Welcome back to the Cold Window Newsletter. I’ve always wished that someone would write an English guide to the best Chinese writing of the year. Now, I get to be the one to do it. Since the beginning of last year, I’ve been on a quest to read every new short fiction collection published in China in 2025. I’m finished, and I’m ready to share.

I hope to repeat this project in future years. As always, you can visit the newsletter on Substack to subscribe for updates and browse the archives.

Special: The year in new Chinese fiction

I like to focus on short stories not just because they’re an easy way for a non-native reader of Chinese to experience as many voices as possible, but also because reading short fiction is, pretty definitively, the best way to get your finger on the pulse of cutting-edge writing in China. Even more than in the Anglosphere, young Chinese writers nearly always stick to publishing short stories during the first phase of their career, slowly building up enough of a reputation to produce a full-length novel later on. Older authors write short fiction too, of course. But the best stuff consistently comes from the younger generation, because they’re the ones with the drive to experiment with form, prod the boundaries of what can be written about, and secure their place in the next incarnation of Chinese literature.

If you’re a reader of Chinese, or a translator or publisher interested in getting good stories in front of more readers, I hope the value of this list is self-apparent. But let me briefly make the case for why it’s worthwhile to pay attention to Chinese fiction even if you don’t usually keep up with contemporary literature. Chinese intellectual culture is driven by a vast, cosmopolitan, mostly urban, mostly young community of readers, writers, and artists. They have strong opinions about the state of Chinese society and the world, and they’ll always express those opinions, heedless of efforts to rein them in. The Douban lists I analyzed recently are one reflection—skewed and oblique though it may be—of how Chinese intellectuals view the world. But their worldview is expressed much more directly through stories. All that’s left is for us to listen.

I maxed out my library card for this post. Didn’t even know I could do that.

My takeaways from a year of reading

(See the bottom of the post for the rules of this reading project.)

Below are my top five picks from the second half of the year, followed by an overall list of the ten best collections of 2025. You can find my summer analysis of fiction from the first half of 2025 here.

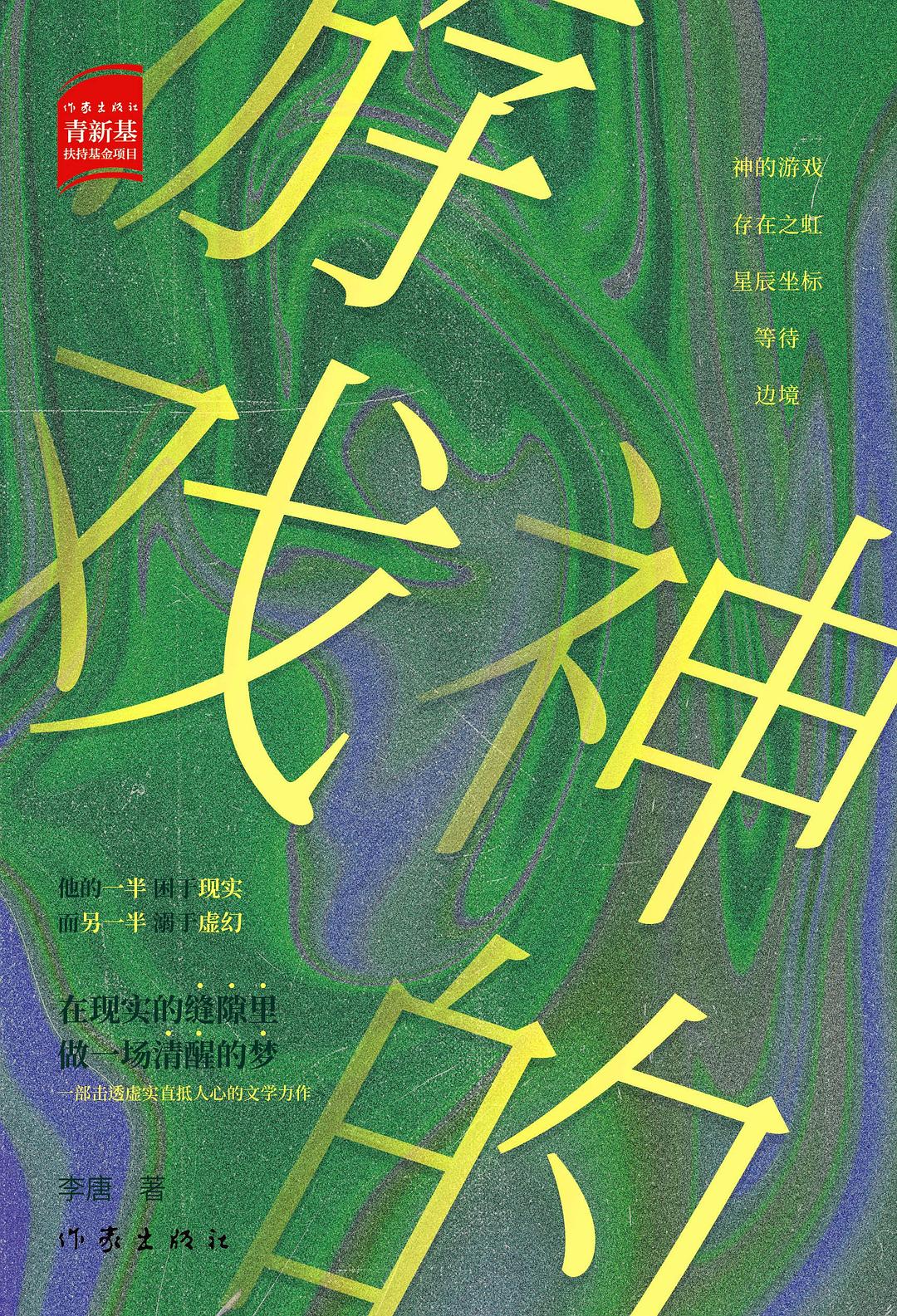

5. 李唐《神的游戏》 (Godly Games by Li Tang)

Li Tang is a cerebral writer, with a love of carefully composed, somewhat aloof plots and a self-acknowledged debt to Bolaño—but none of this is particularly uncommon on the Chinese fiction circuit these days. What sets Li apart for me, particularly in his newest collection, is how fluid and welcoming his language is, approachable enough that even a less-than-confident reader of Chinese will feel propelled toward the final page. The collection moves from more grounded stories in its first half toward gradually more imaginative and fantastical pieces in the second. Thanks to that welcoming writing style, even a more out-there piece like 《等待》“Waiting” (about a lonely young man from a broken home who develops an obsession with aliens) feels emotionally accessible and lighter than air.

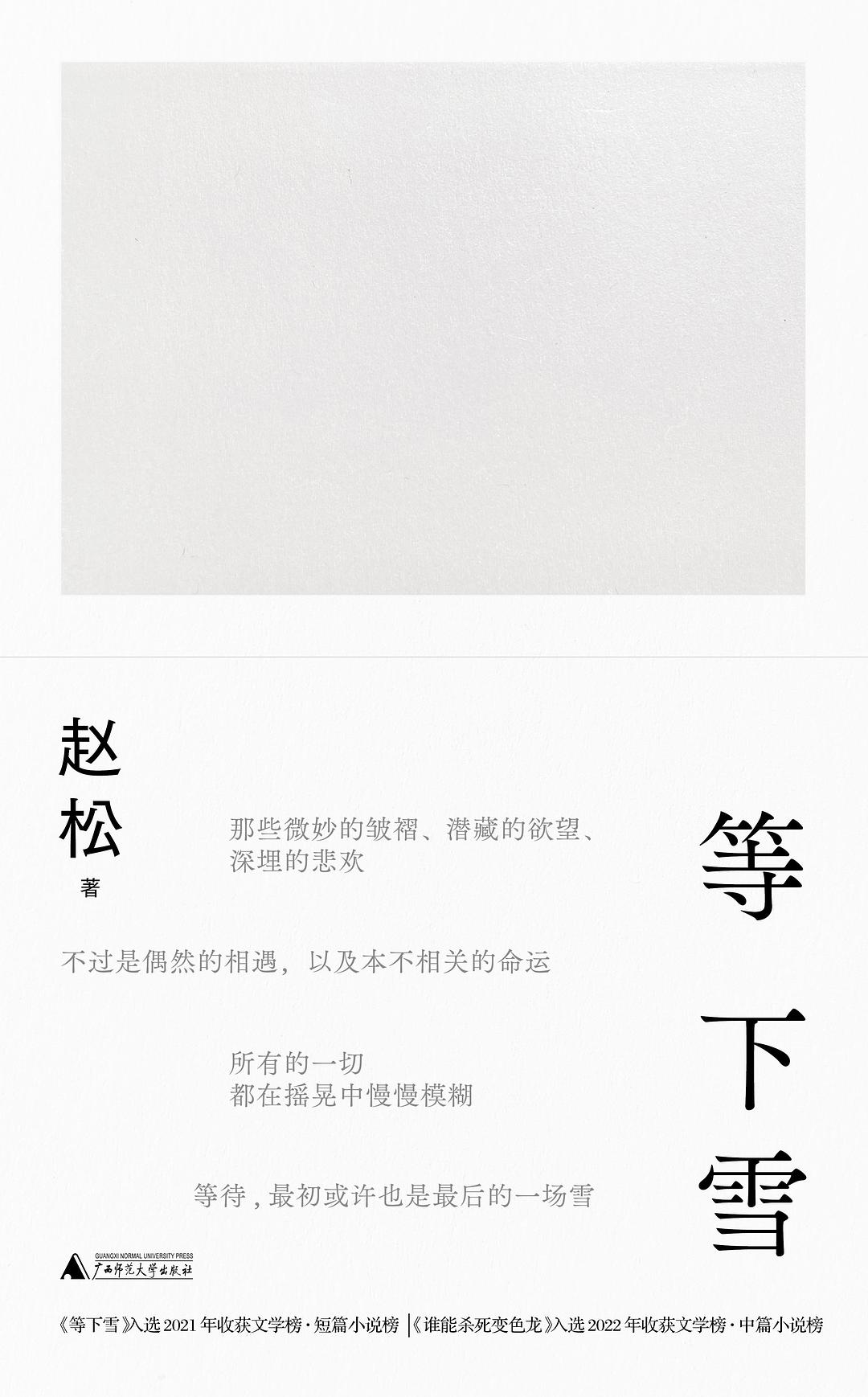

4. 赵松《等下雪》 (Waiting for Snow by Zhao Song)

Zhao Song is the oldest author on my top ten, and although it’s only by a few years, his fiction feels old-school experimental in the best way. Last time I sang his praises, I wrote that his fiction reminds me of Paul Simon: you might not understand the lyrics, but you feel their warmth and you feel what they’re supposed to mean.《葬礼》 “Funeral Rites,” one of the shortest stories in this collection, is the best encapsulation I’ve yet seen of how much Zhao can accomplish with how little. We know next to nothing about the old friends who meet up at the funeral of a former colleague, but there’s so much weight to their laconic conversation—one of them determined to dredge up the past, the other determined to leave it buried—that their history feels as complex as an unwritten novel.

3. 班宇《白象》 (White Elephant by Ban Yu)

What can I say? I’ve written extensively about why Ban Yu is one of my favorite authors, and in particularly one of my favorite prose stylists, in any language. He’s continuing to mature in his fourth collection, and the prizewinning centerpiece 《飞鸟与地下》 “The Bird and Underground” especially feels like a turn toward more introspective, mysterious, almost mystical writing. But my favorite piece here is 《白象》 “White Elephant,” because it’s classic Ban Yu. Give me dying fathers struggling to express their love to their sons, give me emotionally adrift young men having sudden epiphanies in bed with their bemused girlfriends, give me decades-old feuds resurfacing against the backdrop of postindustrial Shenyang. Nobody does it better than him.

2. 辽京《在苹果树上》 (On the Apple Tree by Liao Jing)

This quartet of linked short stories got unfairly overshadowed when, nearly simultaneous to its publication, the author’s earlier novel 《白露春分》Spring Will Never Fall won this year’s Blancpain-Imaginist Prize. Both books showcase Liao’s deft handling of the stifling ties and unspeakable resentments that can fester in close-knit families. But I think there’s a particular virtuosity to how she achieves this in On the Apple Tree, devoting one story each to the four members of a single household and their private agonies at various points in their lives. It’s an ingenious structure that, like Yu Hua’s Cries in the Drizzle and Aimee Bender’s The Particular Sadness of Lemon Cake, hits you with the unnerving realization that we never really know what’s going on in the minds of others, even our own family.

The stories stand alone but reframe each other when read together. This is especially true for 《我奶奶的故事及其他》 “My Grandmother’s Story and Others,” which ostensibly tells the story of the husband’s early manhood but is really about the forced silence of women in the shadow of men. Early in the story, the narrator depicts his grandmother’s death casually, in the middle of a sentence, as though it’s just a minor detail in the greater tale of his grandfather’s life. But this failure to recognize his grandmother’s subjectivity is the original sin that comes back to haunt him throughout the rest of the story, and, indirectly, the whole book. The most incisive deconstruction of the male point of view that I read all year.

1. 陈思安《穿行》 (Traversing by Chen Si’an)

I’ve never gotten to see one of Chen Si’an’s theatrical works—they’re widely acclaimed and have been performed all over Asia and in the UK—but, last month, I did get to enjoy her new novella collection in the best possible format: in a black-box theater in Beijing, dramatically recited by a group of professional actors. Chen’s characters are bursting with personality, practically begging a skillful actor (or reader) to come along and bring them to life.

There was no better testament to the sheer pleasure of reading fiction in the second half of this year than Traversing. Whereas the majority of young literary writers in China seem to value plot somewhat less than introspection and social commentary, Chen is in the business, above all, of telling a good story. Her plots are funny and heartfelt and bold all at once, whether they’re about a young man having an unexpected awakening courtesy of a sardonic drag queen (in 《歌杰斯》 “Gorgeous”) or a headstrong stage actress butting up against her director’s ego and the limitations of artistic expression in China (in 《穿行》 “Traversing”). Leave it to a playwright to concoct the best characters and dialogue of the year.

My top ten Chinese fiction collections of 2025:

- 张天翼《人鱼之间》 (Beyond Truth and Tales by Zhang Tianyi)

- 杜梨《漪》 (The Ripple of Shattered Cuckoo by Du Li)

- 陈思安《穿行》 (Traversing by Chen Si’an)

- 辽京《在苹果树上》 (On the Apple Tree by Liao Jing)

- 班宇《白象》 (White Elephant by Ban Yu)

- 郭爽《肯定的火》 (Undeniable Fire by Guo Shuang)

- 赵松《等下雪》 (Waiting for Snow by Zhao Song)

- 默音《她的生活》 (Her Life by Mo Yin)

- 李唐《神的游戏》 (Godly Games by Li Tang)

- 彭剑斌《欣泣集》(Laughter and Tears by Peng Jianbin)

Thanks for sticking with this newsletter through 2025. I have a lot of plans for the next few months of this newsletter, including author interviews, guest posts, and a rather ambitious finale to my 13 Ways of Looking at Chinese Internet Fiction series. So stay tuned, share widely, and subscribe on Substack if you wish. Wishing you a peaceful start to the new year.

Rules of this reading project: I sampled nearly every new fiction collection in China (jumping from piece to piece, not reading front to back). Reluctantly, I had to exclude a small handful of collections, maybe five or six, that I couldn’t get my hands on in time for this post. There was also a somewhat larger handful of works that I allowed myself to skip either because they received a limited print run and were mostly ignored by Chinese readers, or because they received overwhelmingly negative reviews upon release. I feel pretty justified in not reading those, although it might be fun to revisit the latter category someday.

Comments

There are no comments yet.