Welcome back to the Cold Window Newsletter! In this issue: the Beijing literary collective introducing dozens of Chinese writers to the world, and two novelists from Liaoning you should know.

A note on numbering: this issue is the second to be posted on Paper Republic, but the fifth I’ve written overall. Visit the newsletter on Substack to browse the archive and sign up for archives, including occasional smaller features that will not be cross-posted on Paper Republic.

Recommendation: Entering the Spittoon universe

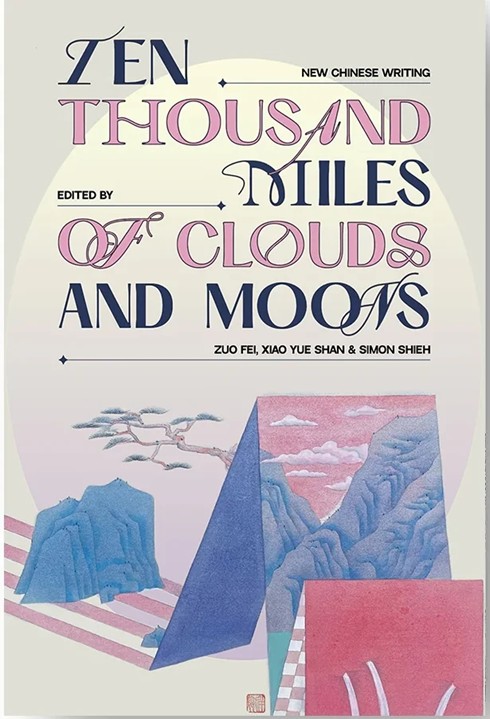

What is Spittoon? When I first came across its website in 2022, I thought it was just a literary magazine devoted to new translations of Chinese literature. We’ve had those before—pour one out for Pathlight and Peregrine, two beloved Chinese translation magazines from the 2010s—but rarely ones that boasted the same panache and gleeful oddness of Spittoon’s biannual offerings. Later I also found that Spittoon has also hosted regular poetry and fiction nights in Beijing for over eight years; has operated at least two separate literature podcasts; and, as of this past winter, has published a gorgeous new anthology of translated Chinese fiction, nonfiction, and prose called Ten Thousand Miles of Clouds and Moons: New Chinese Writing. I’ve emerged from my journey down the Spittoon rabbit hole dazed and bedazzled.

Ten Thousand Miles of Clouds and Moons: New Chinese Writing (2025)

The publishing arm of the Spittoon Arts Collective has a strong claim to be the most reliable resource on the English internet right now for discovering new Chinese writers whose works aren’t otherwise available in translation. The new anthology is a perfect example. Flipping through the table of contents yields a few familiar names, but my absolute favorite pieces were by authors and translators whose works I would never have come across otherwise. There’s “Pulling Thunder” 《引雷》, a strange tale about the art of harnessing the power of the heavens by Li Hongwei, translated by David Huntington. There’s a trio of gorgeous poems by Jia Wei, translated by Liuyu Ivy Chen, that range from Yunnan Province to the Susquehanna River. And then there’s “No One Sees the Grasses Growing” 《没人看见草生长》, a personal essay by Mao Jian (translated by Yiqiao Miao) about the disappearing generation of charismatic writer-professors (Ge Fei, Song Lin, Ma Yuan) who ruled the literary scene during her college years in the 1990s. Short personal essays do not quite occupy the same lofty position in the English literary world as they do in China—how many great essays like this must go untranslated as a result!

If you want to explore the Spittoon back catalog, you can start with Shen Danqi’s “A Reader of Translations (With Chinese Characteristics),” translated by Dave Haysom, or Suo Er’s “All the Whales Below the Surface,” translated by Irene Chen, Chen Bo, and Brandon Philen. Click around the website. Discover some new favorite authors. And when you’re ready, I strongly recommend checking out the new anthology. It’s available for purchase here.

Feature: Liaoning writers at large

A few months ago, I profiled Ban Yu and Yang Zhihan, my two personal favorite members of the critically acclaimed generation of young Northeastern Chinese writers who make up the so-called “Dongbei Renaissance.” Happily, both Ban and Yang were featured in English in a China-focused issue of Granta last fall, and I hear rumblings that there is a whole collection of translated Ban Yu short stories in the works. That means it’s time for me to turn my gaze toward two Northeastern writers who have received next to no critical attention in the West, despite writing some of the most moving, precisely crafted fiction in China today.

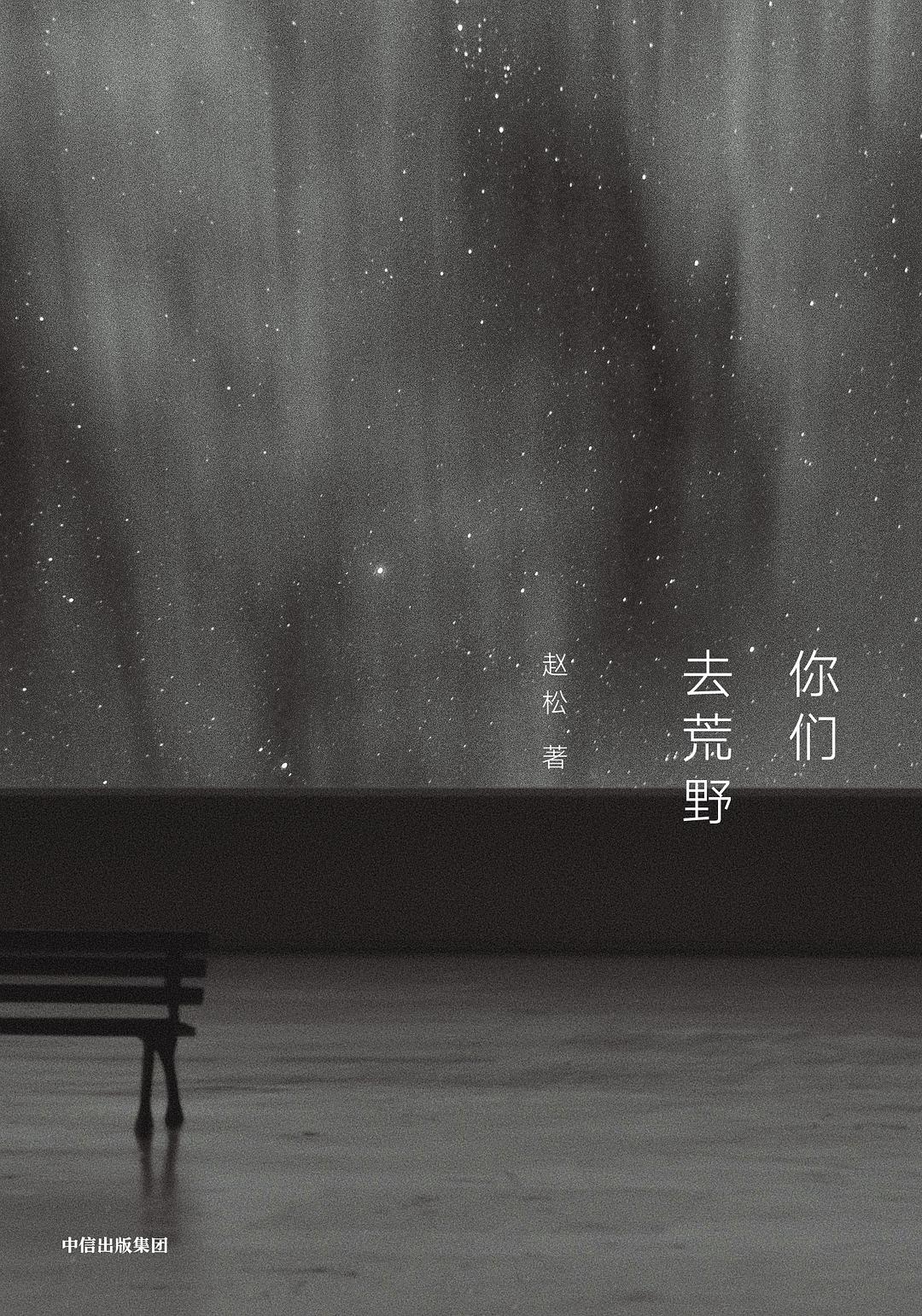

To call Zhao Song a “Northeastern novelist” might be something of a misnomer—although he was born in Northeast China’s Liaoning province, he has lived and written in Shanghai for many years and rarely uses the Northeast as a setting for his fiction anymore. To call him a member of the “Dongbei Renaissance” might be even more of a stretch, given how stylistically and thematically distinct his work is from blockbuster authors like Shuang Xuetao and Ban Yu. But I first encountered him via his 2015 book 《抚顺故事集》 Stories from Fushun, a collection of fleeting glimpses of the Liaoning city where he grew up, which for me is a defining entry in the canon of postindustrial Dongbei literature. In the wake of Stories from Fushun, Zhao wrote a series of challenging, critically praised novels before releasing the short-story collection that introduced me to his mature style last year, 《你们去荒野》 You Go into the Wilderness.

《你们去荒野》(You Go into the Wilderness, 2024)

The book takes its title not from one of the stories it contains, but from the Gospel of Matthew: “What did you go out into the wilderness to see? A reed swayed by the wind?” That gives you a sense of the style that Zhao cultivates in this collection: melancholy, erudite, and understatedly mystical, a bit like a Simon and Garfunkel song. Without a doubt my favorite story in the collection is 《盒子》 “Box”, which records the second-person narrator’s quest to track down people and artifacts associated with his girlfriend of decades before. She never appears in the story; since she refused to be photographed, we never even get a clear description of her face. And yet, through the slow accumulation of emails, anecdotes, and models that she designed in her aborted career as an architect, she gradually begins to feel like a realer and more powerful presence than any of the people she left behind. In my favorite passage, forbidden from photographing her face, the narrator builds an indirect portrait of her via snapshots of the things he notices her looking at:

That’s the sentence that fully sold me on Zhao Song. It feels like a natural development of the brief, meditative portraits on ordinary people and places that made up Stories from Fushun nearly ten years earlier. Highly recommended.

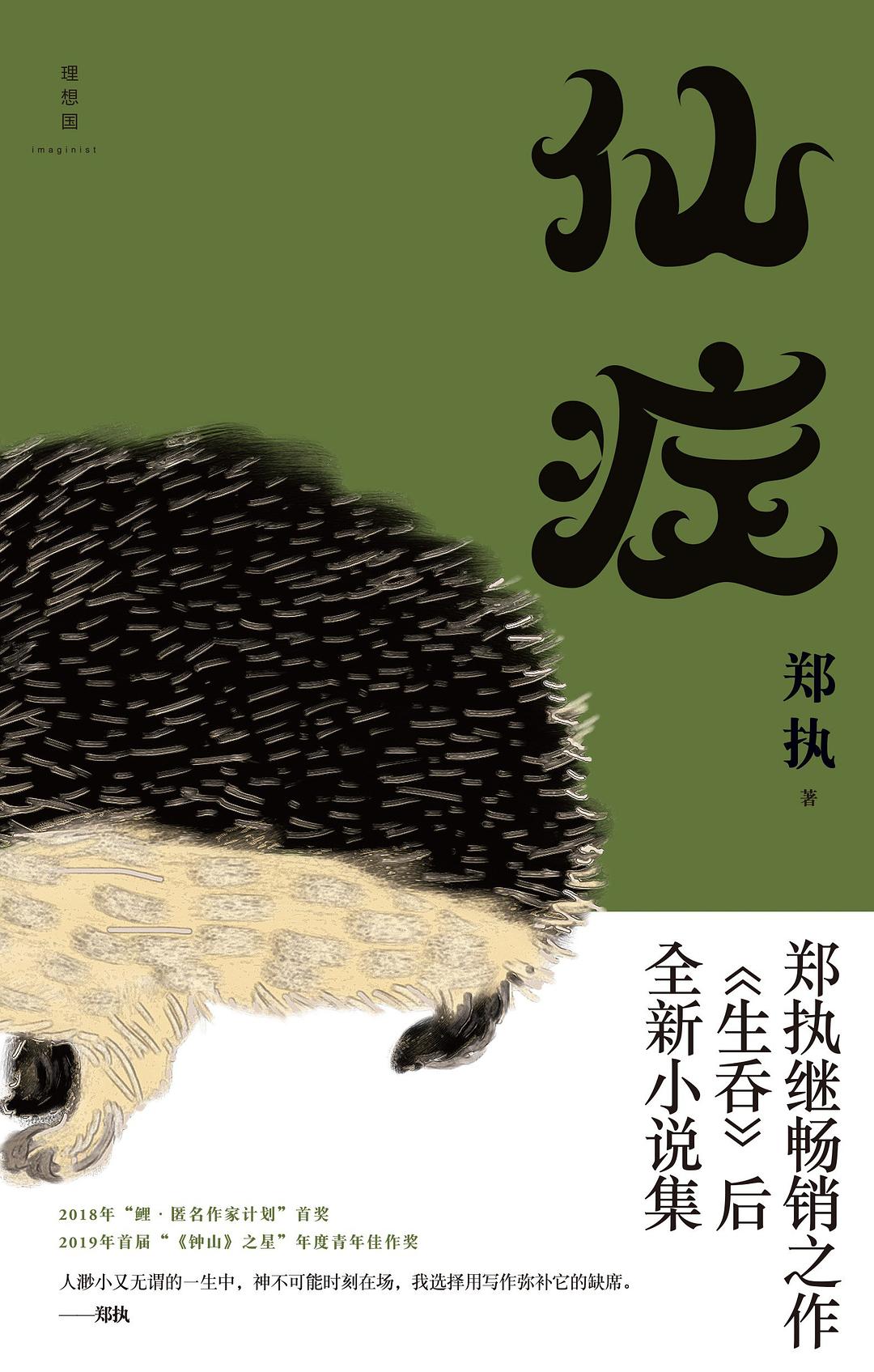

Whereas Zhao Song is a dubious representative of the Dongbei Renaissance, Zheng Zhi is an undeniable icon of the movement, and yet he continues to have almost no name recognition outside of China. He was the last of the “Three Swordsmen West of the Tracks” (铁西三剑客, the others being Shuang Xuetao and Ban Yu) to have his major work translated into English, with an English version of 《仙症》 “The Hedgehog” (translated by Jeremy Tiang) finally out in the Paris Review just this spring. One of my favorite amateur literary critics recently made a convincing case for 《生吞》 Victim in Me, Zheng’s 2017 suspense novel, as a defining novel of the Dongbei Renaissance. I haven’t read Victim in Me yet, but I can tell you that the stories in Zheng’s 2020 collection 《仙症》 Divine Disease are some of the most exquisite writing that this generation of Dongbei writers has produced.

《仙症》(Divine Disease, 2020)

People will try to tell you that “The Hedgehog” is Zheng Zhi’s best short story. It’s the one that the collection is named after, it inspired the book’s delightful cover, it’s been translated by one of the world’s best translators, and it was turned into a film last year (under the title 《刺猬》The Hedgehog). It’s a good story. It delves powerfully, à la Ban Yu, into the relationship between the laid-off workers of the economic crash of the 1990s and their children. If you’ve ever wondered what sorts of spiritual ailments might befall you for eating hedgehog meat, it’s a must-read.

But my heart belongs to 《森中有林》, the collection’s closing novella. (This is a tough title to translate. Maybe “Forest in the Woods”?) At first the novella is about the unlikely friendship between Lü Xinkai and an elderly prison guard named Lian Jiahai, whom he accidentally injures with an air rifle during some illicit target practice. As time passes, Lian Jiahai’s blind daughter Lian Jie enters the cast, followed by her son with Lü Xinkai. The scope of the novel expands rapidly as Zheng teases out the relationships between all these characters, not unlike a lush forest sprouting up from a sparse patch of woods. Given how much narrative heft he’s able to muster in under a hundred pages, you begin to see why Zheng is the only one of the “Three Swordsmen” yet to have written a full-length novel. How long will we have to wait for the next one? (If it takes a long time, at least we may have a film version of 《森中有林》, written and directed by Zheng himself, to tide us over in 2028!)

That’s all this time. Visit the newsletter on its home site to read the archive and subscribe for future installments. In next month’s full issue: some of the early literary hits of 2025, and a tentative first foray into the massive world of Chinese internet fiction. Thanks for reading!

Comments

There are no comments yet.