Welcome back to the Cold Window Newsletter. This issue, a hodgepodge: first, the state of translation in the world of internet fiction; second, reviews of two short-story collections squaring off for a major literary award next week.

This is the fourth installment in my on-again, off-again series on Chinese internet literature. If you want to read more, start at the beginning.

Thirteen ways of looking at Chinese internet literature: translation edition (#7-8)

Translation is important. But getting English-language publishers and readers to take a chance on translations from Chinese has historically been very difficult. Despite some progress, only a few dozen Chinese books make their way into English every year, largely by older and male authors. To sustain a large, healthy community of professional translators, we need more.

So the fact that, out on the internet, there is a whole other world of Chinese-to-English literary translation—dwarfing the formal translated book market in terms of number of translators, number of translations, and very likely number of readers—is nothing short of miraculous. It’s a miracle that deserves celebration, and also closer critical scrutiny.

Way #7: Internet literature as a bustling translation ecosystem

The history of fan translation of Chinese internet literature is almost as long as the history of Chinese internet literature itself. As early as the 2000s, bilingual readers of wuxia fiction, most of them Asian-American, were already doing the herculean free labor of translating whole 金庸 Jin Yong and 古龙 Gu Long novels on forums like SPCnet. (Some of these early unlicensed translations have been archived by fans online and, for some classic wuxia novels, remain the only way to read these stories in English.) Around 2010, fans began translating some of the monstrously long internet novels that were already dominating online spaces in China. Qihuan (奇幻, or Western-style fantasy) novels like 《盘龙》 Coiling Dragon by 我吃西红柿 I Eat Tomatoes, translated on SPCnet by RWX in 2014, went especially viral and contributed to the popularization of internet novels in the West. (For more detail on this history, I recommend research from the WeChat account 媒后台: “媒介革命视野下的中国网络文学海外传播”; “网文史话 | Wuxiaworld”.)

By the end of 2015, there were three relatively large sites dedicated to fan translations of Chinese internet fiction: Wuxiaworld, Gravity Tales, and Volare Novels. Of the three, only Wuxiaworld survives to this day, now joined by Webnovel, the international arm of the Chinese internet novel giant Qidian 起点.

Dedicated internet novel translation platforms, past and present.

Online translation has now matured from a hobby to a business. Wuxiaworld no longer hosts free, unlicensed fan translations; it now legally licenses novels and hires translators to bring them into English at a chapter a day, often for years at a time. Webnovel also hosts licensed, paywalled translations of many of China’s most beloved novels (albeit often with a strong AI-translation flavor and a tendency to halt without warning in the middle of serialization). Some translated novels, nearly all of them danmei, have even gained enough of a market to get picked up by print publishers and appear in bookstores and libraries in the West.

Through all of this, fan translation remains the unacknowledged backbone of the translated internet novel ecosystem. For all their growth in the last few years, licensed sites like Wuxiaworld and Webnovel are only large enough to capture a tiny fraction of China’s best internet novels, and their all-but-declared focus on 男频 (male-reader-oriented) genres excludes a huge swath of worthwhile novels from ever getting an official translation. To read nearly anything new, or queer, or 女频 (besides danmei), or lying outside of established genre boundaries, we still rely on fan labor.

Yes, fan translators work outside of legal copyright, and there’s massive variance in the quality of their writing. But in their dedication to patching holes in the translation landscape and their ability to energize huge numbers of readers, they’re handily achieving things that translators in the formal publishing market have struggled with since time immemorial.

Way #8: Internet literature as an impossible translation conundrum

And yet.

There’s nothing that I want more than for the energy of internet novel fans to bleed over into other types of literature and spur popular interest in Chinese stories as a whole. But internet fiction and traditional literary fiction have fundamental formal differences, and success for one does not necessarily spill over into success for the other.

A handful of the fan translation resources I’ve used to browse internet novels. Some good, some less good, all products of extreme fan dedication.

The most obvious of these differences is the means of distribution of internet novels. Whether in Chinese or English, these novels are serialized in bite-sized chunks and stretch out over hundreds of thousands of chapters; they accrue fanbases because they are written quickly, updated constantly, and free or nearly free to read. If you try to make the novels conform to the conventions of traditional literature—either by enforcing copyright, or taking the time to do real editing, or charging enough money for the translator to make a decent wage—there’s a risk that readers will simply switch to a pirated edition or, worse, drop the novel entirely.

These bad incentives put internet novels at grave risk of being flooded by sloppy AI writing. Machine translation, broadly speaking, is not yet welcome in the traditional literary market. But on licensed online translation sites—in practice, that means Wuxiaworld and Webnovel—you can often tell that the human translator has used AI to speed things along. And on some fan translation sites, even the ones that don’t declare themselves MTL (machine translation), nearly every sentence carries an unmistakable AI flavor.

The spread of AI translation is unsurprising in a literary form that relies so heavily on speed, volume, and cheapness. But relying on AI dooms these translations to be rejected by literary readers. And that’s a shame, because internet novels are otherwise such an intuitively fun and welcoming entry point into Chinese literature. If they’re hamstrung by clunky AI translation, a golden opportunity to reach more readers will have been wasted.

So what can we do? Promote good translation. Wuxiaworld and Webnovel: invest in your human translators and editors. Publishers: learn from danmei and put out print runs of high-quality human-translated internet novels to attract new audiences. Fans: keep translating. Good stories conquer all.

Feature: Short Fiction on the Blancpain-Imaginist Prize Shortlist

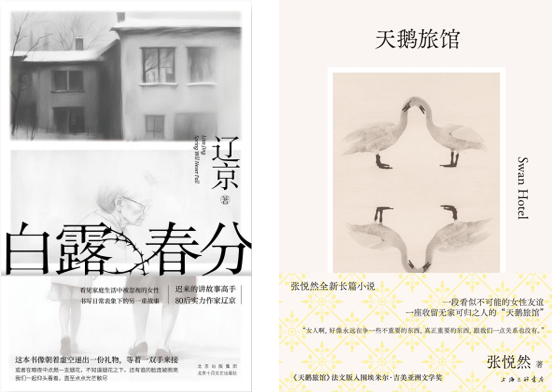

Just a quick pair of author features this time around. The shortlist for this year’s Blancpain-Imaginist Prize was announced late last month, and, to my amateur eye, the two novels—辽京 Liao Jing’s 《白露春分》 Spring Will Never Fall and 张悦然 Zhang Yueran’s 《天鹅旅馆》 Swan Hotel—look like the clear frontrunners. (The latter book, out in English in Jeremy Tiang’s translation as Women, Seated, must be the first Blancpain nominee ever to have an English version published before the prize is even announced, which is quite exciting.)

The novels with the best shot at next month’s award: 辽京《白露春分》(Spring Will Never Fall by Liao Jing, 2024) and 张悦然《天鹅旅馆》(Swan Hotel by Zhang Yueran, 2024).

But three short story collections remain tenaciously in the running. One of them, 邵栋 Shao Dong’s 《不上锁的人》 Those Who Leave the Door Unlocked, won my seal of approval back in August. The other two are by authors whom I’m only just now hearing about for the first time. An award nod this early in their careers means it’s a good time to get acquainted with their work.

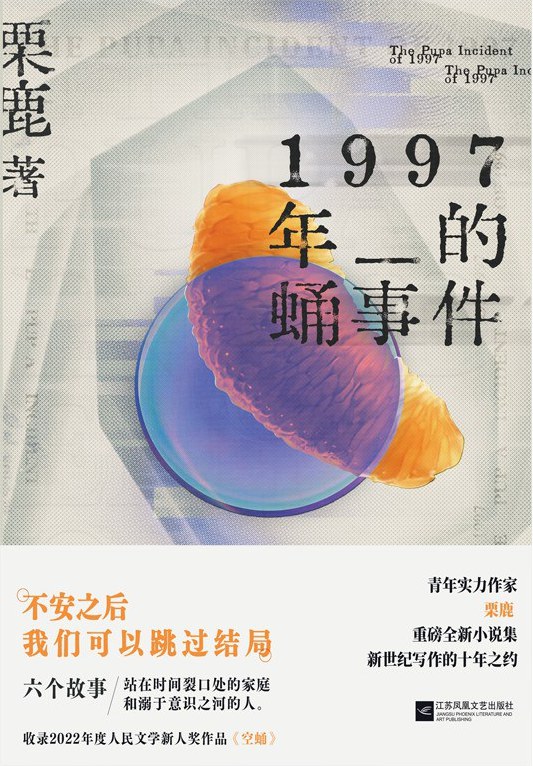

I still haven’t quite recovered from reading a few stories from 《1997年的蛹事件》 The Pupa Incident of 1997 (great title) by 栗鹿 Li Lu (great name). There are writers who know how to be so unsettling that you doubt your grasp on reality, and then there are writers who know how to be outright scary. Li Lu can do both.

栗鹿《1997年的蛹事件》(The Pupa Incident of 1997 by Li Lu, 2024)

《空蛹》“Empty Chrysalis,” the story that gives the collection its name, has drawn comparisons to Borges, but I think it’s more like Kelly Link, or H. P. Lovecraft, or SCP Foundation creepypastas. And I mean that as a compliment. After an indescribable shadow passes over the sun in a small seaside community, its residents begin to suffer what the authorities term “information contamination” 信息污染—inexplicable changes in people’s memories, names, written records, house numbers, all with no indication that things were ever otherwise. One character wakes up to discover that she lives with her sister, whom she clearly remembers died in infancy; another changes his name to that of his dead brother, merging their two identities awkwardly into a single body. It’s terrifically frightening. I almost want to give Li Lu the award right now, just for making me feeling something.

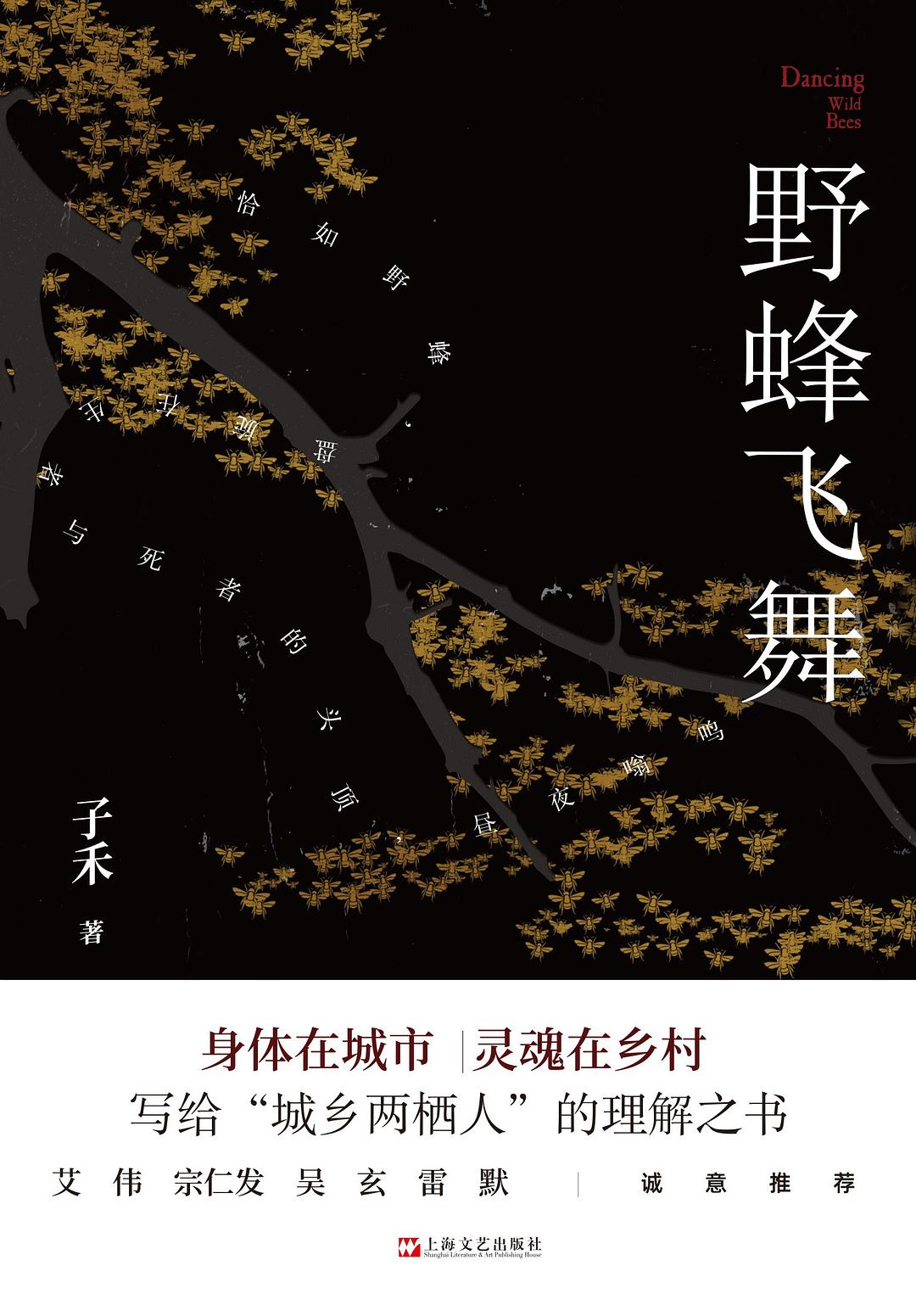

As far on the opposite side of the literary spectrum as it is possible to be, we have 《野蜂飞舞》Dancing Wild Bees, the debut collection by Gansu native 子禾 Zi He. His fiction might not appeal to everyone. Languorous in pace and introspective in tone, it seems intent on giving its taciturn, working-class characters the space they need to express themselves fully, even at the expense of plot.

子禾《野蜂飞舞》(Dancing Wild Bees by Zi He, 2024)

In the title story, “Dancing Wild Bees,” a young man visiting his hometown from the city pays a visit to his aunt and uncle, the parents of a cousin he had been close to as a small child. The action never moves from their small rural home, and the aging couple’s forced attempts at hospitality, rendered unflinchingly in Zi He’s straightforward style, can be hard to bear. But there are little moments where the adults let their guard slip, allowing their nephew an accidental glimpse into the crushing loneliness and regret that they’ve tried everything to hide. It’s the most restrained and empathetic story I’ve read in a while—not flashy virtues in fiction, but virtues all the same.

Look out for the award announcement at a livestreamed ceremony on November 1.

That’s it for this issue. As always, you can visit the newsletter on Substack to subscribe for updates and read shorter interim issues. Thanks for reading.

Comments

There are no comments yet.