The man says, I want to make a gate this big.

The woman asks, what gate?

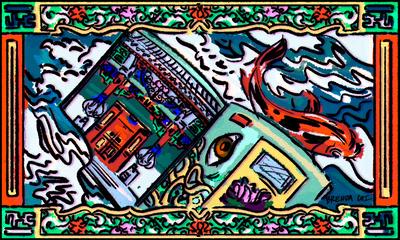

The gate was in a colorful two-page insert. It was a resplendent Qing dynasty hanging flower gate, the kind with a front door, back door, and side doors leading to covered walkways. The lintel is painted with rolling clouds, and the front pillars, instead of coming all the way down to the ground, hang halfway, their ends carved into lotuses with nine layers of petals and sepals. Such a beautiful gate, folded away in a magazine, fluttering down to rest on the cold hard floor. This isn’t the sort of door you normally see in a modern home magazine. What people seem to need is hefty security doors, high-quality wooden doors, elegant sliding doors, and those new movable panel doors. That’s what the woman needs. She scoops up the magazine that the man, while gesturing with both hands, has dropped, and with a short angry snort, opens it, and says to the man, this is the kind of door we need.

I know, the man says.

If you know it, then get on it. If you haven’t chosen in three days, I’ll choose, the woman warns the man.

The doors in this magazine are all expensive, made from rare wood and fine fittings. For most families buying the magazine and planning their new homes, it’s just a printed version of their distant dreams. On a typical quiet evening, in modest apartments all over the country, women snuggle up to men, and in the dim light of bedside lamps, point at woollen rugs on black walnut floors, plush sofas, as if they’re moving into a place that big tomorrow. This man and this woman have a place that big, but the magazine is laid out under a sputtering lightbulb, and discussed in a businesslike manner. Discussed until almost ten o’clock, at which point the woman becomes sleepy. She goes alone to take a shower, goes alone through her skincare routine, takes the magazine from the man who is still sitting on the sofa, goes alone into one of the bedrooms and shuts the door with a click.

It’s a typical thin MDF door, its deep grain produced at high temperatures in a machine. When the man presses his ear to the door, he can hear the deep breathing of the sleeping woman on the other side.

The man hates these cheap doors, the cheap ones often don’t hang straight, they’re only good for hiding nasty, pathetic secrets, produced in a cheap and dirty industrial process. Just like those cardboard-thin sliding doors and wardrobe doors. There’s a thin wardrobe door like that in the bedroom, printed with a floral design to add a bit of class. Once when the man came home from work, he heard a banging noise coming from the bedroom. Soft moans, feet hitting the foot of the bed, the scrape of a belt being picked up, and finally the wardrobe door sliding open and shut. The man listened quietly for some time, and the only note out of place in this brisk melody was the hurried whispering of the woman and another man. The man walked into the bedroom, and found the woman breathing heavily, folding pillowcases on the bed.

The man asked, what are you doing?

The woman took a breath and said, I’m just tidying the room.

The man walked around the foot of the bed to the front of the wardrobe door, walked one way, then the other, and finally stopped. Above the floral print fiberboard, the top half of the door was frosted glass. Usually, behind the frosted glass, you would see a row of hanging suits and dresses. And there they were. But the man approached the glass suspiciously. Through the translucence, the man made out a pair of eyes. Delicate eyes, not like a man’s. The eyes stared back at the man, motionless, until with a blink, one long, thin eyelash came loose, and sank into the darkness.

The woman waited silently until the man finally said, let’s go out and eat.

Outside their apartment complex, there is a street of busy restaurants. Beyond them, an avenue, part of the university. The man often follows this route from the complex to the back gate of the university, leaving the smell of rice noodle hotpot to walk into the mountains. That is, the mountain behind the university, desolate, deserted, the birds squabbling. The setting sun picks out the withered leaves in their isolation. Here the sky is blotted out by many tall trees, the right kind for making doors. Every time the man sees them, he feels there’s a crowd of doors standing silently on the mountain. The doors overlook the men’s dorm at the bottom, which is surrounded by a rudimentary flower garden. In spring, the garden draws a flock of white butterflies. One of them makes its way down the hill, through the back gate, through the smoky hubbub of the restaurants, through the main gate of the apartment complex, and flies into its locked inner recesses, seeking out the most secretive, most fragrant white blossom. The man, as he follows the butterfly, thinks there may be another man, who, like this bobbing butterfly, passes through one gate, two gates, and finally penetrates his secret garden.

The man’s cousin had a lot to say about the complex’s main gate. The man pulled out a small disc on a keychain, held it next to a panel on the gatepost, and the iron gate trundled open noisily. The cousin shook his head, and said, wow, high tech, that’ll keep out the bad guys. He was impressed, though, by the landscaping inside the complex – the sculpted rocks, flowing water, curving bridges, lakeside wildflowers, and soaring skyscrapers. The cousin said, bro, this place has more natural rustic charm than our village. In his left hand, the cousin was holding a plucked and headless chicken ready for the pot, and in his right, a bag of fruits and vegetables in various shades of green. The chicken had been freshly killed that morning, and the vegetables were freshly picked. The cousin marvelled at the highly polished elevator walls, watching the man press the button for the 17th floor. The cousin said, 17th floor, huh? I’ve never been that high, not even in the mountains. Uncle Wang has only just added his fourth floor this year.

The man asked, why have you come?

Bro, aren’t you moving house?

Not yet.

Didn’t you tell my mother it was this Saturday? I brought a house-warming gift.

The date’s changed, didn’t I tell you guys?

No, when is it now?

Haven’t decided.

What’s going on?

Haven’t finished renovating. The doors haven’t been installed.

What? Still messing around? How hard is it to pick a door?

Ah, you don’t understand, the man said.

The man asked the cousin to come in, and offered him a pair of jade-green slippers from the shoe rack. The slippers had clearly been worn by someone with big feet, and fit quite loosely even on the cousin. The man took the chicken and vegetables from the cousin’s hands and walked into the kitchen. The cousin looked at the snow-white walls, the soft carpet. He couldn’t quite sit down, nor could he stay standing, but just clenched his fingers and paced the front hall, spellbound by the slippers. The cousin said, these slippers are so big, I remember when we were small, when we played outside, you had the smallest feet. They say that men with big feet walk the farthest, and sure enough, you were the only one who managed to leave the village. How did your feet get bigger than mine?

The man shuffled out of the kitchen in a pair of dark brown cloth slippers. His feet were no bigger than a woman’s. The man poured a glass of tea for his cousin. The man said, sit down, don’t just stand there. The cousin sat embarrassedly, cautiously stroking the sofa. It was a white leather sofa, no longer plump, in fact a little saggy. Its surface, having been crushed repeatedly by the weight of people, was showing millions of tiny cracks. In the countryside, cracks like these only show in the dry season. The soil no longer has any moisture, and is riven by thousands of fissures. The cousin’s mother dreamed about it one night. Dry cracked mud stretching for miles. It scared her so much she got up silently and went to the next room to feel if her son was still there. That sort of memory lasts for generations. For a while, the cousin’s mother stopped eating meat, said Buddhist prayers, and recited sutras in front of a Buddha statue in their simple cottage, praying that her grandchildren would someday, like the man, make it to the city. The city isn’t that far, just outside the village, turn right, and get on the White Rhino Ferry. For just one yuan, it goes along the winding river to Nine Dragons Shoal. Nine Dragons Shoal is the next commercial and residential area to be developed. There’s going to be a high speed rail station next to it. At the moment, it’s just overgrown. The cousin caught a direct bus here from the ferry pier, and along the way he saw building sites covered with tarpaulins, with scattered piles of building materials. The previous time, the cousin had also come that way. He’d carried a slaughtered and plucked chicken, and was stopped at the gate of the complex. The distrustful security guard buzzed the apartment to confirm his identity. The woman answered, not the man. The woman told him the wedding reception was about to start, and told him to take a taxi directly to the hotel. At the hotel they had a luncheon, then a dinner banquet, and lunch the next day. It was as extravagant as something on television. The music and singing went on and on, and they kept soaking it up. That was in the height of the summer harvest; after the dinner banquet, the cousin drifted back up the glossy black river on the slow ferry. He’d never been past that main gate until today, and only now saw for the first time the scenic artificial mountains and water features, the neglected sofa, and the tiny Swiss cheese plant in the corner of the balcony. The kind of souvenir a hotel gives to newlywed guests. It hadn’t been watered in a long time, and its brittle yellow leaves swayed in the sunlight.

The cousin said, bro, I want to get married too.

When?

Still haven’t picked the day. End of the year, or early next year. That’s supposed to be a good time to do it.

So you’ve got plenty of time.

No, it’s not that far off. You don’t know, these days village weddings have to be prepared way ahead. You get a little busy and suddenly it’s time.

Well, when it happens, give me a call and I’ll be there.

Well okay, bro, it’s just…

What is it?

The house isn’t finalized.

What’s the problem?

My family’s only got so much land, we’d have to tear down the old house to build a new one, and my parents wouldn’t have anywhere to live. Her family wants us to be in a proper house… bro, don’t you still have that courtyard house? Aunt and Uncle aren’t there any more, and you’re living here in the city. I just thought, you know, that house of yours…

You want to move into my house when you get married?

Yes, yes, just at first, just to tie the knot. Later, we’ll see.

The man didn’t say yes, nor did he say no. He paced back and forth in front of the cousin a few times, inscrutable. The man’s reflection on the flat-screen television became blurry, stretched, indistinct. The cousin finished off the cold tea in one sip.

The man suddenly asked, how did you get here?

Huh? The cousin stared.

The man asked, did you take the boat?

Oh, yeah.

Is it still the White Rhino Ferry?

Uh-huh.

I remember the house was just behind the ferry pier. Wasn’t it flooded two years ago?

No, it’s all behind berms. We’ll look after it for you, we’ll fix whatever’s broken. It’s still standing. With a little tidying it’d be ready to live in.

Nothing’s broken?

Broken?

The gate is still good? the man asked.

The cousin said, what gate?

That night, the man had a dream. He paid the boat fare and set off from Nine Dragons Shoal. There was one ferryman, in black rain gear, in the back of the boat, and the man stood up front. The boat squeezed between the two steep shores, like the spines of great beasts, while a school of insubstantial fish swam under the surface of the twilit water. In the rainy season, the raging schools of fish can give you hints about water levels along the river. The boat bumped against the top step of the ferry pier, the lower steps submerged. The man made out the tall, dark embankment. And past the embankment, that big courtyard house that had silently seen off so many generations of people. The white-walled, black-roofed main gate facing auspiciously to the south-east had once rung with the welcomes and farewells of many honoured guests, but there was little left that anyone would want. To the man, it was perfect, except for the hole where the hanging flower gate should be. The hanging flower gate, separating the inner courtyard where the women stayed from the outer courtyard where guests were received, should be the most beautiful part. At night, with the door to the outer courtyard closed, and the inner green doors shut, the hanging flower gate became a tiny pagoda, an impenetrable box. Inside it, a person could be strangled to death by someone else, or they could make it safely to heaven on their own. Now, the courtyard didn’t have such a box. In his dream, the man, with a tile cutter and wooden mallet in his hands, built a hanging flower gate like that in the darkness.

Harsh knocking woke the man from the dream he didn’t want to leave. The woman, who had been out all night, stood in the doorway, knocking on the flimsy MDF door.

What are you doing sleeping in my bed? the woman said, looking at the man curled up on the bed.

My cousin came. He’s sleeping in my room.

Why has he come?

He wants my house.

Your house? You mean that old dump in the village? How much is he paying?

He doesn’t have any money. He said he wasn’t busy so he came up to help me with stuff.

He wants a house for free?

He needs a new house to get married.

Huh, the woman snorted, how is he going to get married without money?

People without money still have their no-money logic. Outside the gate of the complex, there are moneyless people everywhere. The guy that runs the little shop doesn’t have money, so he opened it in the twisty alleys beside the complex, a rented hole, and sells spicy potato noodles for six yuan a bowl. The students who come to slurp the noodles don’t have any money either, so they walk down the road from their dormitory on the mountain to this dirty alleyway, to eat the cheapest noodles. The man took his cousin there to eat, a grimy fan swinging back and forth overhead, a warm breeze stirring the dust outside the door. The man remembered that he installed the glass door here, taken without alteration from the abandoned cold noodle stand next door, so he just charged for the installation.

The cousin lifted his head from the noodles, and said, bro, you’re door-mad.

What do you mean, door-mad?

Didn’t anyone ever tell you? That’s what everyone in the village calls you.

You can be piano-mad, painting-mad, book-mad, chess-mad, whatever you’re obsessed with, you can take it to high levels of talent and sophistication. Unfortunately the man is door-mad. When he was small, he would squat on the mat in the main room, beside the entrance screen, watching how all the doors, big and small, would open and close, watching how a certain hinge would make a creaking sound, watching intently until his mother would smack him in the face, scolding him, you, you’re door-mad! What has this family come to? When part of the covered walkway encircling the courtyard collapsed, the whole thing was pulled down. The ornate hanging flower gate was turned into a humdrum door in the wall. This scholarly family decided to hobble itself, and hobble its future generations at the same time, to avoid an even worse calamity. This shock drove the boy’s obsession deep into his bones, so he could concentrate on his books, and get safely across the winding river to the city on the other side. It was only when he met the woman that his madness burrowed back to the surface.

The cousin said, I gotta explain something to you. Sure, doors are interesting. But nobody wants to hear you talk about them.

The man asked, what are you talking about?

The cousin said, I don’t understand door stuff. But I know how things work when it comes to men and women. Sister-in-law didn’t come home last night, did she? And she usually doesn’t cook for you? A man gets married, but his wife doesn’t cook, so he’s forced to go out to eat. People start talking about it.

The man said, for someone who isn’t married you talk like an expert.

The cousin sighed, this doesn’t have anything to do with whether I’m married or not, this is how it works.

Your sister-in-law doesn’t like cooking.

Who does? If you want to hook up and live with someone, you’ve got to lay down some rules. Without rules, it’s game over. Training a woman is like training a cat. If you don’t break her in before getting married, she’ll be even wilder once you’re hitched.

The man laughed, and said, you seem like you’ve got a lot of experience.

The cousin became more animated, took out his phone and showed the man Lily’s photo. Lily was the cousin’s fiancée. The cousin said, women need to behave. If they don’t behave, beat them till they do. The man leaned in to look. In the photo, a girl was climbing a peach tree in an orchard, the young peaches, hanging green and firm overhead, highlighting Lily’s rosy, sweet smile.

On Sunday, the cousin goes with the man to install a gate at a villa. The cousin has been offering to help with anything and everything for the last week. The man’s shop is full service, and when he installs a door for someone, the cousin carries it. But as for that courtyard house by the ferry pier in the village, the man is no closer to a decision.

The villa is in the south of the city, exactly opposite Nine Dragons Shoal to the north. With this class of villa, every brick, tile, door and window is chosen by the owner according to their taste. In the past, people would choose between a roomy Guangliang gate and a slightly less extravagant Golden Pillar gate, but nowadays they choose between Chinese or European style copper or aluminum gates. The type of gate tells the world what kind of person lives behind it. The man is fondest of hanging flower gates. These are the only ones that don’t show the world anything. While the front entrance is modest and low-key, the hanging flower gate, within the house, is a thing of beauty. Only those who have been invited, who have come to discuss things, can see that this family is so accomplished, so elegant. The man initially recommended a copper gate to the villa owner. Oh, such an impressive copper gate, with deep, complex engraving that you have to lean in, look closely, rub it with your hand, to see the subtle refinement. Throw in the German-brand fingerprint recognition system, when you come home from work, just press on the handle, and with a beep, your vast gate opens effortlessly. Modern doors are beautiful at rest, and beautiful in motion. If you want beauty you have to spend money. The lady of the house surreptitiously tugged the sleeve of the wealthy businessman, pursed her lips, and gave a slight frown. Pointing at another gate in the display, a brilliant glossy white aluminum decorated in dazzling gold, about which there is nothing to say, she said, let’s get that one.

While the man installs the gate, he talks doors with the cousin. Or rather, he talks about beauty. If someone is mad about something, then whenever they talk about it, they’re very eloquent, because what they’re talking about is beauty. The cousin has no interest in doors, but he’s interested in the mud in front of the door, and the slapdash flower bed, and the woman who lives upstairs running the air-con. She doesn’t give them any food, just drives off alone at noon to a banquet in town. Leaving them to go several kilometres to eat some McDonald’s hamburgers. The man buys two burger meals for the cousin. The burgers are small, and the cousin gets through them in two or three bites. People who are used to farm work don’t know when to stop. The cousin happily gulps down two cups of soda, belches, and asks the man, that woman, have you figured it out? She’s his mistress.

What mistress, watch what you’re saying. The man glares at the cousin.

I mean a slut, a whore, his bit on the side.

The man scolds the cousin, we’re here to install a door, not to gossip.

Yeah, yeah, I’m just telling you. I just can’t stand women who sleep around like that. How is a low-class woman like that living in such a big house?

So now you’re the expert on who’s low-class, and who isn’t.

What’s it look like to you? the cousin says confidently, showing off your wealth like that is definitely low-class.

The man doesn’t reply, but focuses on chewing his hamburger. The cousin looks around, then says carefully, bro, you know your neighbors also say you’re door-mad?

The man asks, who says that?

Just the doctor upstairs, the language teacher downstairs, the security guard, the gardener, the guy outside that sells cabbage and tofu.

The man says, less than a week and you’ve got your finger on the pulse of the community. Impressive.

Well, they’re neighbors, right? So did you know about this or not?

Let them call me that if they want. You do, everyone in the village does, what difference does it make?

It could make a big difference, the cousin says gravely, bro, however important this door business is, it’s not as important as people.

Go on then, what’s so important?

Cousin, Sister-in law is cheating on you!

The table where the man and the cousin sit is situated precisely on the line between light and shadow running through the McDonald’s, one half yellow, one half orange-yellow. The cousin leans into that orange-yellow half there, his wide eyes reaching over here to the yellow side, looking for the emotions on the man’s face, waiting for a righteous bandit from Outlaws of the Marsh to leap from the “I’m lovin’ it” McDonald’s, rush home, sword in hand, to start killing. The man takes a sip of lemon soda, puts it down, and says to the cousin, I know.

Huh? You know? But, but… they’re all laughing at you!

How about this, the man says, pressing the cousin back into his chair, let me tell you a story.

The lady of the house where they’re installing the gate is not a mistress, and the businessman who bought the villa isn’t having an affair. A long time ago, the businessman’s wife died. The first time the man installed a door for the businessman was just after she died. She’d fallen down a staircase in another villa, and landed on the threshold, crumpled like a burlap sack. He was installing the door on the spot where she had breathed her last breath. As he was putting it in, there was a steady stream of guests coming to offer condolences, and the businessman’s tears for his wife would break your heart. At the same time, though, he yielded to the flirtatious glances, the beauties stealthily clasping this golden opportunity to their bosoms. So as the guests went out the door, delighted with his misfortune, they would sigh, that old letch, there’s no stopping him. It was then that the businessman explained to the man, as Mencius says, one who loves others will always be loved. These ‘others’ could be anybody – your wife, other women, as long as you love someone, other people will think you don’t have big ambitions, you don’t have it all planned out, and they’ll love you.

The man asks the cousin, do you understand?

The cousin shakes his head. The man says, okay, here’s a second story.

That courtyard house in the village originally belonged to the man’s great uncle. Whenever people talk about the great uncle, they say he was mad. Back then, in the courtyard, there was a hanging flower gate. At some point, the great uncle became obsessed with this gate. The roof leaks weren’t fixed, the covered walkway sagged and wasn’t repaired, the rents went uncollected, and the family’s expenses got out of hand. The women and children suffered the most. Every time they so much as brushed against the increasingly delicate hanging flower gate, the great uncle would beat them and shout at them. Finally one day, the villagers came into their landlord’s courtyard brandishing tools, and saw the pitiful state of the house, the cowering women and children, the senseless old man, and the exquisite hanging flower gate. They set about with hoes and spades, and removed the hanging flower gate. That done, the crowd dispersed without violence.

The man asks the cousin, now do you understand?

The cousin shakes his head again.

In the third story, the man crosses the water and comes to the city. As expected, he marries the woman, and gets a job with the Water Resources Management Agency. Every year he waits for the rainy season, when he monitors the water levels along the shores of the river. But the man cannot forget that hanging flower gate, cannot forget the hanging flower gate that was taken away from its rightful place on the opposite bank of the river. From the darkness, the hanging flower gate calls to the man every night. So, one day when the man, standing in front of the bedroom wardrobe, sees another man’s eyes facing him through the half-pane of frosted glass, he decides to quit his job, and open a shop in Furniture City selling doors. He’s helped everyone in the complex in some way. The man loves doors, understands doors, anybody needing a new door can go to the man and pick one. He’d even helped liaise with the factory for the main gate of the complex, and got a discount for the Homeowner’s Committee. Behind the man’s back, everyone in the complex sighs, ah, the poor man, what a meek, naive man. But they know nothing of that hanging flower gate.

Still don’t understand? the man asks.

No.

If you don’t get it, you never will. The man waves his hand, you can go back now.

Go back? Go back where?

Go back home, the man says, I can’t give you that house.

But why, bro!

Because I want to go back there, the man says, prying open the cousin’s death grip on his sleeve. Because I want to change my registered address, I want to live in that house. I want to fix everything inside it, and I want to restore the hanging flower gate.

The man closes his eyes, and tears swirl behind his eyelids. Ah, hanging flower gate, the eternal hanging flower gate, that has been secretly snaking its roots into his imagination since he was a child. The door to happiness, beckoning to the man since childhood. He’s been crying over that door in his dreams. It was the light of happiness that would appear whenever he closed his eyes, and was never far away. Its tiles wrap around his heart. In his dark dreams, the woman comes out of the hanging flower gate, walks straight to the ferry pier, throws herself into the river, dies, becomes a corpse floating on the churning flood; his former boss at the Agency also comes out of the hanging flower gate, dies; as for his parents, they have long ago been buried where the waters will never reach, high on the mountain. He never worries about them. The only light is the glistening of the pearly tiles and shingles of the gate. Loving people may fill one’s life with meaning, but the man only loves doors. When one returns to an era that has been destroyed and locked away, and rebuilds a hanging flower gate, everything back in the world is meaningless again.

The woman twirls the key, and pops it on the coffee table in front of the man. The tea in the cup ripples, splashes out a dark yellow stain. The woman says, absent-mindedly, here’s the key.

What key?

New house, new door key.

The man quickly stands up, says, you’ve installed the door?

Yes. Not just the main door, the bedroom door, kitchen door, and dining room door. They’re all done. I didn’t skimp, they’re high-quality doors. The woman pauses, then says, you’re welcome.

We’d agreed I would install the doors, the man protests.

I remember warning you, if you didn’t decide in three days, I would, the woman says.

Along with the key, the woman gives the man a sheaf of papers.

Don’t forget, the woman says solemnly, we agreed, once the new house is done, we divorce. You get the new house, I get the old house. If you thought you could put off the divorce by dragging out this business with the doors, that didn’t work.

The man has another dream, in which he sees himself returning on the White Rhino Ferry in the middle of the night, by himself. The old house behind the pier looks just like it did when it was built a hundred years ago. The grey-green bricks are all in place, the roof tiles perfectly lined up. Between the outer and the inner courtyards, there is just the right space for the man to build his beloved hanging flower gate. The hanging flower gate he builds is exactly like the one in the magazine. It’s supposedly part of some Qing dynasty nobleman’s official residence. From either side of the hanging flower gate, the man builds two covered walkways around the courtyard, and within their embrace, yet more corridors divided by brick walls. Corridor after corridor, like intestines filling the inner courtyard, until finally it is a labyrinth, a labyrinth of profound and incomparable melancholy. As the man puts down his tile cutter, and wipes the last brick, he stands up in the center of the labyrinth.

The man is woken by a phone ringing. Again and again it rings, without stopping. The man picks it up, and hears the voice of the cousin, calmly and with controlled anger, saying cousin, come home now.

What for? You just woke me up, and in a little while I have to go install a door for someone.

Forget the door already! Come home and see what’s happened! Now!

The man hurries back to the complex, and finds the cousin fuming with anger, hands on his hips, standing in the bathroom doorway. In the bathroom, the woman is kneeling on the floor, hands tied behind her with a bedsheet, a grey rag tied between her teeth, her face pressed against the wet sink, forced to stare back at the cousin and the man. A young man, similarly bound, is squeezed into the small space on the other side of the woman. He is wearing a white basketball jersey with “Software Institute” and the number 16 on it. He hasn’t had time to put anything else on. He kneels with his legs pressed together, leaning forward as far as he can, to hide his face. The man thinks, so this is that white butterfly, who flew through one door, another door, always flying to his house, he’s finally seen him today.

The cousin picks up the mop handle and hands it to the man. The cousin says, you sort them out, bro.

The man doesn’t take the handle. The man asks, what have you done?

What have I done? I catch them for you like this, and you still ask what have I done? While speaking, the cousin gives each of them a thump on the back, bringing forth muffled groans. Before the third blow can land, the man stops the cousin and takes the mop. The man says, don’t hit people, don’t hit people.

The cousin snorts, and says, bro, I’m helping you.

You’re helping me by hitting people?

The cousin throws his head back in anger. The cousin says, when I came back, they hadn’t shut the curtains. They were in the bedroom. All the neighbors were down there, watching, pointing. When I got there, they pulled me over and made me look. What should I have done, huh? Politely knocked on the door, politely asked everyone to move along? I’m the only family you’ve got in this building.

The man says nothing.

The cousin picks up the tossed-aside mop handle, and makes to hand it to the man again. The cousin says, bro, you do the beating. Beat her once, a woman will be good, she’ll remember it for a long time. If she doesn’t obey, beat her harder. Beat her till she obeys, and she’ll be a good woman. Sister-in-law, don’t blame my brother for beating you. When a person makes a mistake, they need a beating. People are like animals, they’ll remember a beating more than a feeding. Sweet fancy words are no use, you just have to beat them hard on the back…

The man says, cousin, we’re divorced.

What?

I said, your sister-in-law and I have divorced. She isn’t your sister-in-law any more. We agreed that once the new house was fixed up, we’d split. She finished the house the day before yesterday.

Huh?

I’ll give you back the house-warming money in a bit. We were never going to have a house-moving banquet, it was agreed from the start: I would move, and then we divorce. But right now, let’s let these people go.

The man reaches out to untie the woman, and then the cousin catches on and does the same for the young man. When the rag is taken from the woman’s mouth, with a cutting stare at the cousin, she spits out a mouthful of germs and filth with a ‘pah’. The young man is a fast runner, scurrying shamefaced to the bedroom to put on his shorts, then racing shamefaced out of the building. The woman calmly and unhurriedly walks to the bedroom, and closes the door with a click.

The man takes the cousin to Nine Dragons Shoal. At Nine Dragons Shoal the river runs wide; according to legend there’s a sandbank where nine dragons played together. Excessive and persistent sand mining has made the water muddy, but sometimes you can still see a few fat river fish. At the other end of the channel is the White Rhino Ferry. Legend has it that during a major flood, a white rhino rose up from where the ferry pier is now, and helped people caught in the flood get to safety on rooftops or trees. This incident is recorded in the man’s family history, and it is said that those who survived went on to prosper. Sure enough, the population grew, and the incense has burned continuously since then. But now the solitary man, watching on his own as the water level slowly rises with the summer floods, wonders whether a white rhino will once again come to carry him. Pull him to some high place, that he, alas, cannot find by himself.

The man says to the cousin, go back, when you get married, come and tell me.

Bro?

Hurry up and get on the boat, you don’t want to wait for the next one. When you get back, remember to take good care of that house. The lower bricks are all original, good stuff. The whole thing’s almost a hundred years old.

You’re giving me the house?

The haze of sadness that has dogged the cousin the whole way is gone. He’s in his twenties and he’s strong as an ox, but he can’t help wanting to hug the man. The cousin keeps turning back to say goodbye. The cousin says, bro, I’m going now. The man waves. The cousin says, bro, I’m really going! The man is still waving. The cousin stands on the deck, holding the handrail, waving with all his might at the man, and suddenly a swell lurches him, even the arc of his waving hand is sent off course. Like the rumble of the engine, the silhouette of the cousin’s hand gets farther and farther away, until it’s finally swallowed up in the vastness of the endless water. The man, rubbing the key in his pocket, walks back to his new home.

That night, the man starts to build a hanging flower gate. A hanging flower gate is of course a secret door, a door to a box, two doors hiding each other. For the man, this is a door to happiness that has been coyly eluding him since he was little. Once he grasped this, was there anywhere he couldn’t build a hanging flower gate? The man brings some precut timber, bricks, tiles, and mortar from the shop, and completely demolishes the front door and entrance hall of the new house. Late into the night, in the front of the house, the man erects a deep red outer door, and just inside from it, a light green painted inner door. Between the pillars of the two doors, the man uses red bricks and mortar to make two walls facing each other, seamless and straight. As the walls get higher and the air gets thinner, the man feels like he’s going back to that huge inner courtyard. It’s a proper, peerlessly classic, Qing dynasty hanging flower gate. With the addition of some glazed roof tiles, the whole gate appears even more extravagant. A prayer in the dark night for prosperity and wealth, happiness and health. And the man builds wall after wall within the inner courtyard. As the last trowelful of mortar is spread, the countless walls glow with an impenetrable light. Now, he is finally in the very center of the labyrinth, where the hanging flower gate guards its innermost secret. In that thin, wan atmosphere, the man is drowning like a fish. And by drowning, he finally passes through the longed-for door of his own creation.

Comments

Chinese: https://m.douban.com/note/826901738/

Justin, July 1, 2024, 2:24p.m.