Welcome back to the Cold Window Newsletter! In this issue, the long-delayed return to my series on Chinese internet literature, with a focus on the chaotic sprawl of genres within which online fiction is produced. There’s a lot to say. No author profiles or recommended stories this time, but look forward to a bunch of those in a seasonal special later this summer.

I made this disclaimer last time, but it bears repeating: Chinese internet literature is one of the most massive media ecosystems in the world, and I am as far as can be from an expert. If you, like me, are a newcomer in this world, let’s treat this series as an opportunity to learn about it together. And if you’re a long-standing fan, I hope you’ll lend your expertise to the conversation. As always, for more and to subscribe, feel free to visit the newsletter on Substack, where this article was first posted in two parts earlier this month.

Thirteen ways of looking at Chinese internet literature: Genre madness (#3-6)

The first Chinese internet novel I ever really got into was about video gamers in a post-apocalyptic world. A game-master transports them into the wasteland under the pretense that they are playing a VR game, and by manipulating them with quests, meaningless digital currencies, and promises of exclusive rewards, he manages to build an unstoppable army of blithe gamer warriors willing to carry out his every whim. I was astonished by the creativity of the concept: its humor, its moral ambiguity, its blending of classic sci-fi with manga tropes and game mechanics... It wasn’t until hundreds of chapters in that I discovered that this exact blend of story elements has a name: “Fourth Calamity” 第四天灾 fiction, so called because the arrival of gamers who fear no death and are hungry for loot on an unsuspecting world is an epoch-scale calamity. The Fourth Calamity subgenre is a tiny sliver of the video game novel subgenre, which is only part of the sci-fi and system story (系统文) genres. Novels in this subgenre operate in an incredibly specific range of plots. And yet there are a lot of them.

A tiny subset of the novels tagged “Fourth Calamity” on Qidian 起点, China’s largest internet novel platform.

Chinese internet literature is VAST. All it takes is a quick scroll through Qidian or Novel Updates to see the whole bedazzling landscape of genres and subgenres unroll before you. But you’re not likely to learn much about internet literature as a whole just by gawking at genre names. Part of my thesis in this series is that internet literature cannot be understood at a glance (it takes at least thirteen!), and that goes for internet genres as well. So, for our next four Ways of Looking, we’ll try to approach genre from a handful of different perspectives: a lexicon of how genres are talked about; a bird’s-eye view of why they matter; a basic taxonomy of their story forms; and a stroll through some of the classic genres that have led internet literature to where it is today.

Let’s get to it. Check out my post from May if you want a refresher on Ways #1 and #2.

Way #3: as a new way to talk about literary pleasure

Like any subculture, internet literature fandom has a vocabulary of its own that can be intimidating for those outside of it. Without getting into genre-specific terminology, I want to give a quick introduction to the words that fans use to talk about what they like and what they don’t. If you want to understand genre, that’s where you have to start. After all, genre itself is just a tool to tell you what pleasures to expect from a novel and how they will be delivered.

- 爽 (shuăng). Shuăng is the feeling of pleasure that you get from sliding effortlessly through a novel. You often see it described in drug terms: it’s an addictive high that wears off over time if an author doesn’t constantly come up with new ways to stimulate it. 爽点 (pleasure points) are the parts of a novel that compel you to return to it obsessively, and 爽文 (pleasure lit) is a slightly dismissive term for novels that only exist to take you from one pleasure point to the next.

- 嗑CP (ship). A CP is a pair of preexisting characters, and for a fan to嗑 them is to ship them together. Thus is a fanfiction born. 嗑CP is one of the main ways that fans (especially female fans) engage with internet media as both readers and writers, and is therefore one of the most powerful engines of internet literature and of Chinese pop culture as a whole. More on this in a future installment.

Fanart of Tom Riddle (Voldemort 伏地魔) from Harry Potter and Lin Daiyu 林黛玉 from Dream of the Red Chamber. Together, they’re 伏黛, one of the most classic and influential ships in the history of Chinese internet literature. If that doesn’t immediately sell you on the creative power of internet literature, I don’t know why you’re even reading this newsletter. Source here.

- 男频、女频 (male-channel and female-channel). The marketing of modern internet novels is extremely gendered. Novels and even entire genres and platforms are categorized as “male-channel” and “female-channel” based on the assumed gender of their authors and audience. These terms can carry a slightly derogatory implication of pandering shallowly to male or female readers’ base desires. It’s a problematic binary, because internet novel authorship and readership are both more diverse than these terms make them seem. More on this later too.

- 穿越 (transmigration). A ubiquitous starting point in modern internet novels, both male-channel and female-channel. The protagonist suddenly wakes up in another body or on another world, typically (but not always) with memories of their prior life that will help them in their new surroundings. This is called transmigration in Chinese internet literature fandom; on the rest of the English internet it’s usually referred to with its Japanese name, isekai. In our tour through various genres next week, you’ll see that whole novels can be made out of a protagonist getting isekai’d over and over and over.

- 系统 (system). Another ubiquitous plot element across the gender spectrum. Many, many novels contain a disembodied force governing the protagonist’s progression through higher and higher power levels, telling them what to do next, and doling out rewards or punishments based on their performance, like a quest pane in a video game.

- 梗 (meme). A 梗 is not necessarily a full-fledged internet meme; it might just be a viral phrase or punchline. When a novel relies heavily on 梗s, it can be extremely difficult to translate (especially if it’s a machine doing the translating). It goes without saying that we’ll be talking about translation a whole lot later on.

The above is a starter pack of terms that apply to internet lit as a whole, but each genre also comes with its own lexicon. Fortunately, I’m standing on the shoulders of Substackers before me, several of whom have created essential guides to guide you on your wanderings through the various genres. Em over at Active Faults has for years been the authoritative source in English on the vocabulary of Chinese internet fandom, including fanfiction. And Wuxia Wanderings is helpful on the varied terminology of wuxia and xianxia, much of which comes from the pre-internet era of martial arts fiction but is still useful today. (See also: Jeremy “Deathblade” Bai’s Youtube explainers.)

Way #4: as a constant cycle of satisfaction and expectation

At first glance, the concept of genre might seem too intuitive to merit all the time I’m spending talking about it. But in a literary form as competitive, fast-moving, formulaic, and pared down as the Chinese internet novel, genre is fundamental to every aspect of how these novels are produced and consumed. I started to take genre seriously when I came across a series of lectures by the veteran web publisher and critic weid (real name 段伟 Duan Wei) in conversation with scholar Shao Yanjun 邵燕君, full transcripts of which are available online. For weid, genre is the art of constantly setting up and satisfying expectations, which each satisfaction laying the groundwork for the next, even higher satisfaction. A master of genre how to call on readers’ previous associations with other works to heighten their anticipation, and to deliver satisfaction in just surprising enough a fashion to keep them hungry for more. This cycle of anticipation, surprise, satisfaction, and more anticipation is not a bad working definition of shuăng.

Left: weid (real name Duan Wei 段伟). Right: Shao Yanjun 邵燕君.

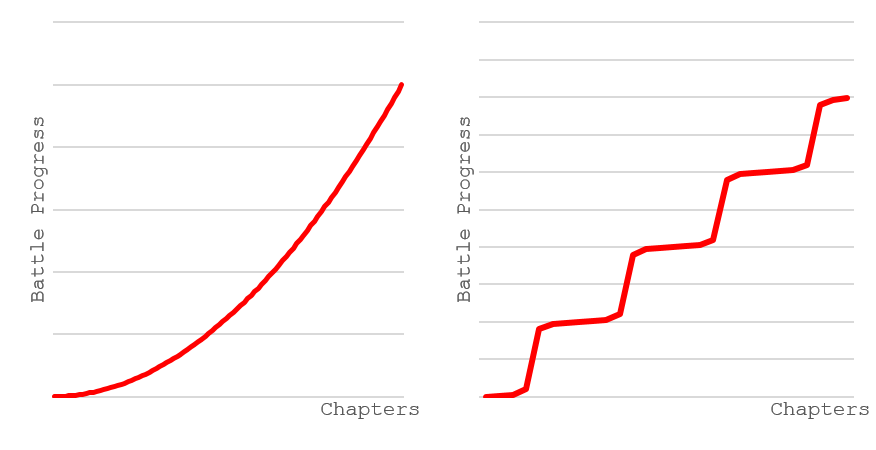

Weid’s strength as a genre commentator is that he looks at internet literature from an editor’s, not an author’s, standpoint. An author might be focused on what sets their work apart from the rest, but an editor can step back and discern how collections of unique points in individual works combine into curves that repeat again and again between stories. One of his theses is that all internet novel plots, regardless of genre, can be modeled as battles (战斗); what varies between genres are the weapons used to fight these battles and the pace at which they unfold. In a romance novel, for instance, the battle is fought with words and social politics, and an individual relationship might follow an exponential curve, at first facing seemingly impossible odds before suddenly ratcheting up to undeniable victory (below left). A plotline in a “leveling-up” story 升级文, in which the protagonist wins power and weapon upgrades video-game-style through successive campaigns, is more likely to follow a stepwise progression (below right):

Meanwhile, the basic progression of a traditional wuxia (martial arts) novel is the linear accumulation of power and abilities from start to finish (below left). And all of this differs heavily from the wavering line of traditional literary fiction (below right), with its climaxes and setbacks, which can be observed in some classic works from the early web but is greatly weakened in the current standard format of serialized, constant-satisfaction-seeking internet novels.

There’s room to criticize weid’s formulation here. His “battle progress” model of genre does not seem as well-suited to female-channel plots as male-channel ones, and it’s obvious at a glance that any story needs to borrow from all of these plot structures if it’s going to keep the reader’s attention. But what I like about his graph metaphor is how clearly it shows that the genre demands of internet literature—the need for ever more satisfying victories in each plot arc, the expectation that core genre elements will be repeated and renewed over and over again for thousands of chapters—produce a story logic that diverges from what we’re used to in traditional literature. This will be even clearer below when we look at specific genres, many of which create shuăng through looping, gamelike plots that look almost nothing like traditional literary stories.

Ultimately, I’m willing to accept weid’s basic genre formulas because of how often internet novels are able to transcend them. In their quest to produce ever better stories, authors are constantly poking and prodding at these formulas, producing moments of unexpected delight (惊喜) in which readers’ anticipation is satisfied in just a slightly different way from what genre conventions had led them to expect. Surely the reason we have so many genres is because there are as many ways of feeling satisfied and surprised within a story as there are readers. As long as readers keep demanding moments of unexpected delight out of their stories, authors will continue to innovate, and the task of tracking genres and subgenres will become ever more futile.

But let’s try anyway, shall we?

Way #5: as a taxonomy of story forms

Many discussions of internet genres, both in Chinese and English, are content to present them as lists of story types all in a row, like a menu authors choose from when they sit down to write. But if we’re going to try to understand what makes Chinese internet literature appealing, that approach feels seriously insufficient to me. Like I said above, genre is about not just the existing tropes you pull into your novel, but also the ways you satisfy and surprise your readers. Making them hungry for more, while leaving room for new combinations, new genres, to arise.

My favorite approach to genre classification comes from 王玉玊 Wang Yusu in her book 《编码新世界》 Coding a New World. Wang proposes that the most recent generation of internet literature has been heavily shaped by cross-fertilization with animation, comics, and, most of all, games. I think her taxonomy is so good that I don’t want to get in the way. Instead, I’ll just translate portions below so that she can walk you through it herself.

《编码新世界——游戏化向度的网络文学》(Coding a New World: The Gamified Turn in Internet Literature, 2021)

- Leveling-up and system stories. These stories all show the clear influence of the questing and leveling-up structures from online games. The protagonist is required to constantly accept and complete quests, receive rewards, increase in strength, and accept new quests in a cyclical process that forms the main structure of the story. In systemless leveling-up stories 升级文, the protagonist’s motivation to achieve their goal—whether it is to ascend to immortality or to conquer the earth—ultimately comes from their own desires. […] More recently, the system story 系统文 genre portrays it as thoroughly natural for protagonists to be controlled by their systems. Not only does the external system assist the protagonist in the form of money, cheat codes, etc., it also supplies the protagonist’s entire life purpose.

- Slice-of-life and pampering stories. Slice-of-life 日常向 stories pose a challenge to the traditional narrative impulse. They are no longer invested in telling complex stories featuring exposition, development, climax, and resolution. Instead, they revolve around highly aestheticized depictions of daily life. [...] Around 2013, the pampering story 甜宠文 trend rose to prominence within female-oriented internet literature, and it soon became the sole guiding model for emotional development within female-oriented novels. Strictly speaking, the intimate relationship between the male and female leads in a pampering story is not love but rather soulmateship 羁绊: as a perfect pair fated by heaven to be together, the two characters adore each other, understand each other perfectly, and trust each other unquestioningly. No third party ever butts in; no conflicts or misunderstandings ever arise.

- Infinite flow and rapid transmigration. These stories incorporate worldbuilding elements of many different genres in rapid succession. In one chapter the protagonist might be operating a mech suit in a sci-fi world, while in the next he might become entangled in a power struggle between families in a historical setting. [...] In infinite flow 无限流 stories, the logic of the original world and the parallel “copy-worlds,” particularly mystery-solving elements in decoding this logic, become a primary reason for reading the story. Why does the protagonist keep appearing in different worlds? What does the overworld actually want from him? What secrets and traps are hiding from him in the copy-worlds? [...] Rapid transmigration 快穿 is a subgenre of infinite flow oriented toward female readers. The pleasure of these stories comes primarily from the subversion of genre. In a typical rapid-transmigration story, each of the parallel worlds comes pre-loaded with the conventions and tropes of an existing internet literature genre. The protagonist forges a new path by breaking the genre rules of each successive world, all while mocking the irrationality of the original tropes.

(Let me cut in for a second to say that this Reddit post also does a fantastic job of explaining infinite flow to the uninitiated.)

《无限恐怖》(Terror Infinity by zhttty, 2007), one of the progenitors of the infinite flow 无限流 genre

Way #6: as a constantly evolving genre history

Of course, there’s a much more conventional set of genre terms that fans and platforms usually use to describe internet novels. As overlapping and vaguely-defined as they sometimes are, it’s worth taking a tour of these conventional genres, passing by some examples of influential novels in each genre along the way.

Don’t treat this as a reading list—I haven’t read most of what’s on here myself. I’ll also admit that the coverage of female-oriented fiction 女性向 below is far from complete, both because I’ve read less of it and because its historical importance is often understated in the Chinese sources I rely on for this series. So just think of this as a meandering, somewhat random stroll through genre history. (My selections are primarily informed by《网络文学经典选读》(2016), edited by 邵燕君, among other more recent sources.) Hopefully some proper reading lists, curated by myself and other fans based on what we actually love to read, will follow.

A note on links: in this and future issues, the Chinese title of each novel will lead to the original text, if an official Chinese version is still accessible on the internet (not always a sure bet). The English title will lead to the officially licensed translation if it exists, or to the fan-maintained Novel Updates page if not.

Beginnings

The actual starting point of Chinese internet literature is of some debate, but it’s generally accepted that it has roots in early experiments in serialized fiction on Taiwanese bulletin boards. 《悟空传》, a landmark Journey to the West fanfiction, is one of the earliest works that still reads like a modern internet novel.

Qihuan 奇幻

So-called “Western-style fantasy,” defined by elements like magic, orcs, dwarves, etc. This genre generated massively popular novels during the 2000s, including some some of the first internet genres to gain officially licensed translations in English. Subgenres include D&D, sword-and-sorcery, and steampunk.

Cultivation 修仙 and xianxia 仙侠

Outgrowths of older Chinese wuxia and supernatural novels, mixed with elements of Western and Japanese fantasy stories. At their core, these stories follow a protagonist training to ascend to immortality. There’s no precise boundary between the two terms, but “xianxia” is often understood to refer to cultivation stories taking place in historical or mythical Chinese settings, while “cultivation” is a broader category that could also take place in modern or science-fictional settings.

Xuanhuan 玄幻

Also called “Eastern-style fantasy” to differentiate it from qihuan. This is an extremely broad category of fantasy stories that place a heavy emphasis on original worldbuilding and creative leveling-up systems. Many infinite flow 无限流 stories fit into this category. More recently, the success of 《诡秘之主》 has sparked a trend of xuanhuan novels inspired by the Cthulhu mythos 克苏鲁.

Tomb-raiding 盗墓

Suspenseful archaeology-adventure stories borrowing heavily from traditional Chinese culture. You don’t hear too much about this genre lately, but its early classics remain some of the defining works of Chinese internet literature.

History 历史 and historical romance 古代言情

The male-oriented side of historical novels includes plenty of influential transmigration, military, and alternate history stories, but it’s the female-oriented historical romance side that is most vibrant and has had the biggest impact on pop culture. Subgenres of historical romance include palace intrigue 宫斗 and feuding family 宅斗 stories, usually starting with a transmigration. There’s also field-tilling literature 种田文, a more relaxed subgenre in which the transmigrated protagonist ekes out a life (and romance) within a traditional farming or merchant society.

Urban romance 都市言情

Romance stories that take place in modern settings, not history. In addition to the evergreen campus romance 校园言情, other subgenres like “domineering CEO” 霸总 and “high-ranking cadre” 高干 have all had their turns in the spotlight. (霸总文 are predominantly male-female stories, while 高干文 was a subgenre of mostly male-male romance that was wiped off the major novel platforms during a 2014 censorship campaign).

Danmei 耽美

Danmei, the internationally beloved genre of male-male romance stories written by and for women that I discussed at the beginning of this series, can overlap with just about any of the genres I’ve listed above. Historical transmigration, sci-fi, and infinite flow all have their own danmei canons. I’m following the example of many scholars and web literature platforms before me by giving them their own section, so as to reflect their independent development and fanbase.

That’s it for this month’s internet genre deep dive. Next time: a return to literary fiction for a special issue on the best short fiction collections of the year so far. Thanks for reading!

Comments

There are no comments yet.