A short time ago, the Paper 澎湃 ran an interview with Tao Yueqing 陶跃庆 about his work on On the Road, in which he explains what it teaches us about America, the afterlives of the book, and how gave up on translation for a day job. (《在路上》译者陶跃庆:凯鲁亚克及其燃烧的时代.)

I’ll admit, I am jealous sometimes of our Chinese comrades. I understand it’s not glamorous work (it’s my job!), but a book like On the Road is not waiting out there for me—a book the publisher has to hustle to get it into a second, third, fourth printing, a book appearing in the rucksacks of disaffected urbanites for the next two decades, a book that I will be interviewed about thirty years later...

Tao Yueqing had no idea that he had just helped launch an American classic in Chinese translation. He took his half of the manuscript fee and went on with the rest of his life.

Tao Yueqing’s 1990 translation (with He Xiaoli 何晓丽 [this is how she’s credited, but it was a typo: it should be He Xiaoli 何小丽], for Lijiang Press 漓江出版社) is considered by some (I mean Douban commenters here) to be the best version, but it was not the first.

The credit for that goes to Shi Rong 石荣 (the pen name of the duo of Huang Yushi 黄雨石 and Shi Xianrong 施咸荣), who had an abridged translation out by 1962 (听央视制片人讲翻译《在路上》的故事), only five years from the book’s publication in English. It was classified as for “internal circulation” 内参, one of the “yellow cover books” 黄皮书.

I’m imagining some young cadre picking it up on the recommendation of a liberal professor, hoping to find out what’s going on with American youth, and being either repulsed or fantasizing about hitchhiking down to Yunnan to smoke dope. These books were available to a small number of people, at first, but it was hard to keep a lid on that kind of thing. The yellow cover books ended up getting copied, usually by hand (《在路上》的精神史).

It was the English version of On the Road that Tao Yueqing stumbled across, though, in the library at East China Normal University. The Shi Rong version ended up being reprinted in the early 1980s, but there was no complete version to publish in book form.

Tao reached out to a friend that knew somebody at Lijiang, worked with He Xiaoli on a sample, and signed a contract in late 1988. They divided the work like this: she did the first chapter (it comprises a third of the book), and he did the remaining sections.

The payment was 3600 yuan, which Tao and He split equally (听央视制片人讲翻译《在路上》的故事).

He says in the interview:

My translation got published in December of 1991 and I got paid for it in March of 1991. If I hadn't translated it, I wouldn't have even noticed it had come out. I had taken a regular job and left the literary world. It was a government job, too, completely unrelated to literature. I was disconnected from all of that. Another factor is that the start of the 1990s was a fallow period in literature. I mean, there seemed to be nothing happening, no next wave... In the '80s, there was another wave crashing every year or two. By the time my translation came out, literature was already slowly slipping from its former importance. Everyone was suddenly worried about getting rich. The power of literature was weakening.

A third factor was that the publishing business and the media were comparatively old fashioned. Even a book as important as On the Road didn't get much of a publicity push. That's not to say that it had no influence on the literary world. It was selling, too. It was in its third printing pretty quickly, so that means they moved tens of thousands of copies. After that, though, there were issues with rights, so they had to shut it down.

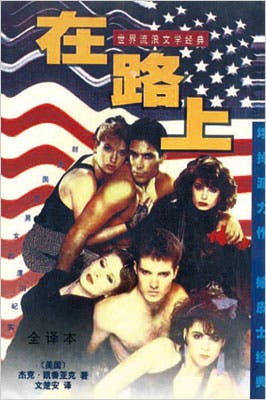

The cover was designed to fit in with all the 1990s "book stall literature" [地摊文学, and the cover image is the one you see above]. It was made to catch your eye while walking by. I think it also fit the impression many readers had of what the Beat Generation [垮掉的一代] was all about. That's what people thought On the Road was all about, what America was all about, what the Beat Generation was like... It's not so much that the cover art was inappropriate for the book, but it didn't give the impression that its contents were serious literature.

You might think there would've been issues with the sex, drugs, and bop in On the Road, but Tao points out that most of the necessary censorship was done long before he ever got the book, by American publishers:

Kerouac was under constant pressure from Viking to make changes. There were many changes made to his original manuscript. I don't think people realize, there isn't a single "fuck" in the book. The dirtiest he gets is "damn." There's not much in the book that would make anyone uncomfortable. Even the sex mostly takes offscreen. From the time Kerouac handed in the manuscript in 1952 to when the book was published in 1957, he was constantly deleting and revising.

Right before the book came out, the publisher panicked about the depictions of real people in the book. They had a lawyer get signed releases from them. He ended up changing all the names of his friends to pseudonyms. It's not as if it was hard to identify them, though. The publisher wanted to make sure they wouldn't get sued when everyone actually read what Kerouac had written about them.

Here, Tao discusses the way he approached the nitty gritty of translating:

In 1988, I sat down with He Xiaoli and talked over how we were going to do the book. We decided that we would stick as close as possible to the original. We wanted our version to be as close as possible to what Kerouac had written. We did our best to stay true to the original, but we did make some changes: English and Chinese sentence structure are very different, so there's a lot of inversion of order, and we sometimes decided to emphasize different things than Kerouac did, and on a grammatical level, we had to change some things around to make them work in Chinese.

On the Road is not a particularly literary work. It's a very straightforward narrative. It doesn't go into lengthy descriptions of its setting. As a translator, the biggest issue is usually with humor. That can be a real pain. Humor is so dependent on culture, language, and it's highly situational. Translating humor can be very difficult. On the Road didn't present many issues, though. That's partly down to how it was written, with Kerouac pounding it out all in one go. The narrative keeps driving you forward. Of course, I think part of it was also because we were young. The work resonated with us. It wasn't hard for us to imagine what the writer and the characters in the book were feeling. He was describing us, how we talked.

Tao and He went back to their day jobs.

Their translation slipped out of print for various reasons (I say "various reasons," but I have no idea precisely why, except some vague issue with rights 版权).

Wen Chu'an’s 文楚安 1998 translation (also for Lijiang) replaced the Tao-He version on bookstore shelves.

That was followed by Wang Yongnian’s 王永年 2006 translation (Shanghai Translation Publishing House 上海译文出版社).

I purchased a copy of that one, actually. It was with On the Road that I paid back the young woman that gave me a Carrefour flier-wrapped first edition of Ruined City and bought me a strung-up set of Outlaws of the Marsh off the street in Shanghai. (She hated it.)

The Wen Chu’an version was never highly regarded and went out of print; the Wang Yongnian translation held complete sway (except you could still read the Wen and Tao-He versions online).

In 2020, the situation changed completely. There's an On the Road "version war roaring. (《在路上》版本战.)

You can now buy a translation of On the Road by Chen Jie 陈杰 (Hunan Literature and Art Press 湖南文艺出版社), another by He Yingyi 何颖怡 (Booky 博集天卷), another by Yao Xianghui 姚向辉 (Jiangsu Literature and Art Publishing House 江苏凤凰文艺出版社), and, just last month, a fourth, by Zhong Zhaoming 仲召明 (Shanghai Purui Culture 浦睿文化)... and also, if none of those are appealing and you want to find out what everyone was talking about for thirty years, a reissue of the 1990 Tao-He version. (For what book translated from Chinese would that be possible? If a book comes out in translation from Chinese now, and you hate it, you have to know it's not going to be translated again in your lifetime. But just imagine!)

But I like that Tao Yueqing's literary odyssey has a happy ending: he translates a classic, wanders in the wilderness for thirty years, then re-emerges to his adoring fans.

Comments

On the Road was not the only novel translated by both Tao Yueqing and Shi Xianrong. See:

Holden Caulfield and the Chinese Shakespeare Scholar

Bruce Humes, July 13, 2020, 12:45a.m.