Welcome back to the Cold Window Newsletter! It’s time to get back to my initial mission with this newsletter: calling attention to great new literary writing from China. Over the last few months, I’ve sampled nearly every new Chinese short-story collection that’s come out this year. I want to tell you tell you about my favorites.

This was one of the most rewarding projects I've ever undertaken for this newsletter. As always, you can visit the newsletter on Substack to subscribe for updates and browse the archives.

Special: In search of the best new fiction in China

As of this summer, Chinese literary fiction is in a bit of a tough spot. Inside the country, there’s undeniable suspicion of literary writing affiliated with the cultural establishment: it is not a compliment to call someone 体制内, “inside the system.” A recent plagiarism scandal implicating many young establishment authors, and the schadenfreude with which their downfall was greeted on the Chinese internet, made this distrust abundantly clear. Outside of China, translators are working as tirelessly as ever to bring worthwhile stories out into the world, but there are still far too few young Chinese writers who get any sort of attention abroad (although I do think this tide is beginning to turn).

That’s why I decided to try reading everything newly published in China this year. This project was intended to be a pulse-check, an attempt to investigate in good faith the throwaway complaint that you see from Chinese readers online all the time: there’s no good literature in China anymore.

This month’s newsletter brought to you by: libraries and bookmarks.

Surprise: that complaint is wrong. The five books below are some of the best I have ever read in Chinese. They’re mostly by women. They’re all by writers born after 1980. And, to a greater and greater extent as you move up my ranking, they all poke at the boundaries of today’s urban, technologized, hyper-globalized society, until it’s hard to tell what’s fantasy and what’s reality. That’s the kind of story that makes Chinese fiction worth reading right now. And it’s the kind that can only be written by young authors.

Let’s get into it.

Some stray thoughts on this project as a whole

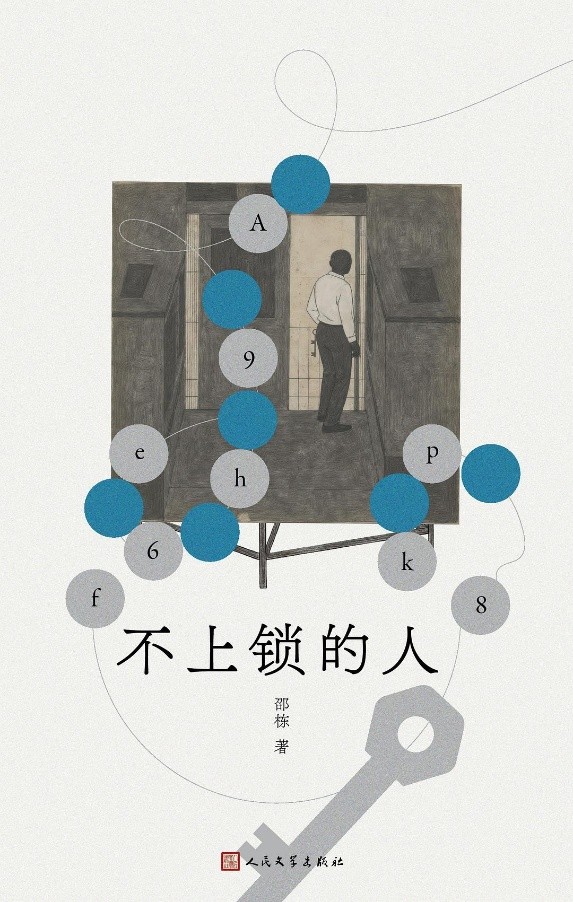

5. 邵栋《不上锁的人》(Those Who Leave the Door Unlocked by Shao Dong)

This entry is the odd one out on my list. I’d never heard of the author until he was nominated for the Blancpain-Imaginist Prize 宝珀理想国文学奖 earlier this month; he’s a bit younger than the other writers below, the only man of the bunch, and, judging by the pieces I read, the one who’s most grounded in realistic stories about traditional life. He won me over with the story 《文康乐舞》 “Recreational Dancing.” Its protagonist is a young female documentary student from Hong Kong poking around Fujian for material, and something about her voice as a narrator, both savvy and genuinely curious, made her feel like a real person in a way that not all literary narrators do. The nauseating, heartbreaking evocation of her father’s death during pandemic quarantine kicks the story into a darker mode and proves that the author has real range. I don’t think he’ll win the Blancpain prize, but he’s got me in his corner.

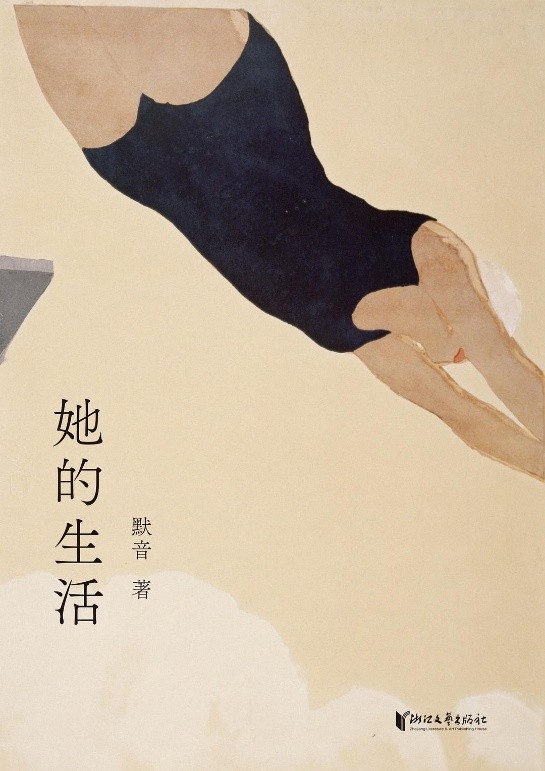

4. 默音《她的生活》(Her Life by Mo Yin)

I’ve always been curious about Mo Yin. I like that she translates novels from Japanese, including one by Yoko Tawada (Memoirs of a Polar Bear) that has gotten a lot of acclaim in China this year. I like that she has a reputation for mixing genre elements into literary writing. I like that this Reddit user went to the effort of making a (really good!) guide to her work, even though nary a word of her fiction has ever been translated into English so far. Sounds like something I would do...

《她的生活》 Her Life seems to have flown mostly under the radar within China, a small flourish between her better-selling novels and translations, but it proves that everything I’d heard about her writing is true. Consider the novella 《梦城》 “City of Dreams,” a sci-fi take on Hollywood set in future Japan. Through the eyes of a TV producer navigating corporate interests and cast-member intrigue, we explore a sci-fi world that feels upsettingly familiar: climate crisis, celebrity deepfakes, portable VR technology (“dreamvision”) that encourages you to isolate yourself from the world. I only learned later that Mount Fuji Diary, the book being adapted for dreamvision throughout the novella, is a real diary by Takeda Yuriko that was translated into Chinese by Mo Yin herself. The density of the ideas and references that Mo Yin plays with here is astounding.

3. 郭爽《肯定的火》 (Undeniable Fire by Guo Shuang)

I only read one of the three long pieces in this book, but it immediately made me want to press it into a new reader’s hands. The novella 《拱猪》 “Push Out the Pig” (named after a card game) is just such a perfect showcase of what new Chinese fiction is so good at: documenting the anxious disconnect between old and new, between parents who grew up in poverty and their children who grew up on the internet. I don’t know if Guo Shuang is a participant in fan culture herself, but she does an admirable job portraying how absorbing, liberating, and ultimately crushing it can be for a working-class child to seek escape inside online fandom. This deserves to be one of the first books people read if they want to learn about class in contemporary China.

2. 杜梨《漪》 (The Ripple of Shattered Cuckoo by Du Li)

No, the official English title of this book does not make any sense. But it still sounds kind of good, doesn’t it?

Now we’ve arrived at the truly magical writing on my list. I predicted in my end-of-year coverage for 2024 that 杜梨 Du Li would be an author to watch this year, and I’m pleased to discover how right I was. Her writing is not easy to read, at least for a non-native speaker—it’s dense, fast-paced, and prone to unexpected leaps into hallucinatory nightmarescapes. But it’s worth the effort. There’s 《三昧真火》“True Samādhi Fire,” a novella about an amateur rapper named Najia who has to contend with unexpected fame after her verses at a local competition go viral. In mingling satire about Beijing youth culture with a gradual excavation of the troubled life Najia left behind in her home province, the novella manages simultaneously to be silly, contemplative, learned, and very dark.

And then there’s 《鹃漪》 “The Cuckoo Vanishes,” Du Li at her unsettling best. A young couple moves into an apartment known for uncanny occurrences—and, as in any good haunted-house story, it’s less the apartment that turns out to be haunted than the occupants themselves. At every turn I found myself thinking back to 《竹峰寺》 “Zhufeng Temple” by 陈春成 Chen Chuncheng, one of my favorite short stories of all time. Both stories use the collision of traditional culture with the present as the root of a mystery story—in “Zhufeng Temple,” it’s a legendary stone stele that has gone missing; in “The Cuckoo Vanishes,” it’s a Ming-dynasty text linked to women disappearing into their dreams. The difference is that Du Li, unlike Chen Chuncheng, likes to dive deep into the haunting nonsense aesthetics of a nightmare. The worlds she describes are disturbing—both the dream world, and the real world that it masks.

1. 张天翼《人鱼之间》 (Beyond Truth and Tales by Zhang Tianyi)

One thing that this project has taught me is that I like fiction that overflows with ideas. If an author has a capacious enough brain to come up with ten wildly different storylines and figure out how to weave them together, I don’t want her to cut a single one out. Give me writing like a rainforest: bursting with so many sights and sounds that I can’t take it in all at once, but still somehow forming a single dense, fecund ecosystem.

That describes all the books on this list to a greater or lesser extent, but none more than 《人鱼之间》 Beyond Truth and Tales. 张天翼 Zhang Tianyi takes the elements of the other books I liked and dials them up to eleven. Allusions to classic texts? The whole book is structured around postmodern deconstructions of myths and fairy tales. (I’m reminded of Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber, one of my favorite books and a sort of spiritual cousin to Beyond Truth and Tales.) Speculative elements reflecting the excesses of real-world pop culture? This is the only book on my list where you will find a candy-colored parody of Hogwarts where students wear skinsuits to look like their favorite celebrities. (See 《豆茎》 “The Beanstalk,” the collection’s closer.)

Most of all, Beyond Truth and Tales is just fun to read. Like Du Li, Zhang Tianyi knows how to make a silly moment deadly serious—and more importantly, she knows how to pull a deeply upsetting plot out of a tailspin and give you permission to laugh. I couldn’t help getting deeply attached to the awkward, endearing protagonists of 《雕像》 “The Statue” (a classical-art-themed romance)! And at the end of “The Beanstalk,” when it finally clicks into place how the story’s various threads link to each other—reader, I gasped aloud.

Zhang Tianyi is already a celebrity for her prior collection, 《如雪如山》 Like the Snow, Like the Mountains, which is among the most influential works of Chinese fiction from the last five years. If her writing stays this good, then we’re going to be reading her for a long, long time.

That’s it for this issue. If there’s more good fiction you think I missed, let me know. Look forward to a shorter, more personal interim post on Substack in the near term, and another full issue cross-posted in this space next month. Thanks for reading.

Comments

Dear Mr. Rule,Hi Andrew

I'm an admirer of Paper Republic's work bridging literary cultures. I've just completed a series of four novels (QiFu Horizons, etc.) that explore Eastern archetypes within original sci-fi/fantasy, a mission parallel to your own. I've made them freely available online. As an expert in the space, I thought the project might be of personal interest. Link: https://koru-imprint.com

Mickey Waitoa, September 28, 2025, 4:23a.m.