The Cosmopolitan, the Quotidian, and the Anthropocene Turn in Sun Dong’s 2020 Pandemic Poetry

“春天在人类纪

欲呼无气,欲加口罩”— 孙冬《注视》

“Spring in the Anthropocene

You who’d scream to breathe, add a mask”— Sun Dong, “Fixed Gaze”

空山不見人, 但聞人語響。

— 王維《鹿柴》

Empty mountains:

no one to be seen.

Yet — hear — human

sounds and echoes.— Gary Snyder’s translation of Wang Wei’s “Lù Zhái”

“I’ll be back, I'll re-emerge, defeated, from the valley; you don’t want me to go where you go, so I go where you don’t want me to. It’s only afternoon, there’s a lot ahead.”

— Frank O’Hara, “Meditations in an Emergency”

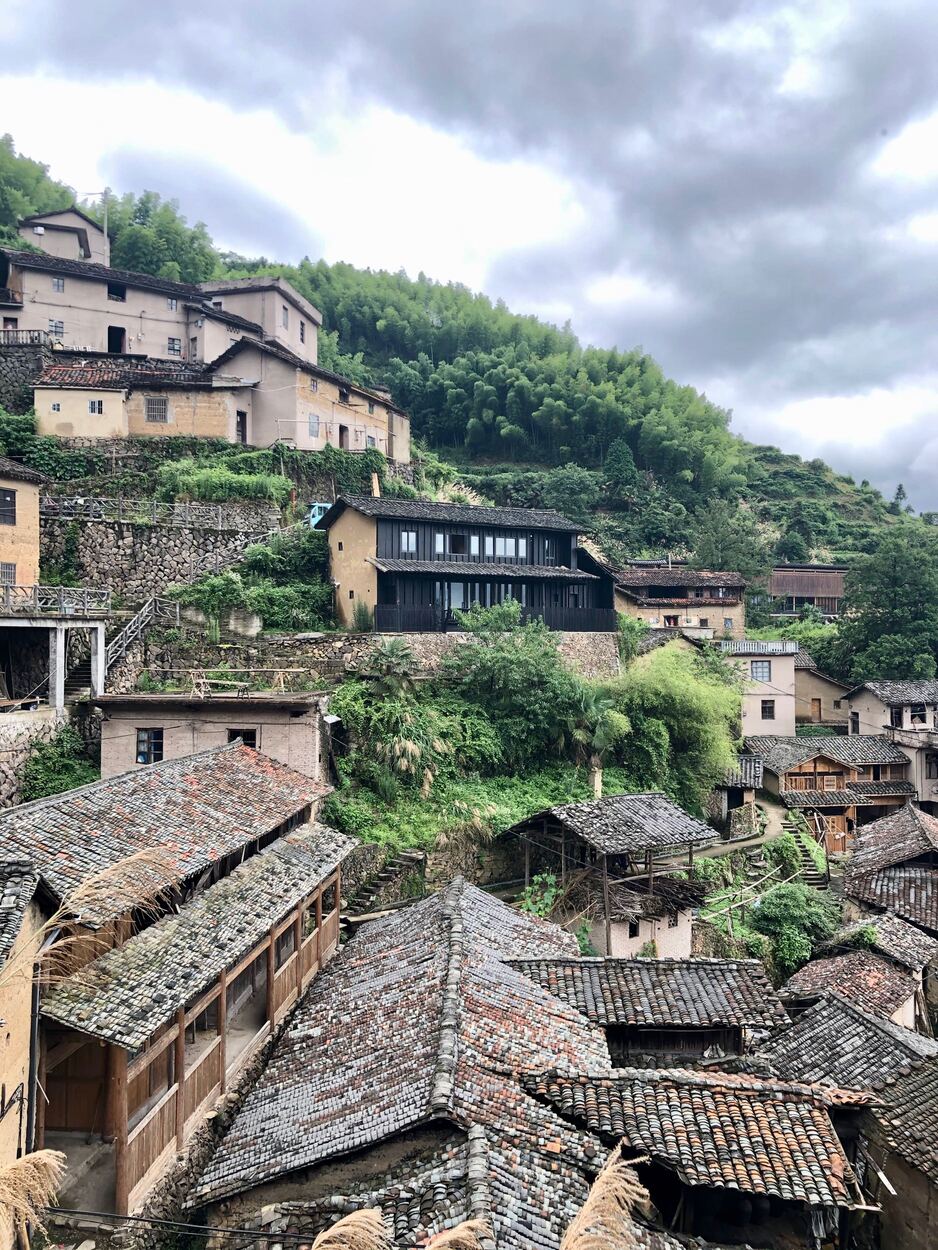

Generally, we encounter writers in two ways: through their writing and, at times, in person. (Encounters via translation add another, stranger dimension.) When I departed Shanghai via high-speed train for Lishui, where I would meet the driver who would take me up to the mountain village of Chenjiapu, I anticipated spending time both in person and on the page with the Nanjing-based poet Sun Dong. We would meet after I’d drafted translations of her new poems — all written in the first few months of 2020 — during my two-week literary translation residency in a place that has, in recent years, gone from remote “hollowed-out village” to a burgeoning writers’ colony and boutique travel destination. Chenjiapu retains its rustic charm, with longtime residents still cultivating small plots cut from a mountainside so rugged that the village is car free of necessity, even as scores of tourists amble about on any given day, whether they’re coming from the Stray Birds Art Hotel, hiking up from a B&B further down the mountain, or pouring forth from a bus parked just outside the village where the winding road to Chenjiapu ends.

I knew, too, that I’d likely encounter other Chinese writers, ancient, classical, modern and contemporary. Despite being in a village of some 500 permanent inhabitants, I would be staying in a comfortable studio in a renovated old home right across a picturesque ravine from the remarkable Chenjiapu outpost of Librairie Avant-Garde (先锋书店) which, in partnership with Paper Republic, sponsored my Chenjiapu translation residency. Their range of books is impressive and includes a fantastic poetry section, so there would be plenty of opportunities for on-the-page encounters. There was the chance, too, that I’d meet one or more of the writers who have their own studios in the area in person. And not long after my arrival I learned that poets Chen Dongdong (陈东东), Zhang Dinghao (张定浩) and Hu Sang (胡桑) would be coming to give talks and workshops (sadly, I had to return to Shanghai just before their arrival).

I hadn’t, however, expected Frank O’Hara. And I certainly hadn’t expected a Chinese-speaking O’Hara offering ghostly cold comfort in these overheated times of global pandemic and deepening ecological crisis. Yet as I began my work the day after arriving there he was, his words, in Sun Dong’s translation, aglow on my screen. Outside my window, tendrils of mist laced their way over and through the forested slopes, obscuring brick-and-clay walls and black-tiled rooftops, as well as a distant, gleaming microwave tower that delivered the admirably stable Songyang County public wifi signal to my laptop (a truly classic contemporary Chinese landscape scene). Meanwhile, from my screen O’Hara addressed our 2020 pandemic planet from late 1950s Atomic-Age Manhattan. The poem begins:

Thinking of O'Hara Mid-Epidemic

Thinking of Frank O’Hara on the Lunar New Year

I said to myselfGeological strata sink and shear into conflicting opinions, the problem an impossible knot

My shoes still aren’t broken in, one more phantom enemy

The event is yet to happen, butFrank O’Hara says

in a sense we're all winning

we're alive…

疫情中又想起奥哈拉

新年那天我想起了奥哈拉

我对自己说地质层陷入分歧, 问题打成死结

鞋没有变得舒服,假想敌又多了一个,

事件仍未发生,然而弗兰克 奥哈拉说

在某种意义上讲我们都赢了

我们还活着……

My initial surprise at finding O’Hara in Chenjiapu soon faded. It suddenly seemed natural that he would be there, his lines from his 1964 Lunch Poem “Steps” echoing in Sun Dong’s Chinese. She’s a cosmopolitan, global poet as much as she’s a Chinese poet, frequently translating her own work into English and, as a professor in Nanjing, teaching Anglophone literature and Western literary theory. I first encountered her and her work at a 2018 conference in Suzhou where she appeared with New York poet and publisher James Sherry, then again later in Shanghai when I hosted her for a reading with Pulitzer Prize-winning poet and translator Forrest Gander at NYU Shanghai. The Suzhou conference had been organized by the poet Che Qianzi, whose work1, like that of Sun Dong and many other contemporary Chinese poets, draws significantly upon modern and contemporary American writing, including the New York School, Language Poetry, and other experimental 20th century veins.

Yet a deeper surprise persisted — an uneasy one, less the delight of recognition than a doubly uncanny sense of what Sun Dong terms “the betrayal of déjà vu” (似曾相识的背叛) in her poem “Fixed Gaze” (注视). It’s the feeling of living in a 21st century “shadowtime,” which British nature writer Robert Macfarlane has defined as “the sense of living in two or more orders of temporal scale simultaneously.” It’s a problem that the historian Dipesh Chakrabarty tackles in work like his essay “Anthropocene Time,” calling for us to find ways to think and feel “human‐historical time and the time of geology” simultaneously as we irrevocably change the planet and as planetary changes (including outbreaks of diseases new and old) inevitably change us. Her work is suffused with this awareness, insisting quietly and steadily — and at times forcefully — that the reader, too, see our contemporary world as it is, not as it was or as we might wish it to be.

Since the turn of the century, when Nobel laureate chemist Paul Crutzen led the effort to popularize the idea that the planet has entered the Anthropocene — a new geological epoch in which human influence has become the primary force in driving planetary change — writers and artists have done much to forward a conversation that otherwise might remain obscure to those outside the sciences. The hallmarks of the Anthropocene are terrifying: climate disruption, mass extinction of species, acidifying oceans, saturation of soil and water with microplastics, intensifying flooding in some areas and drought in others, and so on. As I worked further into that first translation, my surprise subsided once again. Sun Dong is one of many writers globally working, to one degree or another, in an “ecopoetic” vein.

The sense of uneasy awareness remained, however — an effect, I argue, that is a mark of much of the most important and compelling contemporary writing of our time. This feeling simmered beneath the surface as I worked, arising like mist from the fissure in the poem over which the reader must awkwardly leap to get from the cosmopolitan sophistication and cultured pleasures embodied by O’Hara to a line about “geological strata” and “conflicting opinions” in the context of the coronavirus pandemic. We’re not in O’Hara’s 20th century world anymore. We’re not even in 2019’s world. We’re probably not in the Holocene Epoch any more: so goes the Anthropocene thesis. But the pasts we leave behind haunt us, as do our increasingly strange possible futures as they colonize our shaky, protean present. I began to understand something about what I find so compelling in her work: the juxtaposition of literary wit and aesthetic acuity with not only the everyday pleasures and pains of living as we do (“My shoes haven’t broken in”) but also with an awareness of the Anthropocene. In “Fixed Gaze” she explicitly names it; elsewhere, it permeates the work, contaminating with the new abnormal:

Fixed Gaze

Spring in the Anthropocene

You who’d scream to breathe, add a maskDon’t pick your nose or suck on your fingers

No getting together and no making love

Don’t start rumors and don’t spread rumors, get it?

Got it?The wind’s fixed gaze through the barely slit blinds

The webcam’s fixed gaze from the top of the screen

Shall my existence be fixed here in this instance, exist

henceforth hereafterEven more than the bedroom the kitchen resembles a classroom

Packed tight with boundless desire

Hung thick with all manner of torture implements

Smash what’s smashed,

Cut what’s cut,

Roast what’s roastedThe betrayal of déjà vu, in spring

the flowers bloom and wither, the swallows return, life thrives

in this divide-and-collide Human Epoch

whose existence shall be fixed by whose gaze

hereafter thereafter

注视

春天在人类纪

欲呼无气,欲加口罩不抠鼻子不吸吮手指

不聚集不做爱

不造谣不传谣,你明白了吗?

听懂了吗?风从百叶窗的微缝里注视

摄像头从屏幕上注视

将我存在于此,存在于

从此以后厨房比卧室更像教室

装满无限渴望

挂满各种刑具

粉碎的粉碎,

切割的切割,

烧烤地烧烤似曾相识的背叛,在春天

花开花谢,燕子归来,众生安好,

隔着人类纪

谁的注视将他们存在于此

存在于从此之后

It’s not just the eventual exhaustion of our individual persons or youthful adventures that we must contemplate, à la O’Hara in 1957’s “Meditations in an Emergency” — “[e]ach time my heart is broken it makes me feel more adventurous ... but one of these days there’ll be nothing left with which to venture forth.” And it’s not the historical tragedy of a fallen dynasty or state that is to be mourned, or even the death of a culture: it is rather life as we know it in its geologically recent abundance and variety. “Fixed Gaze,” while obviously addressing the surveillance state and its management of the coronavirus outbreak in China, is also, inescapably, rooted in — or perhaps better said to be uprooted from — the deeper ground from which the outbreak arose, as the opening couplet makes clear.

This element isn’t new to Sun Dong’s poetry, and it is, I think, the element that first drew me to her work. Since moving to Shanghai over ten years ago, I’ve become increasingly interested in how writers and artists in China are engaging not only with crises of pollution, wildlife habitat loss, and habitat fragmentation (a driver of zoomorphic virus transmission to human populations) and other obvious effects of accelerated development, but with the overarching questions of climate change and the Anthropocene. Thus, Sun Dong’s engagement with geologic time — a key component of the Anthropocene turn — resonated with me when, several years ago, I read Josh Stenberg’s translation of an earlier poem, “Wall,” which begins:

Geographic change is too slow

a species goes extinct too slowly the years roll on

everything is the opposite of the poetic

the carrot top is a little conspirator Brodsky also drank gutter oil

Again, the quotidian (“carrot top”) nestles within the awareness of larger, longer, slower processes (extinction, “geographic change”) from which mere history unrolls. It’s a blunt material account that, being the “opposite of poetic,” may constitute the most honest kind of poetry left to us. Its lineage lies in a cosmopolitan, global, literary tradition, in this case signaled by the reference to Joseph Brodsky — another poet, as it turns out, with an interest in geoscience, having worked as a geologist’s assistant in Russia prior to his emigration to the United States. Though unlike Brodsky, or Forrest Gander, who studied geology prior to becoming a poet, Sun Dong has no formal background in geosciences, she frequently references deep time — geological, “geographical,” and evolutionary timescales — in her work.

Consider, for example, from her 2020 poem “The Contemporary” (《当代》): “In this Museum / I believe in the ginkgo and cockroaches alone / these two most ancient of creatures” (这座博物馆 / 我只相信银杏和蟑螂 / 这两种最古老的生物). Likewise, from “Dog Rose and Wild Pear (《狗蔷薇和野梨》): “My dog rose has lived 40 million years already / My wild pear too is older than humankind / I tend to their lives, facing earth’s childhood, offer / a greeting, pay homage to humankind’s earliest efforts at cultivation / Pure species should not vanish”(我的狗蔷薇已经生活了4000万年 / 我的野梨也比人类更老 / 我打理它们的生活,只是向地球的童年 / 致敬,向最早驯化他们的人类致敬 / 单纯的物种不该绝迹). And though the longer poem “The Conversation” (《谈话》)seems, primarily, to be about the epistemological and ontological crises of the psyche under pressure of surveillance, the “I” of the poem, in the course of being interrogated within a “kind of homogenized dreamworld” (一种均匀的梦境), finds herself being questioned about “that chance encounter between you and that extinct bird,” to which she responds, “Of course something like that must have taken place long ago / The extinct bird is not contained by time” (你与绝迹之鸟之间的短暂邂逅 / 发生在哪一年?/ 那是很久之外的一个事件 / 绝迹之鸟,它不在时间的控制之内).

It was, in part, this side of her work that led me to invite her to read at NYU Shanghai last year with Gander, who was in China at the invitation of Shanghai poet Wang Yin for a poetry festival. Gander, author of key ecopoetics texts, such as “The Future of the Past: The Carboniferous and Ecopoetics,” is also a prolific translator. Sun Dong’s own interest in translation is central to her poetic practice — she co-edited with Sherry the experimental Reciprocal Translation Project, which invited Chinese and American poets to translate one another, and she frequently creates her own freely experimental translations into English from Chinese of her own poems. As it turns out, Gander chose to read primarily from his translations of Spanish-language poets in their joint reading, and a conversation that foregrounded translation — the sine qua non of cosmopolitan connections of the sort necessary to think “global” in the first place — resulted, renewing poetry as a site of hope, inquiry and vital connection for an international audience all too aware of our times crises and risks.

None of this is to say that Sun Dong’s poetry is about “the Anthropocene,” per se. Not at all. Sun Dong writes, moreso, in her recent poems, of love and family (including beautiful poems addressed to elderly, ailing or departed parents). She is playful and inventive, and her range of cultural references run from the Book of Genesis to Qu Yuan to Thoreau to bodiless lacquerware (脱胎漆器). The point is, rather, that this deep-time consciousness simultaneously grounds her poems in the physical world and lends a fluid, dissolving quality to them — a double consciousness that reckons with the profound ecological loss relentlessly accumulating around us, registering within us, and constituting us as we constitute it in the process of going about our quotidian business. Like the best poetry, her work is about being alive in the poet’s time — about embodied desires and loss, about the life of the mind, and life lived among and with others. This poet’s time, however, is “Spring in the Anthropocene.” Just as modernists worked to acclimate readers and publishers to work that left classical and pastoralist tropes behind in order to write the realities of the industrial age, or postmodern writers insisted on reflecting the shattering and fragmentation of grand narratives and the mirage of the “post-industrial,” this kind of work seeks to open our eyes to the realities of change, albeit change that registers in planetary geologic time as much as, if not more, than human-historical time.

Returning to a poem like “Thinking of Frank O’Hara Mid-Epidemic,” then, there’s something of the terrible human awkwardness inherent in blurting out a comment about, say, looming ecological catastrophe in the midst of a pleasant dinner among new friends and acquaintances while enjoying a beautiful view (something I refrained from while enjoying incredible home-cooked meals with my Chenjiapu hosts). It’s the mark of that nagging double consciousness of our time that reminds us that the energy we use today to peruse our phones and share photos of stunning landscapes contributes its little bit to the cumulative enormity of a growing human transformation of the planet into something post-O’Hara and post-Holocene, as the finale of “Thinking of Frank O’Hara” rather awkwardly notes:

...in a sense we're all winning

we're alive, though he died at forty

defeated by a reckless young coupleDefeated, we’re alive, at least

for nowToday, thinking of O’Hara again

I have to concede that I’m defeated by him

along with all those defeated others who say

in a sense

we all lose

……弗兰克 奥哈拉说

在某种意义上讲我们都赢了

我们还活着,可他四十岁就死了

一对轻率的年轻人打败了他可被打败的是他,我们还活着,至少

现在此刻今天,我又想起了奥哈拉

不得不承认我们还是被他打败了

我们中被打败的说

在某种意义上讲

我们都输了

The sense of loss that so many have felt as 2020’s coronavirus pandemic grinds its way through our lives, with all of its economic, political and psychological collateral damage, resonates throughout Sun Dong’s “early 2020 poems” (as if the first three or four months of the year comprised a full era — but isn’t that just it? The crisis accelerates, dilates, and elasticizes our perception of time to the point that it might as well be). The pleasures of the everyday take on a new valence in memory and in memorialization, as in “Forced Adaptation” (《应变》), which transposes a measure of O’Hara-esque urban excitement and compression onto her home metropolis, Nanjing:

Back then we’d find ourselves flush up against the piano in Shiwangfu

sitting at the top of the steps to the stage, which later became the spot at Wuyuecheng where we shared steak and onion soup before it became the movie theater where we caught whatever was showing before it in turn became the Lizhi Building我们曾在狮王府紧挨着钢琴的

中层台阶上落座,在同一地点的吾悦城里吃牛排喝洋葱汤又在后

来改成荔枝大厦的电影院

O’Hara’s present-tense excitement, here, has given way to Sun Dong’s backwards look, which isn’t just tinged with nostalgia (“Nostalgia” is the title of another of these poems, 《怀旧》), but also what Australian philosopher Glenn Albrecht has termed solastalgia, or "the homesickness you have when you are still at home" — an emotion arising less from missing the old days than, as it turns out, from missing the old planet. “Forced Adaptation” continues, picking up from memories of a Nanjing cityscape, encoded with deeply personal memories, that has transformed repeatedly:

So we’ve seen that movie already and the building goes nameless now

as we find ourselves mid-epidemic and recovery

lurks within its own latency看过电影而今这座没有名字的大厦

处在没有从疫情中恢复的

潜性当中

“Recovery” — 恢复— is by its nature hidden, as undetectable in its way as the virus was in its outbreak and spread, and the return to the normal, even the normal state in which one might indulge in nostalgia, is no longer there, even in moments of apparent domestic tranquility:

And now we’re home side-by-side frying up a few dishes

to cram into the overstuffed refrigerator

while downloading movies onto the computer while still watching

theatrical scenesSometimes we even mix the place names up

but maybe we don’t

really care我们现在在家里炒两个小菜

把冰箱塞得满满的

在电脑上下载电影甚至还能看

戏剧现场有时我们还会说错地名

但也许我们也不那么

真的在乎

Domesticity is indeed a temporary refuge, one in which many couples and families have found opportunities to renew connections frayed by the pre-pandemic pace of life, yet, in the wash of digital representations of experiences, of narratives of others’ fabricated lives, and of news of unfolding disaster, something goes missing and, it seems, will not be restored: the desire to go back, to return to “how it was before.”

Representations mediate experience in our social-media era even more intensively than they did in the recently departed television age, driving us deeper into distraction (technological hyper-mediation is another running theme in these poems.) And in the context of the rest of her 2020 work, it’s hard not to read “forced adaptation” as being about adapting to the Anthropocene and not just well-documented and commented-upon rapid transformations of modern urban space, or to a quarantine that will, eventually, lift and allow life to return to “normal.”

It’s easy to forget all this when, after months of confinement in the city, one has the opportunity to escape into “nature.” Chenjiapu offered that, despite my own sense of solastalgia and of living in shadowtime, of living in the Anthropocene which, by definition, means virtually no nature that hasn’t been altered at some level, visible or not, by humankind. It had stayed with me on the high-speed train as it raced through a countryside built up to an incredible degree, in which farmed land blurs into newly built high-rise apartment blocks, factories, power plants, high-intensity power line towers, and other features of eastern China’s intensive industrial development, flashing past travelers sitting, chatting on and staring at their phones. But that feeling did indeed dissipate as I walked into Chenjiapu — the car could take me no further — and down narrow stairs onto the path that led to my home for the next two weeks, with its view of mist-shrouded peaks and the calls of birds and drone of cicadas drowning out memories of the city’s clamor.

I might not have expected O’Hara, but I could have anticipated Wang Wei — along with Du Fu, Li Bai, Bai Juyi2 and a handful of other famous Tang poets. Sure enough, one evening mid-way through my stay, he came up in dinner conversation. My hosts and a few of their friends took turns cooking dinners served on an open-air table overlooking the valley. The meals were fantastic, often featuring vegetables raised in village gardens, bamboo shoots and other delicacies foraged from the forest accompanied by one of the chickens that range freely throughout Chenjiapu’s steep, winding lanes. A young entrepreneur hoping to launch his own bookstore and cafe was visiting to research Librairie Avant-Garde. He introduced himself as Ethan and joined us, eager to talk poetry and translation.

We were admiring the view as the setting sun cast dramatic shadows across the landscape when Ethan asked if I had read Nineteen Ways of Looking at Wang Wei, edited with commentary by Eliot Weinberger and Octavio Paz. The concept is simple. In chronological order, starting in 1919, Weinberger presents and critiques various translations of Wang Wei’s poem 《鹿柴》. The first edition ends with Gary Snyder’s 1979 untitled rendition; the expanded edition ends with 2006’s “Deer Park,” translated by J.P. Seaton. It’s a book that I love and frequently teach at NYU Shanghai. I responded to Ethan’s question with an enthusiastic “yes!”, adding that I was a bit surprised that he knew of the book. Native Chinese speakers can simply read Wang Wei, after all. His response surprised me more: “Oh, it’s quite well known here!” This minor mystery was cleared up for me shortly thereafter, when my hosts gave me the gift of the 2019 translation into Chinese of Weinberger and Paz’s expanded edition (which adds an additional nineteen translations). It’s a gorgeous edition, translated into Chinese by Guang Zhe (光哲) as《观看王维的十九种方式》.3

Wang Wei is, among other things, often thought of as a consummate nature poet, and 《鹿柴》— most often, but not always — translated as “Deer Park,” is as a good an example as any of why. Kenneth Rexroth’s title for his 1970 translation provides a clear example of how this poem imagines “nature”: “Deep in the Mountain Wilderness.” And when sitting by a clear-running stream a bit outside of Chenjiapu just below a small waterfall, looking out at the pine-studded ridges and bamboo-clad peaks rising above the valley below, I could almost believe that I was there, too, deep in the mountain wilderness, that I’d “escaped into nature.” But I was actually sitting on a slab of concrete presumably hauled up the ravine to help channel the stream, which waters the garden plots below. And I was online, no doubt thanks to that microwave tower just visible in the distance through the branches of a twisted pine. I could see a car, then a truck crawl along the two-lane highway on the valley floor as an airliner plowed the Anthropocene skies above, its contrail mingling with the high cirrus.

When did the Anthropocene begin? The current consensus is the mid-Twentieth Century, with fallout from nuclear weapons testing as a prime geological stratigraphic marker. But paleoclimatologist Bill Ruddiman argues that we can discern the beginning of the Anthropocene some 7,000 years ago, with the advent of widespread rice cultivation in what is now China and resulting spikes in the greenhouse gas methane, legible in ice core and lakebed samples. Ruddiman’s “early Anthropocene” theory has no chance of being endorsed by the international body of Earth System scientists responsible for the Geologic Time Scale (they’re currently considering whether to make the Anthropocene official and declare the end of the Holocene), but, as Simon L. Lewis and Mark A. Maslin note in The Human Planet: How We Created the Anthropocene, the theory “has been tested again and again, as all promising theories should be, and has emerged even stronger.” The point? We humans have been a planet-shaping force for a long time, and “nature” without some degree of human influence is, increasingly, a fiction.

In Nineteen Ways, Weinberger favors Gary Snyder’s untitled translations of Wang Wei’s 《鹿柴》, writing that it is surely “one of the best translations, partially because of Snyder’s lifelong forest experience. Like Rexroth, he can see the scene.” Snyder, however, sees it differently. He closes his 2016 essay “‘Wild’ in China” with his 《鹿柴》translation, commenting on how poetry like Wang Wei’s helped change his relationship to the idea of “nature”:

I first came onto Chinese poems in translation at nineteen, when my ideal of nature was a 45 degree ice slope on a volcano, or an absolutely virgin rainforest. They helped me to “see” fields, farms, tangles of brush, the azaleas in the back of an old brick apartment. They freed me from excessive attachment to wild mountains, with their almost subliminal way of presenting even the wildest hills as a place where people, also, live.

So instead of “wilderness” or “nature” as a landscape empty of the human, or within which the human plays a minor or even insignificant role, Snyder sees in verses like 《鹿柴》the indelible mark of the human: “Empty mountains: no one to be seen. / Yet — hear — human sounds and echoes. / Returning sunlight enters the dark woods; / Again shining on the green moss, above.” Even in “the empty mountains” of Wang Wei’s time, there were “human sounds and echoes.” Several scholars propose the sounds are those of woodsmen on Wang Wei’s estate whose job it would have been to cut trees, hunt, and otherwise manage the “wild” forest. One might speculate that Wang Wei, a devout Chan Buddhist, no doubt intended to present a kind of koan (from the Chan 公案 gōng'àn), a paradox of “emptiness” that gives rise to sense perceptions of the phenomenal world which necessarily fall back into emptiness.

Sun Dong is more of a city poet than a “nature” poet, though “nature,” as in a poem like “Fixed Gaze,” permeates her urban world. Her cosmopolitan verse references Eastern and Western literary, philosophical, and religious traditions with equal facility. She is not a Buddhist, though her work often draws on Buddhist philosophical themes and references, as it does in the final stanza of my favorite of her early 2020 poems, with its reference to 合十, which I translate as “palms pressed in blessing.” There’s no obvious Anthropocene reference here, though within the pattern of the set of poems the strange admonition to “inform those passers-by / who overdraw on spring, that night itself gives birth to night” does suggest that we have overtaxed nature, and, as in Wang Wei’s 《鹿柴》that our human strivings and desires have always-already fallen back into emptiness. I find it to be a beautiful, soothing poem, one that calms a mind agitated by reading of collapsing glaciers and ice shelves, of massive wildfires and heat-fed superstorms, and that says we may yet, together, somehow rise to meet the challenges that come with pandemics, ecological upheaval, and concomitant geopolitical strife. “Do you recall the bell,” it insistently asks, nudging me — and maybe you, too — from a moment of crisis-news induced paralysis:

Balloon with a Bell Inside

Day gave birth to night, night not fully formed yet

like bodiless lacquerware, a wisp of black limning the horizon

swelling, a pair of hands polishing it all to a high finishInform those passers-by

who overdraw on spring, that night itself gives birth to night,

like a balloon with a bell inside, so loud in the midst of its darkness that the deaf can hear it all

without themselves being able to form the slightest soundDo you recall the bell, speaking in a dream city of sleepless nights

one pair of hands polishing it all to a high finish

another letting spring rain fall from between palms pressed in blessing, the balloon slipping skyward

ringing & ringing

气球里的铃铛

昼生下了夜,夜还不稳

如脱胎漆器,一抹流动的黑色在天边

欲滴,有一双手打磨完毕把过路人的举动告诉

透支春天的人,当夜生下夜晚,

他们像气球里的铃铛,在黑暗中振聋发聩

却发不出半点声音你还记得那个铃铛,在梦里说着不夜城

一双手打磨完毕

另一双手让春雨合十,滑落在气球外面

叮咚作响

-

Che Qianzi’s first full collection in English translation, No Poetry, translated by Yunte Huang, is now available from Polymorph Editions. ↩

-

O’Hara identifies himself with Bai Juyi in his 1954 poem “To John Ashbery”: “I can’t believe there’s not / another world where we will sit / and read new poems to each other / high on a mountain in the wind. / You can be Tu Fu, I’ll be Po Chü-i…” Tang poetry in translation was in vogue among US American poets of the time. ↩

-

Beijing: The Commercial Press (商务印书馆), 2019. ↩

Comments

Pics look so nice!

Lirong, September 27, 2020, 1:52a.m.