of habitual use. All evening and lunchtime events are free and attendance is voluntary.

The organisers reserve the right to cancel a workshop that does not recruit to the required minimum number of participants. Any applicants for these groups will be notified with a minimum six weeks' notice.

在今年年初一篇回顾自己耗时十七年翻译《西游记》过程的自述中,林小发写道,她在翻译过程中尽量读了一些构成明代文人常识的经典,包括四书五经、佛经,还有与《西游记》相关的一些道教经典,如此一边阅读一边调查研究,“翻译过程也就成为了一个独特的‘取真经’的过程。”

RRobert Silvers died on Monday, March 20, after serving as The New York Review of Books Editor since 1963. Over almost six decades, Silvers cultivated one of the most interesting, reflective, and lustrous stables of China writers in the world, some of whom offer their remembrances below.

British students may soon study mathematics with Chinese textbooks after a “historic” deal between HarperCollins and a Shanghai publishing house in which books will be translated for use in UK schools.

China’s wealthy cities, including Shanghai and Beijing, produce some of the world’s top-performing maths pupils, while British students rank far behind their counterparts in Asia.

"We have the parallel running of the two stories of Mulan and the modern girl; and the surprise ending which highlights the different perception of gender between Mulan and the modern girl. Qin Wenjun asked me to say that she has written more than 10 picture books, and that this book is the most courageous, challenging, demanding and, in a sense, the happiest one."

. . . and The Dream of the Red Chamber proves it!

Anna Gustafsson Chen reviews Peng Xuejun’s 彭学军 award-winning novel Sister 《你是我的妹》 ... "a beautiful and dramatic story for older children that takes place in Yunnan, sometime in the early 1970s"

"One feature the GLLI site offers now is a Blog page which has a monthly focus on a language and its literature issues in translation. February just focused on Chinese, for example. This month will focus on French literature." Thanks again to everyone who contributed to the Chinese month!

By Helen Wang, February 28, '17

This is the last day in February, and our last post in the Global Literature in Libraries - Paper Republic series on Chinese literature. Thank you for following us! We're very grateful to all our contributors - we couldn't have managed a post a day without you! So far, all our contributors have a strong Chinese connection. But Chinese literature is not just for Chinese readers - so we asked Marinella Mezzanotte, a London-based writer (in English) and a translator (from Italian to English), who is a newbie to Chinese literature to tell us about one of our events and whether it worked for her. In December 2016 she came along to our second speed bookclub event organised by Paper Republic and the Free Word Centre in London. Here's Marinella's response:

More…

By Helen Wang, February 27, '17

Our penultimate post is about popular Chinese fiction of the ghostly, grave-robbing kind. We are thrilled to post this piece by writer and translator Xueting Christine Ni, who is currently working with the fantasy and science fiction author Tang Fei, and writing a book on Chinese deities. Having studied English literature in London, and Chinese literature in Beijing, she is now based mainly in the UK.

More…

By Helen Wang, February 26, '17

Chun Zhang is the translator of a beautiful children’s book The Story of Ink and Water by Liang Peilong and Li Qingye. We are always on the look-out for great children’s books created by Chinese writers and illustrators, and this one is due for publication in March 2017. We invited Chun to tell us more about it...

More…

By Helen Wang, February 25, '17

Theresa Munford teaches Chinese at a secondary school in the UK. She took the initiative a few years ago to set up a Chinese book group. At a workshop on Chinese children’s literature in 2016 she played a video in which she interviewed two of her teenage students about the Chinese books they had read. They spoke frankly and eloquently about the books they had read. We invited Theresa to tell us more about the bookclub...

More…

By Helen Wang, February 24, '17

In October 2015 the Chinese government announced major changes to their population policy, commonly known as the One Child policy. Instead of curbs that limited one-third of Chinese households to strictly one child, Chinese families across the nation could have two children starting from 1 Jan 2016. With incredible timing, Pulitzer Prize winning journalist Mei Fong's book One Child was at the publishers! I was invited to review it for the Los Angeles Review of Books and found Mei Fong's book very readable - there was a perfect balance of detailed research and stories of individual people in real circumstances. I particularly appreciated Mei Fong's skilful vignettes - for example, the couple in Wenchuan, who, within days of losing their teenage daughter in the devastating earthquake, decide to try for another child. The odds are stacked against them (age, vasectomy, cost, friends and family avoiding them for fear of being asked for money or support) and you wonder if they are grasping desperately at straws. Yet Mei Fong slips their shoes on to your feet so softly that you find yourself wondering how you would respond in their situation.

More…

Call for Papers - by March 7, 2017

A Roundtable sponsored by the LLC Modern and Contemporary Chinese Forum for the MLA Annual Meeting in New York, Jan. 4-7, 2018.

By Helen Wang, February 23, '17

Spring 2017 will see the publication of The Ventriloquist’s Daughter, by Lin Man-chiu (tr. Helen Wang), the fourth Young Adult novel translated from Chinese and published by Balestier Press. Originally from Taiwan, Lin Man-chiu has travelled extensively in South America, and her experiences there inspired this story. The following piece is adapted from the Author’s Preface in the Chinese edition, and we’re delighted to have permission to publish it here.

More…