Welcome back to the Cold Window Newsletter! In this issue: a first foray into the world of Chinese internet literature, kicking off a column that will be running through several issues of this newsletter throughout 2025; and short fiction from the margins of southern China.

A note on numbering: this is the third issue of the newsletter published on Paper Republic, but it is the sixth full-length issue overall. I’ve also begun writing shorter features between main issues that will not be cross-posted here, so if you want to receive the interim feature that will be coming out later this month, make sure to visit the newsletter’s main page on Substack.

Guide: Thirteen ways of looking at Chinese internet literature (1-2)

When we write about Chinese fiction in English, we have a tendency to draw a clear line between translated literary fiction (serious, challenging, widely acclaimed but little read) and translated popular fiction (addictive, commercial, devoured in private by millions but rarely acknowledged by the literary establishment). Despite the warmth and open-mindedness of readers on the literary fiction side, and despite the explosive growth of translation websites and fan communities on the popular fiction side, this divide has persisted. But, in my view, as long as you’re only reading work from one side of the divide, you’re missing out on a huge swath of the creativity, diversity, and insight that Chinese fiction can offer.

I’m no expert in Chinese internet fiction. There are tens of millions of fans out there who are more qualified than me, by virtue of their reading habits, to tell you about the vast world of popular serialized fiction hosted on Chinese websites like Qidian 起点 and disseminated to a colossal international fanbase by legions of professional and amateur translators. Compared with them, I’ve only dipped my toe in these waters, and I’m going to rely on more experienced readers to correct me if I get anything wrong.

But given the goal of this entire newsletter—to bring attention to areas of the Chinese literary landscape that English-language readers are otherwise unaware of—I think it’s essential that I try to convey a sense of the breadth and quality of Chinese internet literature, beyond the tiny sliver of it that has already attracted mainstream attention in the West. That’s the idea behind this column, which will run on and off through the next several issues of this newsletter. I’ll offer 13 ways of looking at internet fiction to help you approach it for the first time if you’re new to this world, or re-approach it if you’re already an established fan. If all goes to plan, I’ll cover a lot of ground, but for today, let’s start with the basics. How should we view Chinese internet fiction in the context of its growing popularity in the English-speaking world?

Way #1: as an international publishing phenomenon

Probably more than any other author, Mo Xiang Tong Xiu 墨香铜臭 is responsible for English-language readers waking up to the existence of Chinese internet fiction. I can’t be the only one who was caught off-guard when English translations of three novels by the pseudonymous author (known as MXTX to her Western fans) burst onto the New York Times bestseller list simultaneously in 2021. For translated Chinese novels to meet such immediate commercial success is nearly unheard-of in the West, let alone from a publisher that had never come out with a translated Chinese book before (Seven Seas Entertainment) and a group of translators identified only by their web handles (Suika, Pengie, Faelicy, and Lily).

The first English volumes of three danmei novels by Mo Xiang Tong Xiu 墨香铜臭, all released by Seven Seas Entertainment in 2021: Heaven Official’s Blessing《天官赐福》, Grandmaster of Demonic Cultivation 《魔道祖师》, and The Scum Villain’s Self-Saving System《人渣反派自救系统》

Of course, the rise of MXTX in the West didn’t really come out of nowhere. By 2021, print versions of online novels had already been reliable sellers in Chinese bookstores for years, and translated editions had been a major force in Southeast Asian book markets for nearly a decade. Manhua (comic) adaptations, ubiquitous TV shows like The Untamed 《陈情令》, and a whole ecosystem of fan and licensed translation platforms lay the foundation for the success of these print novels in English. (More on these translation sites in a future installment.) But for me, and surely many other English-language readers who were used to interacting with Chinese fiction primarily via highbrow literary novels, it certainly felt like MXTX’s success came out of nowhere. This was the moment we realized we hadn’t been paying attention, and we needed to start.

Still, in the years since, critics, publishers, and literary translators seem to have been slow to adapt to the newly dominant role of internet novels in the translated Chinese fiction market. Maybe this is because they’re uncomfortable or unfamiliar with danmei, the genre of non-explicit gay male romance (written for an overwhelmingly female audience) to which nearly every single one of the new translated bestsellers belongs. Maybe it’s because these novels demand a different rights acquisition process than traditional books, or because they’re simply too long to easily fit traditional publishing deals and rhythms. (The English version of Heaven Official’s Blessing 《天官赐福》, MXTX’s defining work, runs to 8 print volumes of 400 pages each.) Maybe it’s because traditional publishers and critics simply don’t think they’re good literature. (I obviously disagree, or we wouldn’t be here!)

Regardless, wholly unconcerned with the literary establishment’s foot-dragging, translated internet novels have continued to pour out of small publishing houses and into the eager hands of readers. A project by blackbirdsye documents the dozens of danmei novels that have already been released or announced in English, either in paperback, hardcover, or ebook forms. And I’ve met countless people in their teens and twenties who are huge fans of danmei novels in English, including some who had no interest in China or its literature before.

I’m starting this column with MXTX partly because her success was a wake-up call for the English-speaking world about the importance of Chinese internet literature. Even more than that, though, I’m starting with her because I want to emphasize that Heaven Official’s Blessing and other blockbuster print translations of danmei novels, while important, are just the tip of the internet literature iceberg. For all the millions of copies that these novels are selling in the United States, they only provide the barest glimpse of the quantity—and quality!—of translated webnovels being read every day on the English-language Internet, largely by readers who have utterly no contact with Chinese fiction released through traditional publishing channels. The universe of internet fiction that has not been translated yet is even more vast, even more impossible to map. But I still want to try. Let it not be said that the Cold Window Newsletter shies away from a challenge.

Way #2: as an object of Western scrutiny

In future installments of this column, I’ll dive deeper into parts of the Chinese internet literature scene that are rarely written about in English, especially in mainstream, non-specialist, beginner-friendly sources. But for now, just to tide you over, I’ll point you toward some of the few widely available resources in English that I think have done a good job introducing internet literature to readers who might know a lot about Chinese literary fiction but relatively little about its online counterpart.

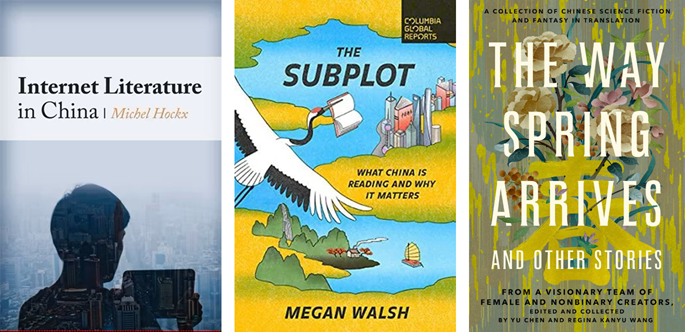

Internet Literature in China by Michel Hockx (2015); The Subplot: What China Is Reading and Why It Matters by Megan Walsh (2022); and The Way Spring Arrives: A Collection of Chinese Science Fiction and Fantasy in Translation, edited by Yu Chen and Regina Kanyu Wang (2022)

On the more academic side, but still very readable, is Michel Hockx’s Internet Literature in China, published in 2015 by Columbia University Press. Hockx must be one of the few scholars writing in English today who was actively following early Internet literature forums like Under the Banyan Tree 榕树下 during their first heyday in the early 2000s. While his book skews a bit more toward avant-garde online literary experiments than the mass-market webnovels that average people actually read, it provides a very insightful look into how the internet literature ecosystem integrated itself, and resisted against, existing systems of publishing, prestige, and censorship. What holds the book back, unfortunately, is its age. To a substantial extent, the internet on which contemporary webnovels grow is no longer the same one that Hockx was writing about a decade ago, in terms of both commercial structures and increasing efforts by the government to control or ban undesirable online content. Many parts of Hockx’s book already feel like ancient history, not least his prediction that internet fiction may already have passed its peak.

You’ll get a more up-to-date overview from Megan Walsh’s chapter on “The Factory: The Business of Online Escapism” in her excellent 2022 book The Subplot: What China Is Reading and Why It Matters. The chapter is brief, but it’s the best English source I’ve found to explain the factory-line-style production that defines so much of the Chinese internet literature industry. Walsh walks you through the defining clichés of the novels that emerge from this factory line: toxic, individualistic, shamelessly ambitious antiheroes in “male-channel” (男频) fiction; idealized, feisty, exploited female romantic leads in “female-channel” (女频) fiction; and game-inspired level-up systems for the protagonists to work through, lending an illusion of progress to serialized narratives that often run to thousands of chapters. There’s a fundamental contradiction between the government’s efforts to control online narratives and the platforms’ race to make their content as addictive and commercially appealing as possible. Walsh excels at picking this contradiction apart.

Both Hockx and Walsh have one more small shortcoming, which is that they seem simply not to like reading popular internet novels that much. Which is fair! But to get a real sense for the subversive and creative potential of internet literature, you need to seek out a scholar who’s also a fan. To me, Xueting Christine Ni fits that bill. (You may know her from her translated anthology Sinophagia: A Celebration of Chinese Horror, which I raved about on this newsletter last year.) If you haven’t yet read the 2022 sci-fi/fantasy anthology The Way Spring Arrives and Other Stories, you really should, not least because it contains an essential essay by Ni entitled “Net Novels and the ‘She Era’: How Internet Novels Opened the Door for Female Readers and Writers in China.” Alongside a very useful history of writing by and for women on the Chinese internet, Ni’s essay points out all the ways that internet fiction has allowed web users to challenge misogyny, stereotypes, and sexual taboos, carving out a space for feminist self-expression in the midst of commercialization and censorship. Out of the three pieces I’ve recommended here, this is the only one that will make you excited to go read Chinese internet literature for yourself. Which makes it the most useful source of all.

I’ll be back with more ways of looking at internet literature next month. But for now, it’s time to wander out of the realm of the web and back into the realm of literary fiction, where I have two writers from the “post-80s” generation that I’ve been itching to recommend.

Feature: Small-town family dramas from the margins of southern China

When it comes to contemporary Chinese literature, “the South” might be too diffuse of a concept to be especially useful. Among scholars who study new Chinese fiction, the term “New South Writing” 新南方写作 is already starting to splinter into smaller categories that reflect the vast thematic and stylistic diversity of writing from the country’s southern provinces. Hence articles heralding the rise of the “New Shanghai” (新上海), “New Zhejiang” (新浙派), and, most recently, “New Southeast” (新西南) literary movements. Hopefully these new divisions will help highlight writing from regions and communities that have historically existed on the far margins of Chinese fiction. I want to share with you two writers who hail from these margins, each of whom has a gift for examining the tragedies and cruelties of life far from the centers of power.

《唯水年轻》 (Only the Sea Is Young, 2024)

The first is Lin Sen, born 1982, who has made a career out of crisp, powerful stories about rural life in the tropical island province of Hainan. He’s probably best known for his sea stories, especially 《海里岸上》 “On Land, At Sea” , the first in a trilogy of seafaring novellas that were recently collected under the title 《唯水年轻》Only the Sea Is Young. Marketed (somewhat uncreatively) as “China’s The Old Man and the Sea,” the novella revolves around, yes, an elderly fisherman watching the seafaring traditions of his youth become subsumed by technology and commercialism, all against a backdrop of environmental crisis and territorial disputes in the South China Sea.

Rather than the sea stories, though, my recommended Lin Sen starting point is set in the forests of inland Hainan. 《抬木人》 “The Woodsmen” is a darkly funny story about a pair of rough, desperate, soul-deadened brothers who make a living poaching trees from the woods and hauling them to market for petty cash. There’s a hint of Lu Xun in Lin’s ironic tone as he depicts the brothers reveling in useless cruelty toward the townspeople, their aging father, and each other. But, more than in Lu Xun’s satires, there is a deep well of pathos underlying the buffoonish woodsmen, because it is clear that their aggression stems from a feeling of bewilderment at the loss of their mother, an unwilling bride purchased from Vietnam, and shame at the undeniable failures that they’ve made of their lives. If all this sounds too heavy for you, you can turn instead to “To Longtang with a Bamboo Sword” 《背上竹剑去龙塘》, another excellent landbound story (with a martial arts motif!) that Jim Weldon translated for Pathlight magazine a few years ago.

If you do give “The Woodsmen” a try, you’ll be able to savor its surprising resonances with another recent story from the margins of the South, 《集美饭店》 “Jimei Hotel,” by the Guizhou-based author Li Chao 李晁. Like Lin Sen, Li (born 1986) likes to set his stories against the backdrop of stifling small-town society in southern China. Unlike Lin, though, Li is a slow, imagistic writer, as reflected in the title of the collection where “Jimei Hotel” appears, 《雾中河》 River in the Fog.

《雾中河》(River in the Fog, 2020)

Not much happens in “Jimei Hotel”: a young woman returns to her hometown in the wake of an unspecified failure in the big city and debates with her aunt about whether to reopen her late father’s failed hotel in the middle of town. The art of the story lies in its patient depiction of relationships. Like in “The Woodsmen,” interactions between adult siblings lie at the center of “Jimei Hotel,” as do the wounds left behind by an absent mother and a bullying, ineffectual father. But whereas Lin Sen mines these relationships for irony, Li Chao uses them to gradually flesh out the protagonist’s feelings about the small town she’d intended to leave behind.

That’s all for this issue. Keep an eye out for a shorter Substack-only installment in the next few weeks about a recent scandal surrounding another young Southern writer. Then, in the next full issue: a closer look at the dizzying diversity of internet literature genres, and a round-up of some notable fiction collections from the first half of 2025. Thanks for reading!

Comments

There are no comments yet.